The Saudi parable

For the feminists (this is how they described themselves) whom I met in Saudi Arabia, the terrible war in neighbouring Yemen was not a pressing issue. They were primarily concerned with liberating themselves and other women from the shackles of an absurd guardianship system, in which a female human being remains the ward of a man for her entire life.

In these endeavours, apart from on their own power, the pioneers are pinning their hopes on the very man who could be held responsible for numerous war crimes in the Yemen war: Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, Defence Minister and Saudi Arabia's young strongman.

In globalised political jargon, the 32-year-old designated heir to the throne is described as a reformer – a situation that above all shows how little this term actually means. The commonly held view is that in nations outside of Europe – and in particular Islamic countries – there is a kind of package labelled with the R-word that routinely contains the following: more rights for women and minorities, market liberalism, readiness to co-operate with the West. If this package is unwrapped, this is called modernisation. But, as we are aware, the modern age is our invention and these reforms inevitably make Islamic nations more like us, the West.

A modern age to be feared?

So much for the fallacy. In actual fact, in the 21st century, each and every country is developing its own modern era; Saudi Arabia, in particular, serves as a parable in this regard. We don't yet know if Mohammed bin Salman's version of the modern age should be mostly feared.

What has happened in recent months under his direct or indirect influence can be divided up into three categories. Firstly: women should contribute more to the national economy; their driving ban has been lifted and the ominous ward system restricted to the extent that it does not prevent women from working. Secondly: the Prince wants all the power; competitors are neutralised, opponents arrested. Thirdly: his foreign policies are provocative and nationalistic.

And while long-serving female Saudi activists had tears in their eyes as they heard about the lifting of the driving ban, the humanitarian catastrophe in Yemen ran its course – a formulation that one has to choose when famine, suffering and cholera are being registered only by those aid organisations that have for months been calling in vain for a new political initiative to end the war.

Women and autocrats

It is not such a novelty to find women's rights together with repression and even torture on a political menu. Just think for example of the autocrat Ben Ali in Tunisia, where a so-called state feminism emerged.

Mubarak also loved women, Bashar Assad no less so, while the Shah of Iran cultivated a small educated female elite whose job it was to shine. Some women's rights activists allowed themselves to be corrupted, closing their eyes to the crimes of a nation to which they owed their own ascent. In Tunisia, the effects of this are felt to this day.

So that there are no misunderstandings: every centimetre of freedom gained for Saudi women is a good thing. But the fact that the Crown Prince is both forcing back the power of a misogynist clergy and is credited with speaking the language of the youth, should not detract from other issues. What we are seeing is the rapid growth of an aggressive young ruler in a Kingdom where there is already barely anyone able to stop him in his tracks.

Saudi Arabia's bond with the West has for decades been rewarded with chronically euphemistic media coverage. In times gone by, journalists reporting on tank acquisitions in Riyadh would find a gold Rolex on their bedside table as a sweetener. How long did it take before the public hesitantly realised that our strategic partner practices the least cultural form of Islam in the world? And does not allow a single little church for its exploited Christian migrant workers?

Recently, every report on Saudi Arabia′s erratic foreign policy seems to end up concluding that the Kingdom is simply battling it out with Iran for dominance of the region. All this does is wrap the incomprehensible in pseudo-plausibility.

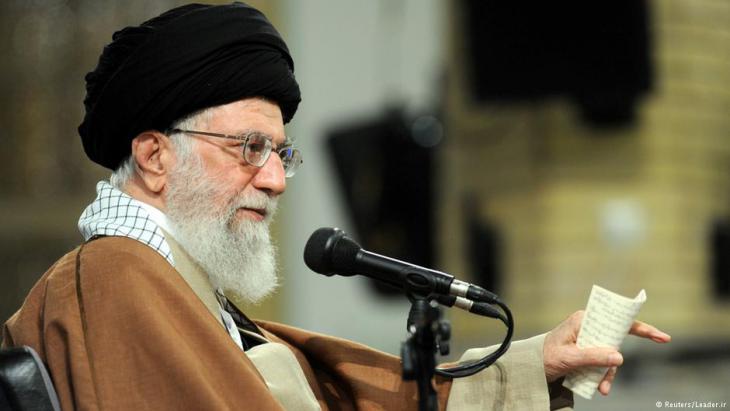

Germany paid astonishingly little attention when Mohammed bin Salman recently called Iran's Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei a ″new Hitler″. For which echo chamber was that comment intended? Not for the Arab street, a place where (unfortunately) too many people still hold Hitler in high regard. The Prince was aiming it much more at the West and to do this he used the language of Benjamin Netanyahu. The Israeli Prime Minister has frequently accused Iran of planning ″another Holocaust″.

No appeasement for Iran

It is indeed the case that in the power games of the Middle East, Israel and Saudi Arabia are presently closing ranks. The Saudis don't recognise the State of Israel? That doesn't matter. If Iran's Supreme Leader is the new Hitler, then there can be no appeasement in dealings with him. It could almost be one of Trump's tweets.

Writing in the Tehran Times, the Iranian journalist Mohamed Hashemi claimed the Saudi Prince might have been inspired by a German to make his Hitler comparison: the jurist and political theorist Carl Schmitt. Schmitt's idea that a sovereign can define a state of emergency himself in order to then derive the legitimacy of dictatorial emergency powers, is also motivating Mohammed bin Salman, says Hashemi.

If you continue spinning out these ideas, then it might also make sense that of all countries, Saudi Arabia now wants to position itself at the helm of the battle against Islamist terror. After all, there's now a new military alliance headquartered in Riyadh; another instrument of power for the Prince.

Another possibility would be to call on all those scholarship holders, Muslims from many nations who learned extreme ideas in Saudi Arabia, to attend a big detox workshop in Mecca… but don't hold your breath.

Charlotte Wiedemann

© Qantara.de 2018

Translated from the German by Nina Coon