A Well-staged Show

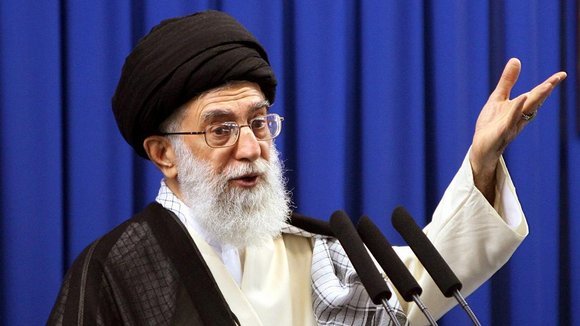

Iran's revolutionary leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, wanted the country's parliamentary elections to be a "slap in the face" for all his opponents. The man at the top of the Iranian regime will undoubtedly be satisfied with the results of the election, which he previously described as a "critical moment".

For the first time since Iran's controversial presidential elections in the summer of 2009, Iranians went to the polls to elect a new parliament on 2 March. Back then, protests against President Ahmadinejad's rigged election victory thrust the Islamic Republic into one of the most serious crises of its history. Only a violent crackdown made it possible for the regime to keep the Green movement, which was calling for free elections and civil rights, in check.

Urgently needed legitimization

At international level too, Iran is currently under enormous pressure as a result of its nuclear programme. The regime perceives international sanctions and the possibility of an Israeli military attack as immediate threats. For this reason, the Iranian leadership hoped that elections would run smoothly, thereby giving it an urgently needed boost in legitimacy.

First of all, it was important that enough people actually went to the polls, an outcome that could be portrayed as a demonstration of the people's support for the system. In recent weeks, representatives of the regime stated that they were aiming for a turnout of at least 60 percent. Strangely enough, the recently published official turnout figure of 64 percent is identical to the figure announced by the state-run media on the day of the election, thereby giving rise to speculation that the elections were once again rigged.

It must be said, however, that a non-negligible section of the population is still willing to go to the polls. Where possible, people whose livelihood depends on the state need the stamp of their polling station on their identity card. Moreover, people who live in the provinces often feel that the only way to push through their local interests is to elect people to represent them in parliament in Tehran. What's more, against the backdrop of international threats, it is likely that widespread patriotism moved some to cast their vote.

In prison or exiled

Nevertheless, the elections were strictly monitored by the police and security services. In order to prevent a renewed flare-up of protests, activists and critical journalists were arrested or put under pressure in the run-up to the election. The freedom of movement of foreign journalists was also severely restricted.

Followers of the Green movement had called on people to stay at home on the day of the election. Most reformist politicians are either in prison or in exile. They referred to the parliamentary elections as an "orchestrated farce", pointing to the fact that both opposition leaders, Mir Hossein Mousavi and Mehdi Karroubi, have been under house arrest for over a year now.

In February, Karroubi's wife announced on his behalf that he would be boycotting the elections. Mousavi also got family members to state that he had not changed his mind or his stance. These announcements resulted in a further increase in their isolation.

Former president Mohammad Khatami had made the release of political prisoners and a loosening of censorship a condition for an active involvement of the reformists in the election. The fact that he himself cast his vote caused bitter disappointment among supporters of the Green movement.

A struggle for power and resources

Quite apart from the importance of the elections for the regime's dispute with domestic and international opponents – an importance that was above all linked to the question of voter turnout – the elections were also a means of settling conflicts among the country's elite. Once the reformists had been moved off stage, this conflict was restricted to the conservative camp alone. It was less about fundamental ideological questions and more about access to power and resources.

Representatives of the traditional leadership elite failed in their attempts to bring unity to the "principlists" (those who are "faithful to the principles", as representatives of the conservative camp like to call themselves). In some cases, their candidates even refused to cooperate and sonsequently competed against each other, robbing their camp of votes.

On the basis of the votes counted so far, 190 of the 290 seats in parliament have been allocated. The remaining seats will be filled in a second round. A coalition led by the ultraconservative Ayatollah Mahdavi Kani was more successful than any other. Also on this list were the current and previous parliamentary speakers, Ali Larijani and Gholam-Ali Haddad Adel. Both men are close to the revolutionary leader and are now competing with each other for the post of parliamentary speaker.

A small proportion of votes was cast for the candidates supporting the notorious hardliner Ayatollah Mesbah Yazdi. These candidates partially agree with some of the positions of President Ahmadinejad, but are critical of his close advisor Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei, who indirectly called into question the predominance of the Shia clergy with his religious-nationalist discourse, thereby touching on a political taboo.

Ahmadinejad's supporters have obviously not been very successful. Some candidates that are closely allied with the government were already filtered out by the Guardian Council in the run-up to the elections. Others, including Ahmadinejad's sister, were not elected to parliament. However, it is said that the government put up a number of lesser known candidates in the provinces. Their actual political orientation will only become clear once they are in parliament.

Ahmadinejad's waning star

Ever since he openly challenged the revolutionary leader last year, Ahmadinejad's star has looked like it is on the wane. This challenge centred on the fact that the president wanted to push through his own candidate for the post of Information Minister against Khamenei's will. Khamenei reacted by putting Ahmadinejad in his place. Ahmadinejad is now in a similar situation to his predecessor, Khatami, whose power to make decisions in the Executive was increasingly restricted by Khamenei's manoeuvres.

In this way and more than anything else, the result of the parliamentary election confirms that the revolutionary leader holds all the strings of power in his hands. Complete and utter allegiance to Khamenei would appear to be the fundamental prerequisite for political success. In all likelihood, Khamenei will have command of a fractionalized parliament whose members will barely be able to arrive at a position that can command a majority without his intervention.

Khamenei will be able to keep his hot-headed president in line by threatening to summon him and have him removed from office by the parliament. Outgoing members of the Majles (parliament) had already advanced such a plan. However, because most of these government critics have been voted out of parliament, it is questionable whether Ahmadinejad will have to justify himself to them in March, as was planned. That being said, Khamenei could get the ball rolling on such initiatives whenever he chooses.

With the consolidation of Khamenei's rule, it is highly unlikely that there will be a change in Iran's political direction. However, it is difficult to see how this stage-managed election will improve the legitimacy of the regime. What's more, the incessant bickering among those who are loyal to the revolutionary leader calls the system's ability to act into question. The effects of the sanctions and mismanagement mean that people are becoming increasingly dissatisfied. There is no victory worth speaking of yet in Tehran.

Marcus Michaelsen

© Qantara.de 2012

Translated from the German by Aingeal Flanagan

Editors: Arian Fariborz, Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de