Conformist Provocations

Egyptian mega-star Adel Imam is the Arab world's most famous and best-loved comedian. And its biggest box-office magnet. In Terrorism and Kebab he plays a minor civil servant, the "everyman" Ahmed, who undertakes, in vain, to transfer his children to another school in repeated visits to the Mugamma, the central public and police office for the mega-city Cairo, with some departments in charge of the entire country.

He surfs his way through the sea of bodies crowding the corridors of the government building. Only after several rounds is he able to turn off into the right office. Having arrived at his destination, he finds a woman sitting at her desk hysterically chattering to a girlfriend on the phone. She offhandedly passes Ahmed on to her colleague, a member of the Muslim Brotherhood engrossed in ceaseless prayer.

Between words of praise, he refers Ahmed further, to his brother department head, who is either away at a training course or has left the building to use the toilets elsewhere – he is after all a fine gentleman and does not deem the facilities at his own office good enough for him, says the chatterbox.

A government office as mirror of society

Screenwriter Wahid Hamed uses the scene at the Mugamma to address a whole host of injustices in the Egyptian system. The humour here comes from the grotesque exaggeration of what are already stereotypical characters:

A soldier who, like the village idiot, lets himself be bossed around by a higher civil servant, not only dusting his desk but also babysitting for his children; a shoeshine man on the stair landing who tells Ahmed how he was cheated out of his plot of farmland at the agency; a woman mistakenly arrested for prostitution who refuses to sign a false confession and proceeds to retrieve a whole arsenal of make-up out of her décolleté; and a Nubian who, contrary to the cliché of his underdeveloped race, begins every sentence with "In Europe and the advanced nations".

Ahmed is unable to turn up the department head in any of the fancier toilets in the area. On his way back to the Mugamma he spies an older gentleman on the street whom he earlier heard railing on the bus about the decline of morals and the increasing religiosity and stultification of society. Hoping he might be Brother Department Head, Ahmed sprints back to the government building and announces that he will wait there as long as it takes for his case to be processed.

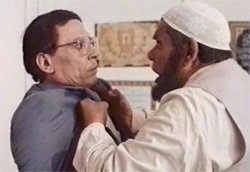

This gets him into a fight with the Muslim Brother, who just wants Ahmed to let him be. Ahmed says that the office is no place for religion. The two come to blows, the female office worker calls the security guards and, as Ahmed is being arrested, a shot rings out. It has been fired by Ahmed, who keeps hold of the rifle and, slightly confused, declares those still present to be his hostages.

With Ahmed's resolve to take action, the film departs from the genre of comedy. All of the hurdles set up thus far in the story now seem to have been swept away. As Ahmed sprints back up the stairs to the office (the fine gentleman has already been forgotten), the corridors are almost empty, the chatterbox is not talking on the phone for a change, and she is suddenly automatically able to call in the security guards. Only the Muslim Brother continues to pray, thus catalysing the problem.

Provocations without discussion

Wahid Hamed is a successful and well-known screenwriter; stories about him fill whole pages of the newspaper and in the early 1990s his was already a household name. The derogatory depiction of piousness is one of his trademarks, along with provocation and the breaching of taboos. He does not however really delve into the latter, but rather only touches on them in passing without any further discussion.

Only the odd characters described above show solidarity with Ahmed, with the exception of the well-educated Nubian. All the others are hostages. The antagonism between government and populace is transformed into one between terrorists and upstanding citizens, between good and evil. Once again in this film, the author does not take a closer look at the situation. He does not linger on the irony that Ahmed is himself a civil servant and that his desperate act has resulted from the indifference he has encountered at the government agency. Ahmed would have had to formulate an agenda to deal with this, but he doesn't have one.

Twice the Minister of the Interior, who has stationed himself before the Mugamma with a whole battalion of policemen who are armed to their teeth, gives him a chance to state his demands. But the hostage-taker Ahmed merely stammers incoherently and then abruptly asks his hostages if they're hungry. He conveys their request for kebabs to the minister, who in return offers Kentucky menus. The people are not about to stand for this and start chanting loudly through the open windows "Kebab! Kebab! Or we'll make your lives hell!"

When the minister later tries once again to get Ahmed to state his demands, the latter merely laughs and says he doesn't have any. He came to the agency to transfer his children to another school. He is no different from all the others, he says, who then one by one reveal their worries and express their indignity over the political situation, but in a silly and uninformed way. This is not the stuff of which true demands are made. When the Mugamma is peacefully evacuated, Ahmed is able to leave the building incognito under the cover of the mass of hostages. The next day is dawning and everyone exits the cinematic stage.

A comedian who can't take a joke

Even though the film exceeds the bounds of comedy in formal terms, the way it simply sweeps under the rug any inconsistencies instead of using this central element of the genre to playfully open a discussion means that most of the audience find it merely amusing. The laughs are prompted by Ahmed's presumption in thinking he might start an uprising. The audience laughs at these rebel wannabes.

The joke at the beginning of the film, a plaque on which the film crew thanks the Minister of the Interior and the security forces for their understanding and support with the making of the film, is dead serious. The film was shot on location – a rarity for Egyptian mainstream movies – calling for the Mugamma to be evacuated and a genuine police battalion called in. This is of course only possible with the active assistance of the government.

Director Sherif Arafa later became a member of the media team for Mubarak's 2005 election campaign, and in February 2011 he was responsible, together with filmmaker Marwan Hamed, a colleague from the campaign team, for coordinating the compilation film 18 Days, the "film of the revolution". Adel Imam has publicly endorsed Mubarak, even after he stepped down. The honour of his president is after all no laughing matter.

Irit Neidhardt

© Qantara.de 2011

Translated from the German by Jennifer Taylor

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de