Negotiating with jihadists?

To neutralise; to render harmless. When it comes to killing Muslim terrorists, people could just as easily be talking about pest control. The impression is that the perpetrators are beyond all generally prevailing standards and that as a result, international law does not need to be applied in efforts to eradicate them.

The War on Terror, waged in precisely such an unfettered manner on both a psychological and legal level, has failed militarily on most fronts. This also weakens the interpretive power of the Western definition of the absolute enemy. From the point of view of populations in Africa and Asia, jihadists – who frequently present themselves in the garb that their religion demands, but are less motivated by the faith itself – are often not raging fanatics, but combatants with goals and interests. And where these people are to be found, a window opens: to seek dialogue, to negotiate where possible.

The Afghan government recently made the Taliban an offer of far-reaching talks: recognition as a political party, prisoner release. After 17 years of war, a third of Afghans are again living under Taliban rule today. Keeping them at arms' length from the 2001/02 Petersburg talks on the future of the country is now seen as a momentous error.

In the Sahel states, Brussels, Paris and Washington continue to invest in the military option alone. When France intervened in Mali in 2013, the comparison with Afghanistan ("Sahelistan") still appeared absurd, but after five years of international intervention, Mali is marked by a complex grid of violence. Barely a day goes by without attacks, most of them aimed at foreign troops (12,000 UN soldiers, including 1,000 German and 1,000 French special forces).

Cautiously open to dialogue

The Malian peace process only includes non-Islamist militias, in particular the Tuareg rebels who initially triggered the crisis. The approach to their intermittent jihadist allies is: don't talk to them, just liquidate them. For Mali, this distinction between partner and enemy has always been imposed from outside. Many regard the Tuareg separatists as the greater evil: after all, they caused so much mayhem in northern Mali that successive religious occupiers were initially welcomed as a force for peace and order.

From 2014, a number of key figures in Mali began lobbying for a dialogue with the jihadists. The calls gained more traction as attempts to militarily vanquish jihadism failed. Furthermore, this attitude is today more evidently domestic than in previous years; the Malian people took less umbrage at the Western liquidation strategy, as long as those killed were foreigners.

Now two well-known actors are putting their heads above the parapet: in central Mali the preacher Amadou Koufa and in the north the Tuareg leader Iyad Ag Ghali – the latter the personification of the fluid dividing line between rebellion, terror, the drugs trade and al-Qaida in the Maghreb. Both leaders have indicated a cautious willingness to enter into dialogue. And despite all the crimes that have been committed, many Malians still feel a certain sense of respect. "We can't throw these people in the river. We need a political solution," says the politician Tiebile Drame.When last year the 900 participants of a "Conference of National Understanding" also called for an attempt at dialogue, President Ibrahim Boubacar Keïta had his reconciliation minister announce: "Mali is ready to negotiate with all its sons." Just a few days later, he withdrew his offer under pressure from France. On a visit to Mali, the foreign minister at the time Jean-Marc Ayrault said categorically that in the fight against terrorism, there was "only one way, not two" and the Malian President promised obedience.

"It was shocking to see how limited our room for manoeuver is," says opposition member and ex-foreign minister Sy Kadiatou Sow. "Mali is de facto under guardianship. But we must have the courage to debate what's good for us, for our nation," she says. The politician is known as a champion of women's rights; no one is suggesting she has any sympathy for a radicalised Islam.

Both the northern Irish IRA and Palestine’s PLO were previously regarded as ultra-terrorists with whom talks would never be possible. The extent of the crimes committed should not be a barrier to engagement, writes Jonathan Powell in his book "Terrorists at the Table". Tony Blair's former chief of staff, an expert in international conflict mediation, proposed talks with al-Qaida 10 years ago.

Nevertheless, the idea still persists that no rational dialogue can take place with jihadists because these are religious fanatics with crazy Caliphate fantasies, without regard for current local social circumstances. Yet this hardly applies to Africa.

Jihadism in reaction to state despotism and social injustice

Leonhard Harding, emeritus professor of African history at the University of Hamburg, writes on the Sahel jihadists: "A joint concept for the creation of an Islamic state or the declaration of a new Caliphate is nowhere in sight." The fighters are primarily interested in local reform and wanted to win the support of the people, he continues. On the subject of Boko Haram, the French political scientist Jean-François Bayart says this is "the religious expression of a social phenomenon."

Even in 18th and 19th century West Africa, so-called jihadists battled against unjust rulers using religious slogans. In a similar way, today's jihadism in central Mali presents itself as a response to state despotism and social injustice. The region is wracked by a movement that identifies terrorism as social rebellion.

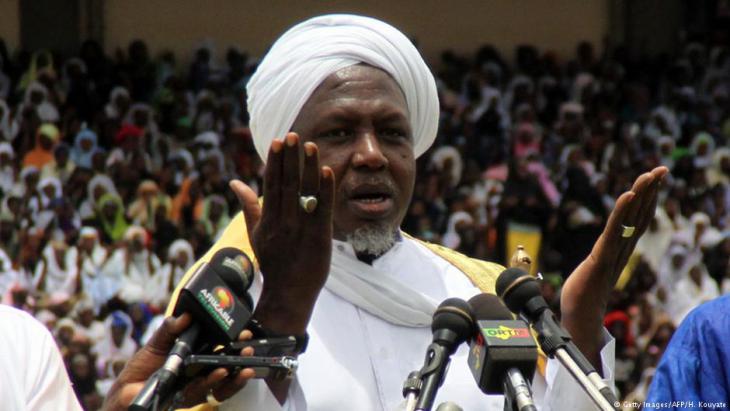

Recruits are often found among young Fulba shepherds; they expel representatives of a state that they only know as the repressor, execute tax collectors and mayors. When a judge was abducted in broad daylight, the local population reacted with "satisfaction", reports a film director from the region. "When things like this happen, I hear the same thing each time: 'the civil servants had it coming to them!"In a prevailing mood such as this, the head of Mali's High Islamic Council is now seeking ways to instigate dialogue. Mahmoud Dicko, a politically agile and religiously moderate Wahhabist Muslim, initially invited the heads of Koran schools and traditional authorities in the region to several large-scale gatherings; 800 responded to his call. They exert their greatest influence in the places where the state is no longer present and they can therefore establish contact with key figures in the jihadist movement for Dicko.

"I aim to open paths to dialogue by asking what we can do for the region." Where possible, he continues, beyond the parameters of the official justice system which is so corrupt it affects the poorest members of society in particular, the appointment of traditional Islamic judges (Kadis) could have a positive effect.

Others send killer drones

"We must encourage the population to exit the vortex of violence," says Dicko. "But where is the red line that a republic cannot cross? That's something that the nation, the people must decide." He has no official mandate for his efforts.

A retired Malian general well-disposed to the West, with good memories of his training at the Military Academy of the German Armed Forces in Hamburg, describes a possible scenario following the withdrawal of foreign troops thus: "Then we would negotiate with the jihadists and if they want to introduce Islamic law, then we will see exactly what this might look like. Maybe it's not that bad. The jihadists want a clean jurisdiction and on some questions they are right."

Whether and how negotiations can take place must be determined separately according to the specific location. And no one wants to predict the chances of success. But many experts say it is at least worth a try.

"You can't kill all the jihadists. In Mali too, there is no alternative but to negotiate," says the head of the Berlin Centre for International Peace Operations, Almut Wieland-Karimi. Even the German Foreign Ministry is now saying that this is first and foremost a decision made by Malians.

The choice is dialogue or war

Twelve researchers from Mali, Senegal, the US and France recently warned the French government that by blocking attempts to initiate dialogue, it was running the risk of standing "on the wrong side of history". The military approach should be subordinate to a political goal that must be determined by the societies of the Sahel, they said.

To regain national sovereignty in the fight against terror is something intellectuals in the region are also calling for, individuals such as Moussa Tchangari, who heads the "Alternative Espaces Citoyens" in the capital of Niger, Niamey. In Mali, Niger and Nigeria negotiations with jihadists were always permitted whenever they served to secure the release of western hostages, he says.

This shows, he continues, to what extent "the decision on whether to enter dialogue or war is dominated by the interests of the major powers of the West." Indeed: in a situation of this sort, the French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian once issued a delicate reply to the question of whether the notorious Iyad Ag Ghali was a terrorist, saying: "It's up to him to say what he perceives himself to be."

Citizens' calls for greater national autonomy in Mali and Niger have so far gone unheeded by governments there: because foreign military presence bolsters their power and bloated defence budgets secure income from corruption.

Poverty-stricken Niger devotes 15 percent of its budget to its military – and is now, for the first time, allowing the U.S. to send killer drones to the Sahara from a new base.

Charlotte Wiedemann

© Qantara.de 2018

Translated from the German by Nina Coon