The breakdown of Egypt's legal system

Mass death sentences now appear to be part and parcel of the sad reality of Egyptian jurisdiction. After a trial lasting just two days, and practically without the admission of any evidence, an Egyptian judge on Monday, 28 April 2014 sentenced 683 people to death in Minya. Among the convicted was Mohammed Badie, the spiritual leader of the Muslim Brotherhood.

One month earlier, the same judge recommended the death penalty for 529 members of the Muslim Brotherhood in a different mass fast-track trial, although he later confirmed just 37 of the sentences passed in March and commuted the remainder to life terms.

At both trials, the defendants were found guilty of attacking police officers, inciting violence and causing damage to public and private property. Both cases dealt with a mob attack on police stations in southern Upper Egypt on the day when the police and the military brutally broke up protest camps set up by the Muslim Brotherhood and opponents of the coup in Cairo.

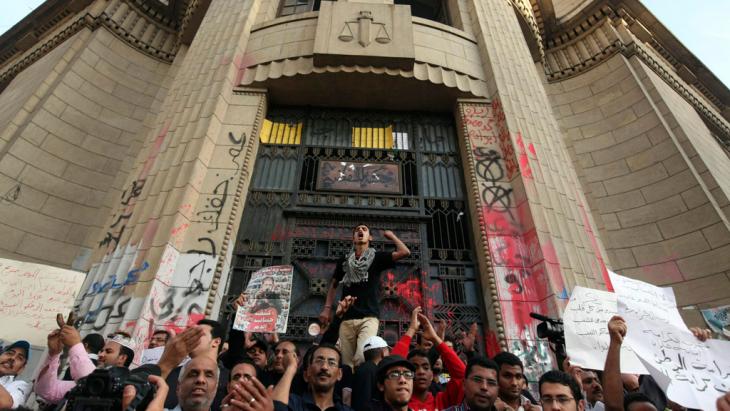

Lasting damage to the judiciary's image

On the same day (28 April 2014), a separate Egyptian court banned the secular 6 April youth movement, a group of young Tahrir Square activists who were heavily involved in the overthrow of Hosni Mubarak. The organisation was accused of conducting espionage activities and tarnishing Egypt's image. But at the end of this particular Monday, it was undoubtedly the image of the Egyptian judiciary that had suffered the most severe damage.

In view of the double standards employed by the Egyptian judiciary in these cases, the state prosecutors and judges are the ones who should really be in the dock. After all, while 529 suspected members of the Muslim Brotherhood were branded as terrorists and sentenced to death in one fell swoop at the initial trial, no court has to date addressed the bloody dispersal of protest camps set up by the Muslim Brotherhood and coup opponents by the police and the army, acts which triggered the violent clashes in Upper Egypt. Official figures put the number of people killed in last summer's violence at 623, other reports claim the death toll was more than 1,000.

As far as the 840 Egyptians who lost their lives during the uprising against the Mubarak dictatorship are concerned, hardly anyone has thus far been called to account via legal channels. Just three low-ranking police officers received trifling punishments; 183 other police officers were acquitted. The trial against Mubarak himself and his former interior minister has now been running for three years. "The Pharaoh", as Mubarak is known, was originally sentenced to life in prison, but proceedings were restarted and are still continue.

The judiciary as an accessory to the regime?

At the other end of the scale, the ban on the secular Tahrir activists of the 6 April movement was imposed from one day to the next. Even journalists have been dragged before the courts, accused of supporting a terrorist organisation because of their contacts with the Muslim Brotherhood.

Following the latest violent clashes at universities, students are also being sent to prison for up to 17 years. Last November, 21 young women from Alexandria, among them seven minors, were given prison sentences of up to 11 years for taking part in a demonstration supporting Mohammed Morsi, who was ousted from office by the military.

Even though some of the rulings against members of the Muslim Brotherhood and opponents of the coup have been moderated during appeal proceedings and even though the same can be expected at the next stage of the appeal process for the latest death sentences to be handed down, the damage to the image of the Egyptian judiciary will be huge if it is seen to be utilising the lower courts to send out political messages before something akin to a sound trial based on the rule of law begins when the case passes to the appeal court.

It would indeed be too simple to believe that Egyptian judges are receiving a call from on high dictating the judgements they are to hand down. Even back in the Mubarak era, the dynamic between regime and judiciary was far more complex than that. The regime was always able to fill key positions such as that of the most senior judge at the Constitutional Court or the chief state prosecutor, but every now and then, the odd judge issued rulings that were not at all to the taste of the regime and often went against the Muslim Brotherhood.

Parallel justice

Sometimes they would even issue an acquittal because the defendants' confessions had been elicited through torture and were therefore inadmissible in court. The "unreliability" of the judges was one of the reasons why the Mubarak regime increased the jurisdiction of the military courts operating in parallel to that of the civilian courts, as a way of getting the rulings it wanted.

In 2006, reformist judges even took to the streets to protest against large-scale electoral fraud that they had been required to invigilate. Five years before the revolution, it was they, the judges, who formed the vanguard of the protests against the regime. But most judges at the time resigned themselves to handing down judgements – some just, some not – in an autocratic environment, hoping all the while that they would not ruffle the feathers of the powers that be.

After the ousting of Mubarak, the judiciary remained untouched. Proceedings against representatives of the old regime were only begun very hesitantly, if at all. This was not only the fault of the judges; Mubarak's most senior state prosecutor initially remained in office, and the Interior Ministry proved itself to be a refuge of the old regime by showing little motivation to carry out investigations and hear evidence as it should.

The direct confrontation came during the tenure of President Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood. Morsi accused the judiciary of being a remnant of the Mubarak regime. The judges' response was to reproach Morsi for wanting to control the judiciary and occupy posts with representatives allied to the Muslim Brotherhood. The Constitutional Court then used a legal technicality to dissolve the elected parliament in which the Muslim Brotherhood made up the majority. The brotherhood spoke of a judiciary coup. At the time, they did not suspect that a real military coup would follow.

Heading for a confrontation with the Muslim Brotherhood

The final break came in November 2012, when Morsi issued a presidential decree affording his decisions immunity from jurisdiction. It was at that point that the judges finally took to the barricades. From then on, the judiciary was one of the key institutions that actively pursued the overthrow of Morsi. But there was some resistance to the military too: 75 judges who publicly declared that Morsi had been illegally removed from office were suspended from the professional federation. They were subjected to a disciplinary hearing and accused of illegal political activity, a rule that did not, of course, apply to the judges who had publicly supported the coup.

In the country's new constitution, the judiciary is now a closed shop: if one judge retires from the constitutional court, his colleagues are allowed to elect a successor. The judges elect the chief prosecutor, and the judiciary must approve new laws to regulate the legal system before they can be presented to parliament.

What looks like perfect autonomy for the judiciary does in fact conceal the danger that the Egyptian legal system could remain completely isolated from social and political processes; as a separate caste that never has to reinvent itself, it has effectively blocked any future attempts to reform it from the outside.

Instead of reforming itself, the Egyptian judiciary is compromising itself by assuming the role of an angel of vengeance against the Muslim Brotherhood. In doing so, the judges do not really regard themselves as an accessory to a regime; it is much more a case of them believing that they have to act as a sort of defender of the state, which they perceive to be threatened by a kind of "international Muslim Brotherhood conspiracy", in accordance with the smear campaign currently running in the Egyptian media and which is deliberately aimed at stoking a "them or us" stance.

Egypt's judiciary has positioned itself clearly on one side, although it should really have served as a neutral dispenser of justice especially now, in such a politically polarised climate. This would have been the perfect test case, an opportunity for the judiciary to demonstrate its professionalism and independence through processes based on the rule of law. But instead, not only is Egypt's Lady Justice doling out merciless rulings, she has also failed dismally. The breakdown of the country's legal system is a disaster that will eventually cost all Egyptians dear.

Karim El-Gawhary

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de