Transcending the secular-sacred divide

On the face of it, 'Islamic secular' sounds like an oxymoron. Although the adjective 'secular' is a loaded term, in modern academic parlance, it's commonly used as antithetical to 'religious' or 'sacred'. The secular-sacred dichotomy is so entrenched in Western/Euro-centric discourse that an act, idea, or institution can be described either as religious or secular, but never both.

While 'secular' is associated with development and modernity, 'religious' is often used to refer to backward and pre-modern. While the indignant 'sacred' blames 'secular' for unleashing profanities and debaucheries on the world, the self-righteous 'secular' takes upon itself the mantle of liberating the state, economy and science from the clutches of outdated religion.

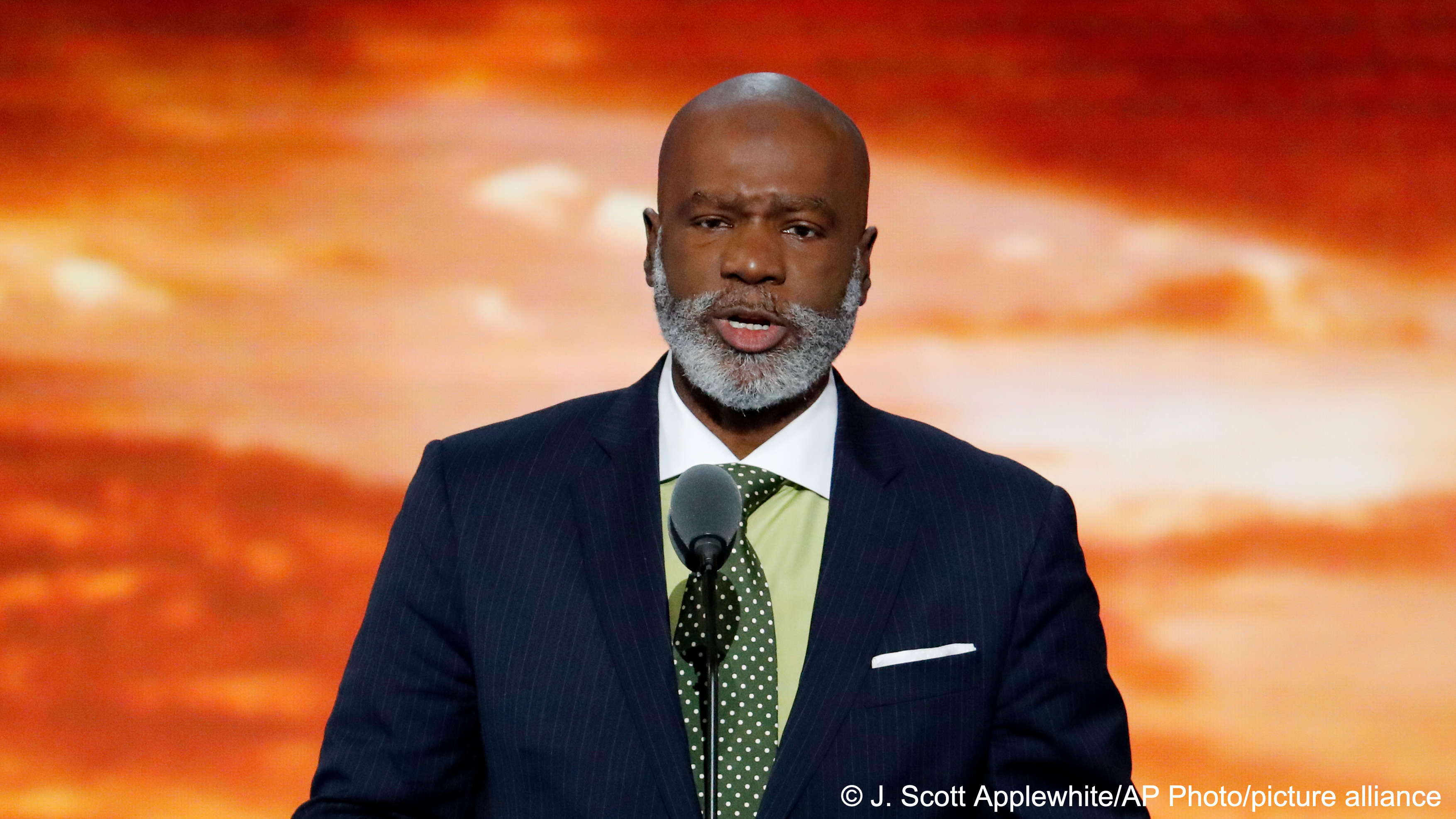

In his latest book "The Islamic Secular", Sherman Jackson, professor of Religion and American Studies and Ethnicity at the University of Southern California, contends that the Islamic legal tradition, particularly usul al-fiqh, points to an alternative understanding of the secular, which is neither outside religion nor a rival to it. He argues that the wholesale grafting of the Western perspective of the secular onto Islam has generated significant inaccuracies and blind spots in understanding the 'Islamic secular'.

Non-Sharia as Islamic Secular

Jackson postulates that the 'religious' in Islam cannot be confined to the sacred law commonly known as 'Sharia'. Islam has a broader jurisdiction encompassing all aspects of human life, cutting across its secular and sacred dimensions, while 'Sharia' – representing God's concrete communique – remains a bounded entity. Even classical Muslim jurists did not consider Sharia as an all-encompassing exclusive means of determining what is Islamic.

Jackson defines this non-Sharia realm as Islamic Secular because it is still within the broader parameters of Islam as religion. Islamic secular encompasses everything that falls outside the dictates of Sharia, yet is potentially Islamic, because it falls within the wider framework of Islam as a religion.

"Between the circumference of Sharia and that of Islam as a whole, there exists a space within which Muslims do not and cannot rely solely on concrete divine dictates. Yet while operating within this space, Muslims are neither removed from nor necessarily seek to remove themselves from a conscious awareness of the presence and adjudicative gaze of the God of Islam."

For example, the marvellous buildings designed by the great Ottoman architect Sinan or the observatory in Samarqand founded by Ulugh Beg in the 15th century became signatures of Islamic architecture or science, not because they were built based on the concrete instruction of God, but because they were carried out with a "sustained devotional intent".

What is the essence of Islam, and does it need reforming?

Renowned Jordanian Islamic scholar Fehmi Jadaane vehemently objects to the transformation of Islam into an ideology. The religion ends up mired in a political swamp, he says, its message nothing more than an instrument of governance. Interview by Alia Al-Rabeo

Non-Sharia as Islamic Secular

According to Jackson, both these projects fall within the province of Islamic Secular. They are all secular because God's revelation contributed almost nothing to their concrete substance. Yet they remain religious/Islamic because their efforts were informed by "a conscious awareness of the divine gaze", making them not different from any religious act of worship (ibadah).

Unlike the God of Sharia who simply commands, the God of Islamic Secular generates in humans "a heightened consciousness, an elevated sense of expectation, and a desire to appease beyond the fulfilment of God's concrete commands".

Jackson warns that given the centrality of non-Sharia/secular activities to our everyday existence, any attempt to exclude them from the designation of Islamic, thereby stigmatising them as non-religious, will "affect Muslims' perception of the quotidian efficacy of Islam and of themselves whenever they engage in activities commonly deemed to be secular".

He says the tension between the religious ideal and the human real will either trigger civilizational failure, as it will drive Muslims to embrace secularisation in the modern Western sense, or civilizational schizophrenia, pushing them further towards a totalising and absolutist vision of Sharia promoted by Islamist movements.

Islamic Secular also addresses the problems posed by the conflation of culture with religion. According to Jackson, "the tendency to universalise the achievements of the traditional Muslim world as the sole possible plausibility structure for Islam stifles what might prove to be a more effective alternative". The "composite Islam" he calls for is inclusive of much more than is derived concretely from the sources of religion, including people's rich and vibrant lived reality in any given time and place.

Broadening the circle of 'Islamic'

Jackson lays the theoretical foundations of the Islamic Secular by critically engaging with a plethora of luminaries in the field of Islam and secularism such as Talal Asad, Wael Hallaq, Abdullahi An-Naim, Andrew March, Toshihiko Izutsu, Marshall Hodgson and Shahab Ahmed. His theory of Islamic secular has much in common with Shahab Ahmed's broader definition of Islam in his posthumously published tome "What is Islam".

Ahmed sought to expand the possibilities of 'Islamic' beyond the limited realm of 'Fuqaha-Jurisprudents' and the scope of the revelation beyond God's Text to include all sorts of hermeneutical engagements with it, which he described as Revelation's Pre-Text and Con-Text. Ahmed even went to the extent of imputing to such engagements an authority that is equal to that of the Text.

Jackson disagrees, however, with Ahmed's suggestion that Text could be dependent on anything behind and beyond Revelation. He says the authority of Con-Text would be "provisional, secondary, and subject to expiration", whereas that of the Text is "original, primary, and enduring".

In his discussion of the philosophical legacy of Greek antiquity, for example, Jackson advocates a concept of the dynamic and accumulative tradition, stating provocatively that the fact that "Aristotle and Plato were not Muslims is simply irrelevant to their meaningful designation as Islamic". But Jackson excludes the contributions of non-Muslim from Islamic secular if they were not "mediated through a process of validation over which Muslims preside".

He fails to portray a convincing picture of this validation process, but cites rather a frail example: a hijab-wearing Barbie will only become an Islamic doll through validation brought about by acceptance and popularity among Muslims.

In short, Islamic Secular seeks to broaden the circle of 'Islamic' by bringing in acts that are cordoned off as secular or non-religious to the fold of Islam, but, unlike Ahmed's "What is Islam", cautiously stops short of casting a blanket Islamic net.

The book also casts aspersions on the ability of 'the present deployment of western languages', especially English, to accurately depict the Islamic faith.

© Qantara.de 2024

Muhammed Nafih Wafy is a writer currently based in Abu Dhabi.