Forget the people

It has become commonplace to hear questions such as: why do people comply with authoritarian exploitation? Why don′t they rebel, reform or change the status quo? Wouldn′t they like to live in a democratic system?

Most people, in fact, do yearn for the end of authoritarian exploitation, but they lack the collective organisation to do achieve it. Thus, the answer is more related to organisational issues than people′s aspirations. People are organisationally outmanoeuvred by ruling elites. Any rebellion against authoritarianism is more likely to serve the dictator than the population.

Case in point – Egypt

Let′s take Egypt as an example: following independence, the people in Egypt were subjected to authoritarian rule, controlled by military, police and political elites at the top (otherwise known as the ruling blocs). For over 60 years the masses complied because they lacked the collective organisation to do otherwise.

Any involvement of people in decision-making processes meant a loss of power to the regime in control. Therefore, the regime under Nasser, Sadat, Mubarak and – most notably – al-Sisi created structures to guarantee their survival. The organisation and reorganisation of ideological, political, economic and military networks was enforced through coercion and imposition, even if some (mostly incapable of making fundamental change) rebelled and resisted.

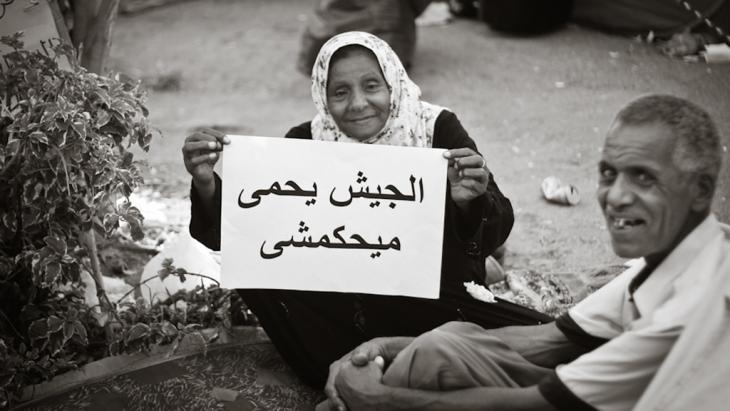

However, by 2011, the collective incapacity to change the status quo in Egypt was galvanised into collective action, resulting in mass protests on a huge scale. While these dynamics are dialectical and intertwined, a division of labour among the elites of the ruling blocs occurred in an attempt to counterbalance the collective action of the public.

After the fall of Mubarak, this collective action produced new elites, such as the Muslim brothers and the Salafist parties, which duly shared the power between themselves. As a result of the power struggle between these political adversaries, the regime – i.e. the military and police forces – was forced to outflank the organisation of rival actors to remain in power.

Comprehensive monitoring

Subsequently, the Muslim Brotherhood was banned, while the Salafist parties were generally co-opted. This process was characterised by a mix of conflict and co-operation, thus ensuring that the actors′ conflicting interests and goals had an impact on both legislation and social norms.

This shift towards the institutionalisation of society gave the ruling blocs absolute freedom when it came to monitoring the population and reorganising their own power networks, repressing the people as they did so. This meant that any dissenters outside the institutionalised social realm were now illegitimate and able to be outflanked with force.

This is most apparent when we consider the crackdown against the Muslim Brotherhood and their demonstrations against the military coup in 2013. Under the interim President Adli Mansour, the coup elite passed new protest legislation. Act 107, which was passed on 24 November 2013, gave the interior ministry the right to cancel, postpone or relocate any demonstration if there was intelligence to suggest that the protestors might break the law. This law emerged from the implementation of the Constitutional Declaration issued on 8 July 2013, only five days after the deposal of the Islamist President Mohammed Morsi.

Between repression and co-operation

There would appear to be two power structures at play here. The power exerted over the population by imposition and coercion – that of co-ordination. And the power achieved through people sharing a collective understanding – that of co-operation.

Due to the fact there has not been an elected parliament in Egypt since 2013, al-Sisi enjoys the privilege of passing laws in the form of decrees, imposing his will despite popular resistance. The people are thus denied any participation.

Hisham Barakat, Egypt′s attorney general, was assassinated in a car bomb on 29 June 2015. He was the architect behind the mass prosecutions (including controversial death sentences) of Muslim Brotherhood followers. His death gave al-Sisi an excuse to boost his involvement in communication and interaction networks, thus granting him even more organisational superiority over the Egyptian people.

At Barakat′s funeral, President al-Sisi promised to amend the laws to make them responsive to the implementation of justice. ″Under such circumstances, courts are useless and so are laws … The arm of justice is chained by the law,″ said Al-Sisi promising to carry out any death or lifetime sentences against what he called ″terrorists″.

All power to the dictator

Consolidating his distributive power faster than any other Middle Eastern dictator to impose his decisions on the Egyptian population and territory, al-Sisi co-opted the judicial system as well as the communication networks. Al-Sisi now has both the means of persuasion (institutionalised means) – the law, government loyal clergy and media – and the means of coercion – military, police and security forces – at his disposal.

Thus, people comply because they have neither the means nor the wherewithal to change existing power networks and organisations. They are embedded in organisational power structures, which they don′t control. Bypassed and weakened by those at the top, they are in no position to achieve any kind of noticeable change.

Nor is this pattern solely confined to Egypt: it applies to all of the Middle East and North Africa. Syrians, Yemenis and Libyans are all suffering as a result of current political developments. All too often revolutions do not serve people′s aspirations. It seems it is impossible to transform political impotence into collective agenda-setting power.

Hakim Khatib

© Qantara.de 2016

Hakim Khatib is a political scientist and works as a lecturer for politics and culture of the Middle East, intercultural communication and journalism at Fulda and Darmstadt Universities of Applied Sciences and Phillips University Marburg. Hakim is a PhD candidate in political science on political instrumentalisation of Islam in the Middle East and its implications on political development at the University of Duisburg-Essen and the editor-in-chief of the Mashreq Politics and Culture Journal (MPC Journal).