It's the economy, stupid!

On 1 January 2018 – the fifth day of protests in Iran – President Rouhani decided to follow the lead of his countryʹs security and military officials. While speaking of the importance of attention to economic and political realities and the peopleʹs right to protest, Rouhani overlooked the true reality of the situation, proclaiming: "There is a minority, a tiny group, who are seeking to come in and cause trouble: chanting slogans against the law and the will of the people, insulting the sanctities and values of the revolution and destroying public property. We will ensure they are rounded up."

There is no doubt that government – any government - is always engaged in "rounding up". It is in the essential working of government to round up collective wealth, to gather subjects and to stockpile power. At times, such an act takes on a harsher form. Banks and prisons, two important institutions in the modern Iranian order, are crystallisations of the ultimate form of this rounding up. These two entities may help us understand what has taken place in Iran in the last few months.

At the end of its rope

Since the moment privatisation and the economy of an "eastern" neoliberalism was rolled out in Iran during the administration of Hashemi Rafsanjani (1989-1997) through its ripening in the Rouhani years, they have, beside their other results, created a class of poor and destitute people who have viewed their own meagre prospects as being bound to the very government which in fact saps their lifeblood. Owing to their dependence on government aid, these people have always been the greatest supporters of those in power.

Because of economic challenges posed by various administrationsʹ adjustment policies and international sanctions, this burgeoning class has widened to include the classical middle class and is now at the end of its rope, in just the fashion Fyodor Dostoevsky describes in his Notes from the Underground.

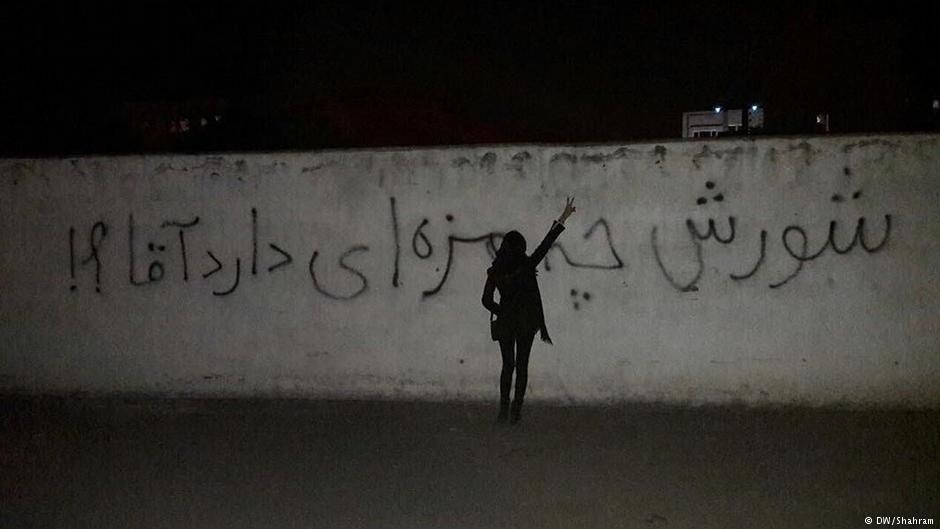

It should come as no surprise that this class tends to see itself as opposed to all the factions of Iranʹs two-party system (conservatives and reformists). In fact, it is the very thing the system in power has not been able to accomplish – unifying the government – that masses of protesters are doing now. This time around, protesters chant against all factions and cliques: reformists, conservatives, middle classes and the whole governing class have been called into question.

If this broad class was previously less inclined to join political, social and labour movements given its vital dependence on various administrations, it is now, in the course of this unexpected event, in the process of slipping out from Big Brotherʹs lap. More specifically, the possibility has been opened up by political scuffles within the ruling bloc. Conservative tendencies and those opposed to Rouhani who dreamed of using this classʹ grievances to their own ends, thought they could tilt the electoral field in their favour for the coming decisive presidential election by firing up the cauldron of economic woes as Ahmadinejad had. Now the cauldronʹs lid has flown off and political figures on all sides find their faces scorched.

Diffuse sense of nostalgia

This boiling cauldron is the outcome of the policies which govern the Iranian economy. This situation is not limited to Iran, but rather a global condition. Capitalism has fallen into a crisis of neoliberalism and its political consequences. The Rouhani administration is no longer keen to join global labour markets, for such a move would bring repercussions that they would prefer avoiding.

Even the reactionary demands some protesters have voiced in recent days (e.g. slogans calling for a return of the dictatorships of Mohammad Reza Pahlavi and his father) are in fact the Iranian form of a longing to return to the past, a sentiment brought about by discontent with the present situation, whose expressions we see elsewhere also as in Brexit and Trump.

What is moderation?

The moment he threw his hat into the ring for the presidency, Rouhani presented himself as heir to the legacy of Hashemi Rafsanjani and christened himself a moderate with neoliberal economic policies. In such a situation of moderation, nothing in fact remains moderate: in order to construct a moderate position, things must be done away with, voices silenced.A number of Rouhaniʹs policies are carried out in the name of moderation and adjustment: changes in labour law, bank loan conditions and housing programmes; the employment plan; the introduction of tuition at universities and remaking of curricula. But they are in fact brimming with radicalism, a plot to conserve and entrench class divides.

A controlled parliamentary democracy along neoliberal lines is the preferred political mode of the age and the instrument of its advancement is a weakening of the role of the human sciences and a removal of all intellectuals – save for free-market economists – from the circle of major decision-making.

Given such conditions, what we see unfolding in the streets of Iranʹs smaller, poorer cities should come as no surprise. We read in Hobbes that if people are sufficiently scared, they will do anything. A kind of fear that works more strongly than anything else: a collective fear which manifests itself in situations of collapse. Poverty, corruption, earthquakes, a polluted environment and other calamities are stoking the fears of Iranian society.

The recent events are not at all unexpected, in fact. Iranʹs deprived classes have spoken of their fears long ago: in small street protests, in their demonstrations and occupations before the parliament, factories.

Of protesters and agitators

Various political and social movements in Iran have, as in other countries, been labelled "subversive protestors (or agitators)" intent on undermining public security through the destruction of public property and other disturbances. We should recall that the principal agitation and disturbance is in fact to be found at the level of our collective life. The true agitators are the mechanisms and actors who have, through their conduct and policies, thrown our common collective life into chaos, leaving it reeling: the powerful, leaders of the major economic and cultural monopolies, and all who have helped implement the economic programme of social immiseration.

The protests are the outcome of circumstance and nothing else, e.g., the meddling of a foreign enemy. The efforts of both wings of Iranian politics to justify their ignorance and fear of protestors with charges of "agitation" and working for a foreign power, will disillusion their last hope. "Reform" means being answerable to the current situation – not denying it.

Amin Bozorgian

© Open Democracy 2018