Your philosophy, my religion

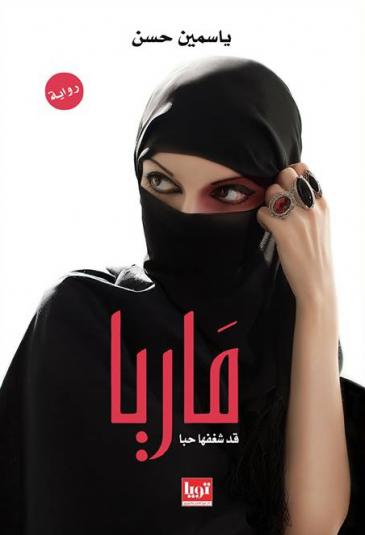

Jasmin Hassan was photographed while signing copies of her novel ″Maria″ at an event in the centre of Cairo. The resulting photo, which was later posted and shared on Facebook, unleashed a heated debate between supporters and opponents of a phenomenon that is still quite new in the Egyptian literary scene, namely that of the niqab-wearing writer.

Before 2011, Fadwa Hassan was the only author in this category, coming to the attention of the public with her debut offering, ″Fadwa″ in 2008. Since then, however, the number of niqab-wearing writers has risen to a dozen.

In the past three years alone, they have published 26 works, ranging from novels and short stories to collections of poetry. Most of them have a religious, Salafist slant. The titles of these works speak for themselves: ″The beautiful niqab-wearer″, ″The man with the black beard″, ″My beloved, the IS fighter″, ″And so she spoke to me″ and ″Behind the veil″.

The writer Dua' Abdurrahman has published no less than five novels, her most recent offering being ″And so she spoke to me″, which proved so popular that it was reprinted a total of 26 times within the space of only 12 months.

The author is opposed to the dogma held by some extremists that literature is apparently of no benefit to humankind. ″Most of the religious scholars I know are writers,″ says Dua' Abdurrahman. ″Indeed some of them helped me proofread my most recent novel. They are of the opinion that every area of life has its useful and less useful aspects.″

Literary experience gained online

Mona Salama had already published four novels in e-book form when her first novel appeared in print in 2015. Says Salama: ″The fact that I wear a niqab never caused me any problems, neither when I started writing nor later. I began by writing for the literary corner of an online forum for women. Then I wrote for fans of literature in Facebook groups. The only thing that should matter to my readers is what I write.″ She goes on to say that ″through our religion, we are familiar with the act of telling stories. So it is not really all that surprising that we write.″

Jasmin Hassan also began her career in online literary fora. However, unlike some of her colleagues who wear the niqab, she does not see her texts as being subject to the strict rules of Sharia. ″The niqab is generally equated with being forbidden to do something. I, by contrast, wanted to test my conviction that the wearing of a face-veil doesn't impact on the quality of a woman's writing.″

In the case of Shahanda Zayat, writing was the starting point for a career in publishing. She founded a publishing company and published two novels by niqab-wearing writers, both of which sold well at the most recent Cairo Book Fair.

Zayat wrote her first story (″She is the unknown one″) at the age of nine. It was about a young girl who lives in an ultra-conservative society and dreams of becoming a writer. ″I didn't just suddenly start writing out of the blue; it was the natural product of my intensive study of the works of Mostafa Saadeq Al-Rafe'ie, Mustafa Mahmoud, Anis Mansour and Abbas el-Aqqad,″ she explains.

Zayat says that as far as she is concerned, the wearing or otherwise of a niqab by the author does not tip the balance when deciding whether to publish her work; it is talent, she emphasises, not the choice of clothing or religious or political convictions that matter to the members of the selection committee.

Taking on the Muslim Brothers

For author and literary critic Huwaida Saleh, the emergence of niqab-wearing authors arose from the fact that when forming a government, the Muslim Brotherhood had great difficulty recruiting a suitable Minister of Culture from within the ranks of its leaders. Saleh says that when intellectuals subsequently rose up against the Muslim Brotherhood, organising a sit-in in the building that houses the Ministry of Culture, it was the beginning of the end of the government.

At the time, she continues, the brotherhood realised that it needed top-class intellectuals within its own ranks. This led to the phenomenon of the bearded and the niqab-wearing novelists and consequently, to the increasing publication of novels of a religious hue. Compared with religious sermons – whether in mosques, on television or on the Internet – the novel has proven to be the more effective medium.

According to Huwaida Saleh, given the widespread phenomenon of the so-called ″niqab writers″, it is legitimate to ask whether these writers do not have every right to write and express themselves. To this, she responds: ″having read a whole series of works by these 'niqab writers' and looked at them from an aesthetic perspective, I concluded that they have very little to offer artistically.″

Saleh is of the opinion that they neither bear the established and recognised hallmarks of the novel as a literary genre nor its aesthetics, ″in terms of the elements of neither the classic novel – such as plot, relationship between space and time, constellation of characters – nor the nouveau roman, which is characterised by its fragmentary style of narrative, its playful handling of time and the way it borrows from the aesthetics of other genres such as poetry, film and the visual arts.″

The spread of mediocrity?

Other readers could, of course, assert that this kind of moralising literature, which has made the interweaving of instructions and commandments in the writing its stylistic device, has always existed, even during in the era of Naguib Mahfouz. So what's all the fuss about?

To this, Saleh replies: ″the context is completely different. Back then, only a small number of copies of such works were printed. Today, the new media make it easy for people to bring all manner of banalities into circulation. Dozens and dozens of texts that are loftily referred to as novels can be printed. Faced with this phenomenon, the critic questions the artistic value and aesthetic awareness of these works. It is not a futile exercise to apply the standards of literary criticism to such texts. Indeed, it has to be done if we don't want mediocrity to just take hold.″

Hamdi Al-Nurg, professor of literary criticism and discourse analysis at the Egyptian Academy of Art, takes a more nuanced view: ″a whole range of aspects can be gleaned from the plurality and diversity of the literary discourse: the ideology articulated in it, its impact on the coining of phrases and the establishment of values, its vision of the essence of things, of the nature of art. A sober literary critique must address all of these immanent aspects of the discourse. With their diversity, perspectives, and content, discourses carry in them the seed of big ideas; ideas that have the potential to be realised, that trigger debates, and that can have an impact, as well as those that constitute a burden. In other words, it is not about denying the significance of ideas. Nor should we force discourses into rigid forms and preserve them artificially.″

Against this backdrop, Al-Nurg points to the fact that we are dealing in this context with discourses that are being fed by an identity defined by radical Islamism, whereby a definition such as this is based on formal, external, content-related, and intertextual classification criteria. He stresses that it is not important who says something, but what is said. As long as the discourse – whatever its form – develops out of societal dynamics, the issue of its acceptance is not a matter for the scholarly caste to which some critics or even artists aspire to belong, suddenly initiating discourses from the peace and quiet of their studies in the middle of the night, only to reject them again in the cold light of day.

Al-Nurg reaches the following conclusion: ″we are still caught in the same thought patterns as others before us and find it difficult to do justice to the phenomenon that is ′niqab literature′. How can it be that a genre such as the so-called ′erotic novel′ is greeted with lively enthusiasm while a serious form of women's writing that rejects modern trends is ignored by the field of literary studies?″

Sameh Fayez

© Qantara.de 2017

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan