Self-criticism and genuine dialogue required

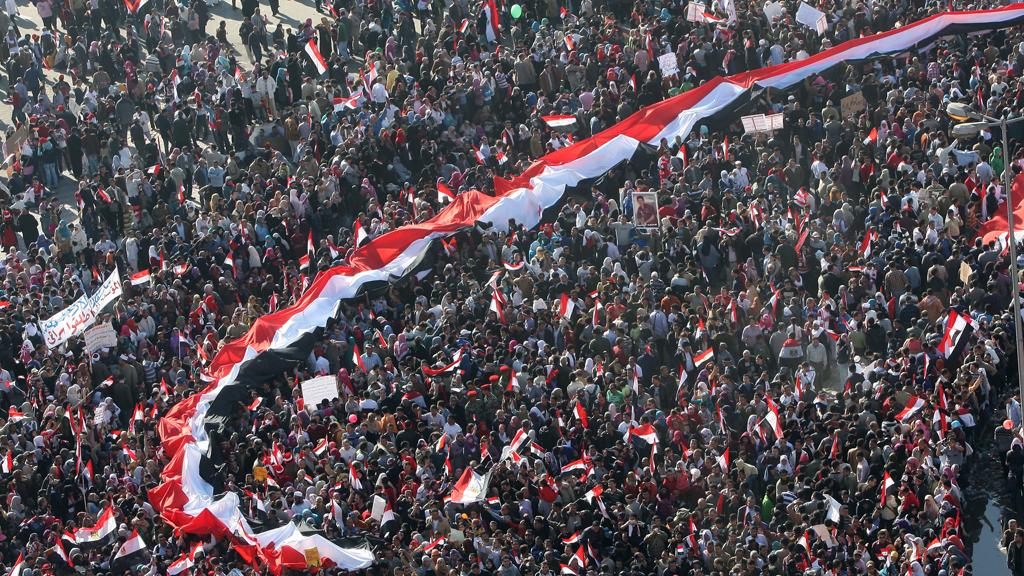

Experiences in Egypt and Tunisia, which served as an experimental laboratory for the rapprochement of various political movements in the first three years of the Arab Spring, show that much more divides Islamists and secularists than unites them.

Much more important than this, however, is the fact that their true weakness is now coming to light, namely their inability to realise the democratic intentions they so vociferously and rhetorically expounded. All players declared themselves clearly on the side of democracy, but without exception, they failed miserably in their first attempt to achieve these intentions.

And so it was in Egypt, where the Muslim Brotherhood, which came to power with the help of the left and the liberals, made fools of its allies by exercising its authoritarianism under the pretext of a "dictatorship at the ballot boxes". In response to this, their opponents among the liberals and on the left took the first opportunity that presented itself and did not hesitate to make common cause with the counter-revolutionary forces of the old regime in order to topple their political opponents.

The exact same thing is happening in Tunisia, even though the power struggle there was not as violent as it was in Egypt. When Tunisia's Islamist "Ennahda" party tried to impose the main features of its social model on the new Tunisian constitution, left wingers and secularists felt it necessary to join forces with the remnants of the ousted regime to block these efforts.

Three years of diverse political alliances of convenience, moments of crisis and outright confrontations between key political forces have made one thing clear, namely just how deep the chasm is between them and how high levels of mistrust continue to be.

Ideological trench warfare

But have steps been taken to reflect upon the setbacks experienced by these states in transition and the underlying causes of the apparently insurmountable differences between the competing groupings? There have already been some positive developments. For example, all sides appear to have understood that an exclusively rhetorical discourse is not appropriate for the prevailing political reality.

The greatest loss is the loss of trust between political forces, a trust that was too brittle to withstand reality and that can only be re-established through hard work built on transparency and genuine dialogue.

The greatest loss of trust was caused by the fact that the various groupings preferred to enter into alliances driven by one common goal, namely opposition to the despotic regimes in their nations, instead of establishing clear competitive connections on the basis of political programmes.

Reaching an understanding is also being hampered by the fact that despite their fundamentally different socio-political concepts, the different movements are essentially arguing over the same terminology, the same clientele and the same major issues.

And then there is the clear lack of democratic tradition in Arab societies, which was reflected in the predominance of the "majority dictatorships" that followed the toppling of the old regimes. Once these dictatorships were overthrown, however, too little attention was paid to building up a culture of consensus. The experiences of these Arab states in transition show how urgently democratically-aligned figures of integration are needed to serve as "bridge builders" between the opposing sides.

Even before the outbreak of the revolutions, there were occasional moments of co-operation between the various political players, in particular when the repression exerted by oppressive regimes got out of hand.

This dialogue, which took place under the "enemy fire" of a "deep state" that tried to prevent alliances of this nature, did produce some positive results, which consequently impacted on the development of relations between the various parties.

Modesty as a virtue

It would certainly have been beneficial for the "democratic experiment" in the nations affected by the Arab Spring if all sides had remembered that modesty, as expressed in the "realism" of "Ennahda" in Tunisia, is a virtue.

The fair democratic elections, which took place in Tunisia and Egypt before the Egyptian military coup of 3 July 2013, showed that no political force was able to capture enough of the vote to assert its particular social model.

Although the Islamists nominally won the poll, they did not gain an absolute majority from Egyptian voters. For their part, the performance of left-wing, secular and liberal forces revealed a weakness that bore no relation to their strong media presence. What's more, the rapid fluctuations in the balance of power revealed how weak and fragile the left-wing, secular and liberal camps' belief in fundamental values such as democracy, freedom and the rule of law was.

In other words, until such time as the real change heralded by the winds of the "Arab Spring" comes about, everyone will remain a loser: left wingers, Islamists, secularists and liberals alike. Genuine change can only come to pass if all forces undergo a process of serious self-criticism and political reflection.

Moreover, a political and intellectual dialogue between the opposing groups is urgently advisable – all the more so because they must now have realised that true democratic change requires the efforts of all forces.

For years, however, the only rhetoric that characterised the political dialogue was that of the exclusion of the opponent: over the course of a bitter battle lasting many long years, the only thing each side sought to do was to distance itself from the other.

The need to work together

After the coup in Egypt – and also in view of Tunisia's uncertain path – activists representing precisely these politically influential forces in Tunisia, Morocco and other Arab nations as well as Egyptians living abroad, have begun to seriously reflect on how they can work together to set the ground rules for a more transparent and serious dialogue. However, genuine dialogue will depend on all participating parties being in a position to further develop their ethos and their political programmes and to organise these in a way that is more in keeping with the times.

In Morocco too, where the first steps towards such a dialogue have already been taken, the path is still long and stony because any serious dialogue must begin with agreement over fundamental democratic principles as the common political denominator. These rules must be accepted as the tools of conflict resolution in order to create basic conditions for the safeguarding of societal peace.

In order to keep conflict to a minimum, civil society must also be integrated into the dialogue, as is the case in Tunisia, where trade unionist and civil organisations served as arbitrators, negotiators and "saviours in the hour of need" when huge political confrontations arose during the attempt to hammer out the new constitution.

The establishment of these basic conditions appears to be acutely necessary. After all, who would benefit from the trench warfare being waged between the various opponents? None other than the same old forces who are intent on sweeping everyone else aside so that they can once again impose totalitarian rule on Arab populations and control their destinies.

Ali Anouzla

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Nina Coon

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de