Romantic ideals for a new generation

In Katz’s adaptation, The Prophet: A Graphic Novel is still comprised of prose poems, depicting the musings of the exile Al Mustafa (the prophet) upon his return home from the island of Orphalese, and they remain intact, albeit in a different order.

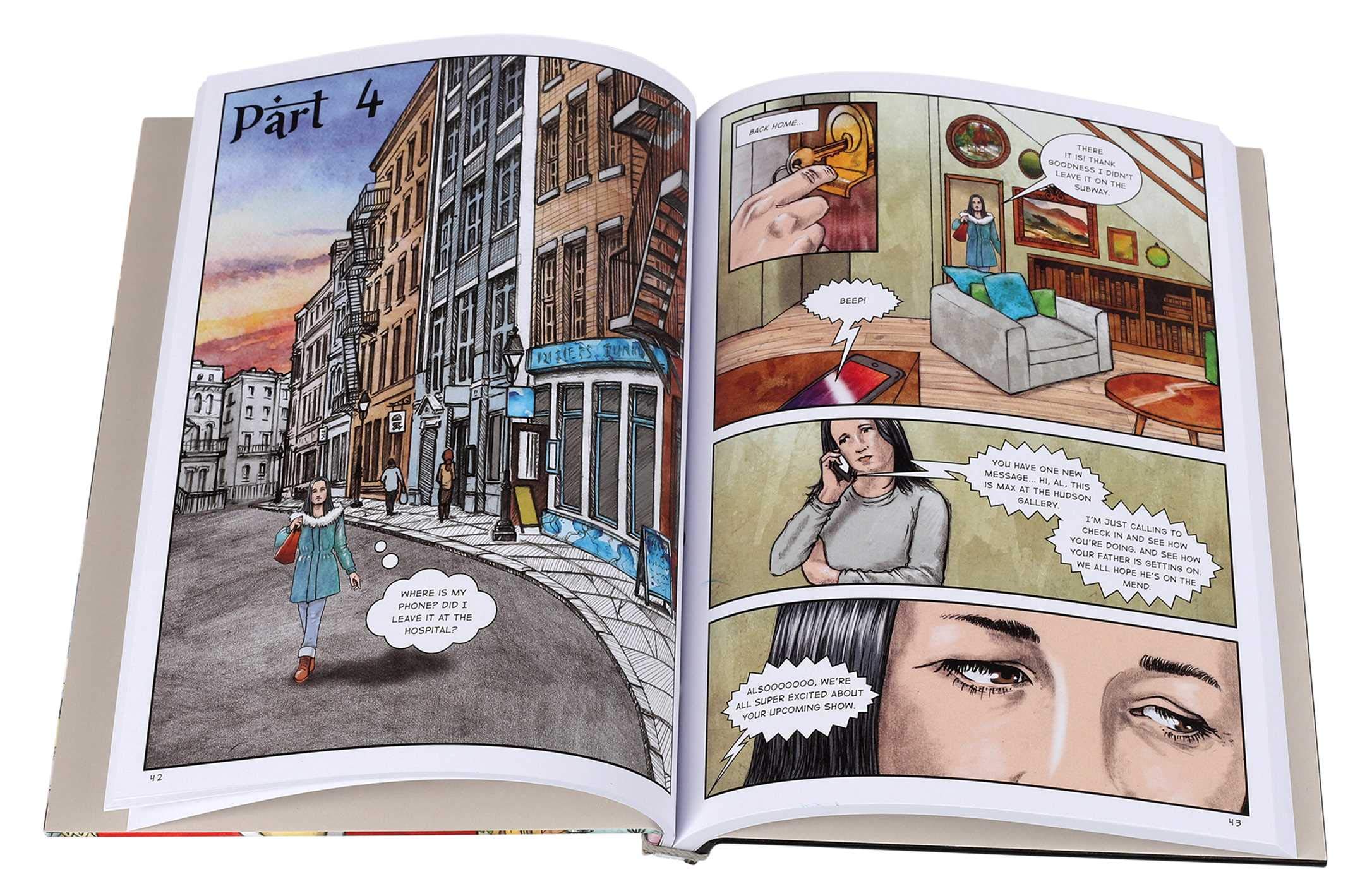

But around the prose poems, a more modern narrative emerges that reveals the timeless impact of The Prophet upon its readers: a modern-day artist, Al, contends with the hospitalisation of her ailing father with the help of a friend, the nurse Andrew, who gives Al a copy of the book hoping it will help her navigate a difficult period, as it did him.

Katz’s modern-day frame narrative with the artist Al and Gibran’s prose poems featuring the prophet Al Mustafa are interspersed throughout the graphic novel, allowing them to reflect thematically upon each other. As Al learns from reading the borrowed book, her own modern narrative – set mostly in the most central location of this COVID era, the hospital room – appears to reflect the pain, trauma, unmooring, self-reflection, and introspection expressed by the prophet Al Mustafa in his inspirational words of farewell to the crowd before he boards a ship back home. These original themes are also mirrored in the aesthetic created by Katz, with its romantic, dreamy, soft portraits.

"I knew your joy and your pain"

For students of Romanticism or of Gibran alone, Katz’s graphic novel, as with his previous illustrations and adaptations of classics such as The Art of War and Frankenstein, may well provide an entry into the literary-artistic movement and one of its most controversial figures – controversial in the sense of dividing the popular and the academic vote.

Indeed, Gibran’s sentimental, romantic prose poems probably appeared antiquated or even corny when they were first published. And yet, for students of the Romantics and Sentimentalists, the sentimentality of Gibran’s voice, though maligned by critics, is precisely what needs highlighting, since Gibran is credited with reviving the movement’s literary style with The Prophet.

Moreover, it has been said that the prophet Al Mustafa reveals Gibran’s Romantic understanding of the function of the poet, in his ability as teacher and visionary to intuitively grasp and express what people have difficulty putting into words. As Al Mustafa tells the crowd gathered around him:

"I knew your joy and your pain, and in your sleep your dreams were my dreams … I mirrored the summits in you and the bending slopes, and even the passing flocks of your thoughts and desires …."

The dual roles of poet and prophet are likewise expressed by Emerson: "The sign and credentials of the poet are that he announces that which no man foretold … he is the only teller of news, for he was privy and present to the appearance which he describes."

While Al Mustafa is asked to reveal truths about love, friendship, labour and suffering to the crowds upon his departure, he obliges without elevating or distinguishing himself from those around him. A Romantic humanism that appears to be at service of the people, rather than in opposition to them or in derision of them, informs the voice of the prophet. And likewise, Katz’s dreamy, soft portraits of Al Mustafa and the crowds linger on their expressive faces and kind, crinkly eyes, highlighting the goodwill he has established.

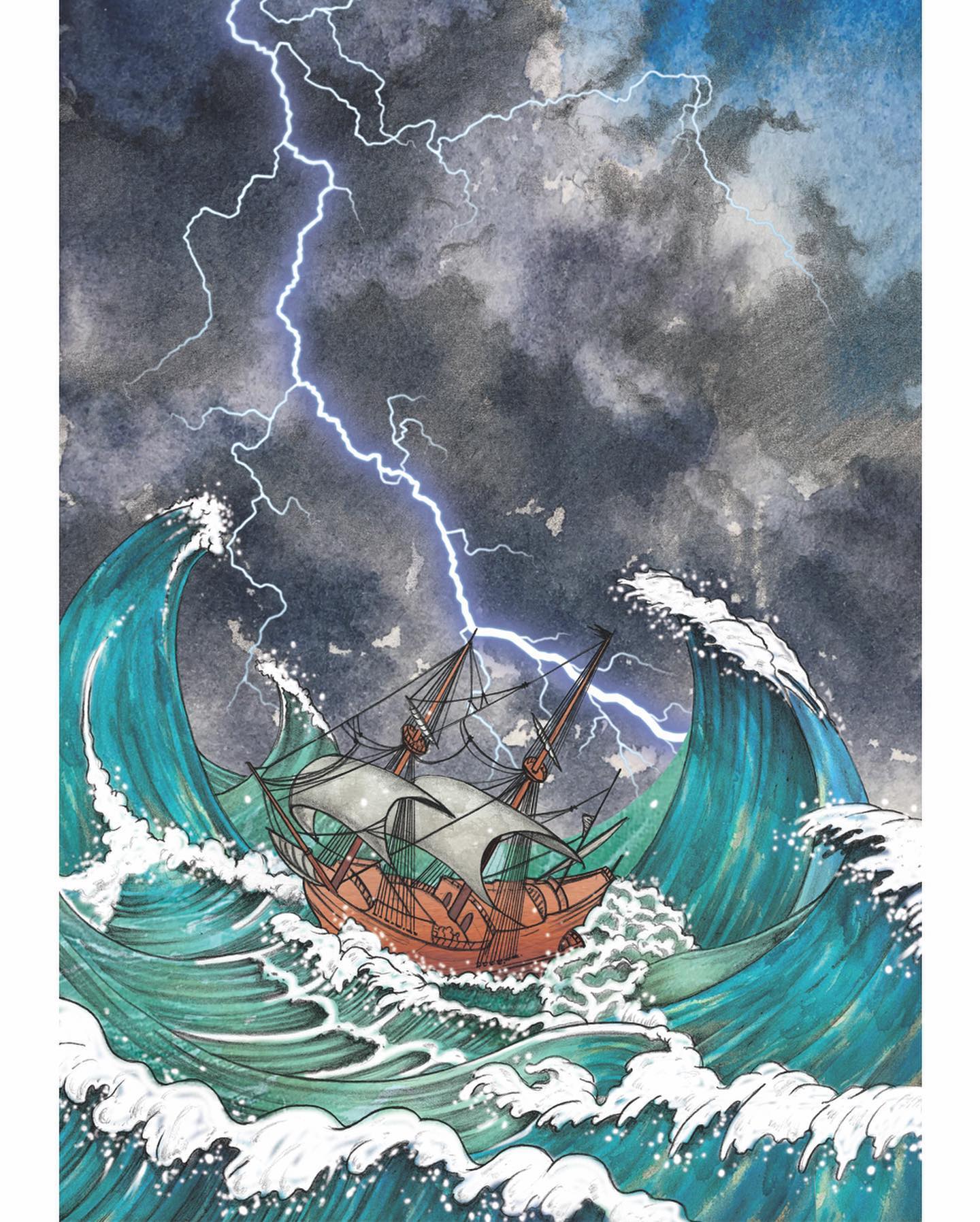

The relationship between the individual and nature is depicted in panels that surrealistically join humans, flora, and fauna all together to form a pattern of arabesques. The prophet’s metaphor of seafaring as a soulful navigation of adversity is illustrated in two panels, one a stable sea cradling a ship and the other a tumultuous sea threatening to capsize it, emphasising the relationship between the interiority of man and his natural surroundings.

Indeed, Katz’s detailed, vibrant illustrations gesture toward the Romantic ideals of the unity of man and nature. But they also reveal a division, as other interlocking patterns can be found slicing a starry sky in two, or foregrounding elements of nature – animals, plants, grains – against a backdrop of the site of their instrumentalization: a kitchen, an oven, a table set for a meal.

Re-framing the timeless

Katz's update to Gibran’s The Prophet within a modern frame narrative has not escaped the Romantic ideals of Gibran’s work: certainly, the contemporaneity of the central site of Al’s grief, the hospital, rendered in muted tones and clean lines, jars against the framed narrative’s vibrant, lush backdrops curving around interlocking arabesques.

Yet the impact of the framed narrative upon the frame is timeless: the connections Al Mustafa aims to sustain with others, with his surroundings, in a deeply humanistic voice ("And your heartbeats were in my heart, and your breath was upon my face, and I knew you all") drive a despondent, unmoored Al to reconnect with her community in an effort to navigate through her grief.

It is no wonder that Katz dedicates his book to "the courageous medical professionals and key workers who battle on the front lines against the coronavirus all over the world on humanity’s behalf." Considering the hospital room as our era’s central site of trauma, the timeliness of the modern tale perhaps pivots on an understanding of community as making survival possible.

As the prophet tells the crowd, "Like a giant oak tree covered with apple blossoms is the vast man in you. His might binds you to the earth, his fragrance lifts you into space, and in his durability you are deathless."

Nahrain Al-Mousawi

© Qantara.de 2020