Egypt's political prisoners speak

One effect of mass incarceration is the widespread silencing of the detained. This silence is often followed by a general amnesia, as society forgets those who are imprisoned.

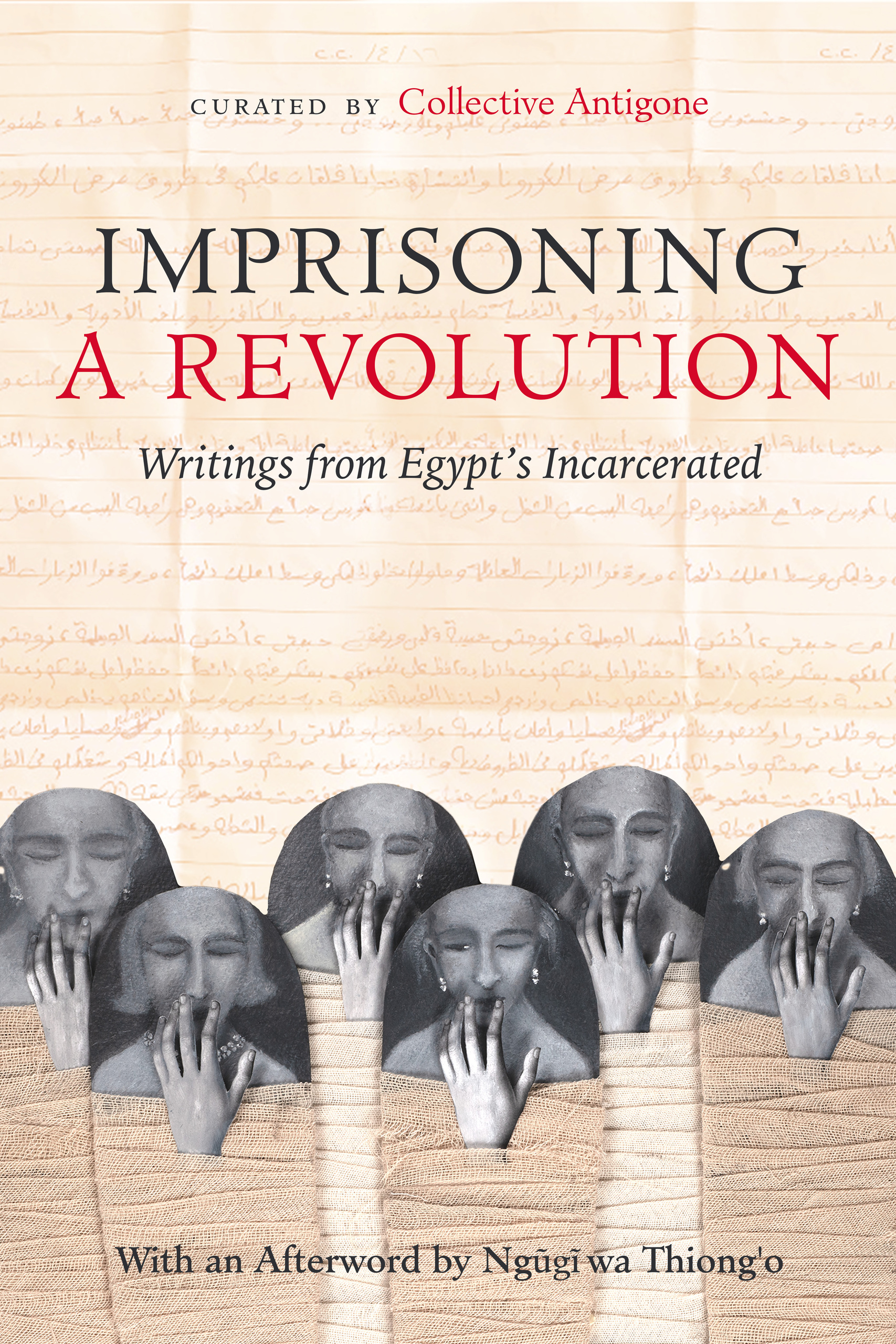

To fight this amnesia, the editors of "Imprisoning a Revolution: Writings from Egypt's Incarcerated" (2025), who call themselves the Antigone Collective, decided to create a space for the voices of more than a hundred Egyptian prisoners. "These prisoners include women and men; Copts, Muslims, and the non-religious; Islamists, leftists, and those with no defined political stance," they write.

In the introduction, the editors craft a new term to describe the Egyptian government—a "carceralocracy"—for its use of mass imprisonment as a key means of social control. The Egyptian people have been ruled by carceralocracy since 1914, the editors write, when the British imposed martial law.

This continued in the postcolonial period through the "emergency laws" that have been in near-continuous effect since 1958. And since 2013, they write, Egypt has experienced a spike in detentions "unlike any in its history."

"You have not yet been defeated"

Alaa Abd el-Fattah, arguably Egypt’s most prominent democracy activist, has just been handed another lengthy prison sentence. Despite this, a book of his writing has recently been published. It reveals the former Tahrir Square activist as a reflective, left-wing intellectual. Jannis Hagmann read the book

The anthology was conceived in conversation with Laila Soueif, mother of imprisoned writer Alaa Abd El-Fattah. Soueif—who is currently on a hunger strike in the UK to protest her son's detention—told the Antigone Collective that the most important thing they could do was to contest the enforced amnesia that surrounds Egyptian prisoners.

Soueif urged the collective to expand their advocacy beyond her son to prisoners across Egypt. Yet "Imprisoning a Revolution" is neither a series of testimonials nor a straightforward literature of witness. Instead, it is a collection of vibrant emotional landscapes that, the editors write, "compose a micro-history from below of contemporary Egyptian history from 2011 until 2023."

Selecting the voices

The Antigone Collective began by gathering prisoners' art, letters and literary works from a number of sources, including prisoners' family members, El-Nadeem Center Against Violence and Torture, The Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights, and various human rights lawyers. The number of letters they collected "quickly reached the thousands," editors said over email. From there, they worked to choose around 100.

Critically, they wanted to feature a diversity of viewpoints, ages, and a mix of men and women. "Within that framework we searched for literary quality—not necessarily or often sophistication or savoir faire," they wrote over email, "but an immediate getting at the truth of incarceration in one of the worst prison systems in the world."

Some are of the pieces written by prominent authors and poets who have spent time in Egypt's prisons: Alaa Abd El-Fattah, Ahmed Douma, Galal El-Behairy and Abdelrahman ElGendy.

Others are by activists well known in human-rights spheres, such as Sarah Hegazy, Sanaa Seif and Mahienour El-Massry. Some, like the photographer known as Shawkan, became well-known only after their arrest. But many of the authors are not known at all, and several remain anonymous.

The voices of the nameless

In his foreword to the collection, acclaimed author Ahmed Naji speaks to the importance of writing while imprisoned—not just for professional authors, but for others as well. Naji was sentenced to two years on a charge of "violating public modesty" after an excerpt of his novel "Using Life" allegedly gave a reader heart trouble. He ended up serving ten months.

Naji describes how one of his fellow prisoners, whom he calls Marcel Proust, documented his "lost time." Proust was neither a writer nor a political prisoner, but an employee involved in a corruption case. He was acquitted, Naji writes, after spending four years behind bars. During his release, the prison administration discovered his diaries, and they gave him a choice: burn them or forfeit his release.

Eventually, Naji writes, the man gave in and watched the flames "devour his lost time, tears running down his cheek, on his way to freedom." This unnamed man's memoirs survive only as a shadow—a text that no longer exists, as remembered by Naji.

The texts in the anthology span a range of forms. One moving section, curated by Mina Ibrahim, includes work by an unnamed Coptic prisoner who wrote his contribution in the margins of a Bible. The anonymous Copt was imprisoned after the Maspero massacre in October 2011, accused of causing "public agitation and disorder." Although he spent only four months in jail, he was unable to reintegrate into his community, so he left Egypt in 2017.

"How can I survive in a society based on hate?"

In 2017, Sarah Hegazy was arrested in Cairo for displaying a rainbow flag, the symbol for homosexuality and queerness, at a concert. The activist recently took her own life in Canada. By Christopher Resch

Each of the anonymous author's musings was written down beside a Bible verse, many of which reference prison. One imagines this man leafing through his Bible in search of any instance where someone is locked up—Jonah trapped inside the whale or Jesus locked in the governor's headquarters.

These writings were not intended as works of art, yet they allow us vivid insight. He writes: "The Egyptian prisoners seem more resistant to miracles than the Roman ones during the first days of Christianity. Is it because the Egyptian military allies with the Church? I do not know if Jesus is confused about whether I should be rescued and released like the apostles, or if the Egyptian security forces are more powerful than him."

We are not given any introduction to another author, who pens the horrifying, "Sounds of the Execution Chamber from the Room Next Door." This text, which is dated 4 September 2019, is from the archives of the El-Nadeem Centre.

"Those taken to their death are terrified by the time they get to the door of the gallows room," the unnamed prisoner writes, "and they rush to the closest door—the door of my room—asking to escape from death. Through the hole in the door, I have seen terror that I cannot describe."

Looking in, looking out

Not all of the book's contributions are written. Mahmoud Mohamed Abd el-Aziz, who renamed himself Yassin, shared the art he sketched and painted in prison. These artworks speak not only to what was there, but what wasn't. One work is a portrait of a woman, her eyes obscured, in three colors—blue, yellow and green—because he had only two tubes of color. And because he had no brushes, Yassin painted with his fingers.

One of Yassin's ink portraits is of an old man's back, as he sits on a chair and wears the uniform of administrative detention, the word "interrogation" written on his back. The strange blocky hallway contrasts with the man sitting awkwardly on a stool, facing away, a door tantalisingly open in the distance.

The anthology doesn't include any photos taken by the young photojournalist Mahmoud Abu Zeid, known as Shawkan, who was arrested for covering the Rabaa massacre on 14 August 2013. Shawkan remained in pre-trial detention until March 2016. When he appeared in the courtroom, he didn't have a camera with which to document events—instead, he was being documented.

But Shawkan used his hands to form the shapes of invisible cameras, and these photos of him, taking ghost-photos of the viewer, circulated around the world. The anthology reproduces four of the photos, taken by Moustapha El-Shemy and Heba el-Khouly, in which Shawkan insists on framing the world, in making meaning.

This re-framing is the essence of a varied, multi-genre anthology that allows prisoners not just to speak, but to set the terms of the conversation.

Innocence incarcerated

Mahmoud Abu Zeid, known as Shawkan, took some photographs at a Muslim Brotherhood demonstration. As a result he has spent almost four years in prison – without any verdict having been passed. By Karim El-Gawhary

Against carceralocracy, worldwide

Both the introduction and the foreword to "Imprisoning a Revolution" make note not just of mass imprisonment in Egypt, but of systems in Rwanda, El Salvador, Cuba, and the United States. The editors' introduction describes how the U.S. prison system became a new way to control the country's Black citizens after 1865. In his foreword, Naji discusses his experience judging a literary award for US prisoners.

The editors said, over email, that they didn't expect the anthology—or anything else—to pressure Egypt to end its carceralocracy any time soon. What they intend is for "Imprisoning a Revolution" to inspire others to "continue the struggle—not just in Egypt but globally—against mass political imprisonment."

They write: "As the sudden revolutionary overthrow of the Assad regime has reminded us, the tide can turn at any moment, and long-silenced voices can suddenly be free to speak, cry or even scream their truths."

Imprisoning a Revolution: Writings from Egypt's Incarcerated

Collective Antigone

University of California Press

February 2025

© Qantara.de