A renewed partnership?

Syria and Turkey have been engaged in military conflict for over a decade. Ankara and Damascus are now working to resolve their differences. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has expressed interest in renewed cooperation with his Syrian counterpart Bashar al-Assad. Assad has conveyed a similar desire to improve relations. The current geopolitical situation also offers incentives for settling the conflict, and many of the initial causes of tension have been diffused.

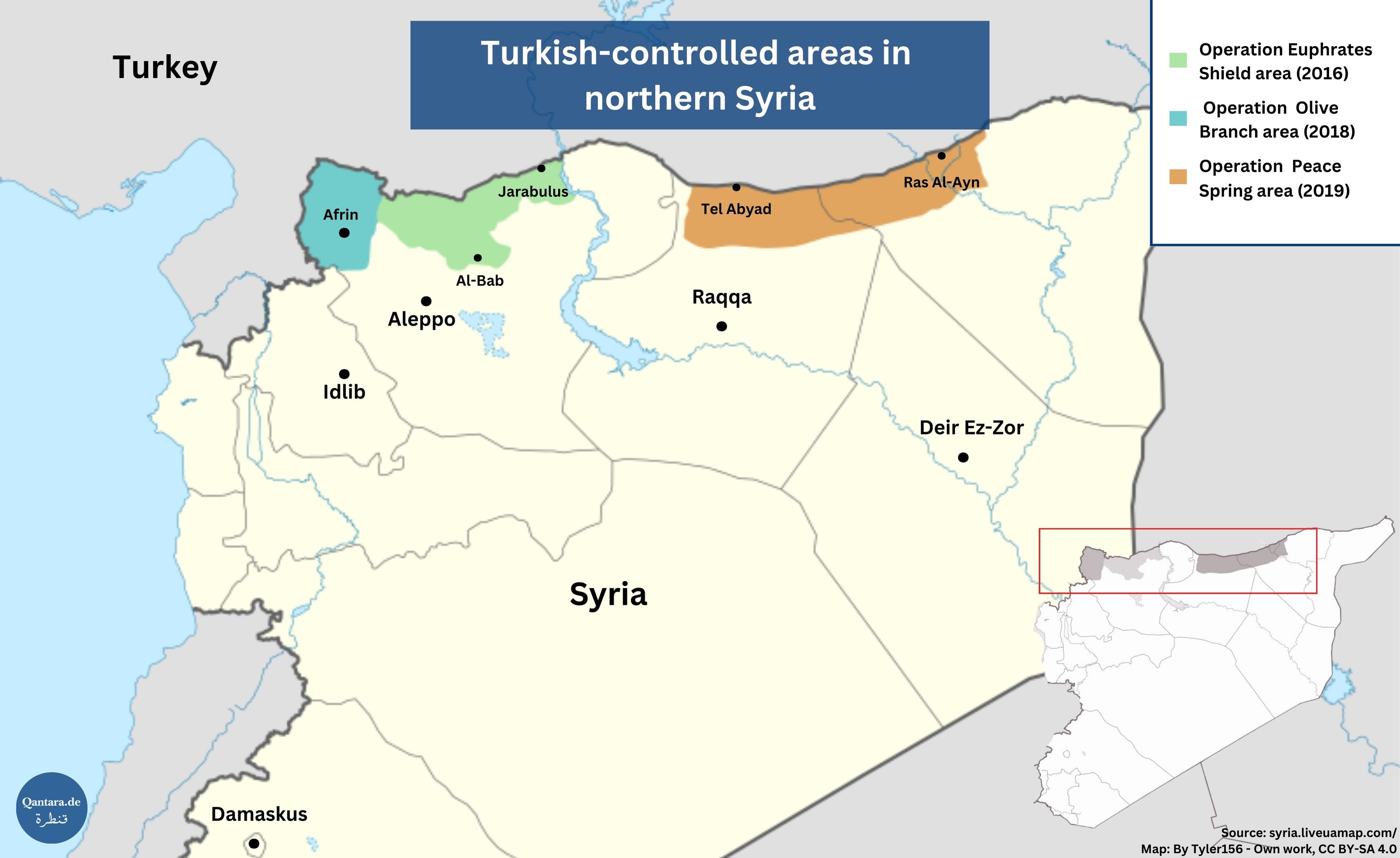

Turkish armed forces control three separate areas in northern Syria, including cities such as Afrin, al-Bab, Jarablus, Tel Abyad and Ras al-Ayn. Turkey's military operations (in 2016/17, 2018 and 2019) and the occupation of northern Syria are largely regarded by the international community as illegal under international law. At the same time, however, there has been no condemnation from the United Nations.(1) Ankara wants to settle Syrian refugees, whose number in Turkey has risen to over three million, in the Turkish-controlled area. The Syrian government seeks to restore the country's territorial integrity and is demanding the withdrawal of Turkish troops.

In the years before the civil war, there was little conflict between the two nations. Between 2001 and 2011, bilateral relations grew stronger in almost all areas. Trade increased from $744 million to $2.1 billion, with Turkey enjoying a surplus of $1.1 billion. In December 2010, representatives of Syria, Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey met to negotiate a free trade agreement in Istanbul. In January 2011, Turkish newspaper Hürriyet described the relationship between Syria and Turkey as a “model partnership”. The value of property owned by Turkish citizens in Syria rose from $40 million to $10 billion over the period. In 2011, 974,000 Syrians visited Turkey, and 1.35 million Turks visited Syria.

Dreams of a Kurdish corridor

The civil war in Syria put an end to Turkish-Syrian cooperation. The Turkish government initially sought to convince Assad to agree to democratic reforms and economic liberalisation. When the diplomatic approach failed and the situation came to a head, Turkey—in line with US strategy—promoted regime change. It allowed the Syrian opposition to establish the Syrian National Council on Turkish soil and supported the Free Syrian Army in its mobilisation against the Assad regime.

As time went on, diverging positions and conflicts of interest between Turkey and the US emerged. Ankara complained to Washington that the US was not vigorous enough in its efforts to topple the Assad regime. The US administration under Barack Obama, in turn, believed that Turkey was not contributing enough to the fight against the Islamic State (IS).

The assassination of the US ambassador in Benghazi, Libya, on 11 September 2012 marked a turning point in Turkish-US cooperation in Syria. The attack, which was initially attributed to al-Qaeda, exacerbated differences of opinion between Ankara and Washington about which groups should be supported in Syria.

In 2014, the Obama administration decided to support the Kurdish People’s Defence Units (YPG), the military arm of the Democratic Union Party (PYD), and to airdrop weapons to Kurdish ground troops to support their fight against IS. The decision proved to be explosive for Turkish-American relations. Ankara saw the move to arm the YPG as a slap in the face.

After the YPG defeated IS in the siege of Kobani, Kurdish troops began to advance westwards across northern Syria. Only a few kilometres separated Kurdish troops from the Mediterranean and the establishment of a Kurdish corridor across northern Syria. In Turkey’s rhetoric, this would have been a “corridor of terror”, almost completely separating Turkey from the Arab world by land, as Kurdish forces also control the autonomous Kurdistan Region in northern Iraq.

Turkey aimed to prevent what it saw as a geopolitical disaster. It launched its first ground offensive into northern Syria in the late summer of 2016. Ankara feared that a Kurdish autonomous region in northern Syria would represent an attractive alternative political model for Kurds in Turkey and become a military refuge for the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK).

The Turkish offensives in northern Syria, which established direct military control over the three zones in northern Syria plus large parts of the Idlib province, put an end to Kurdish ambitions for autonomy.(2) The dream of a Kurdish corridor from northern Iraq to the Mediterranean was over.

United by a common threat

Today, the common interest of Turkey and Syria is to prevent the establishment of a PYD-administered autonomous region. Ankara and Damascus are both concerned that the PYD is just waiting for the opportunity to arise. This shared threat forms a solid basis for a bilateral compromise but is incompatible with the stance of the German government, which disapproves of Turkey's actions against Kurds in Syria and sees no justification for the normalisation of diplomatic relations with Syria.

An additional priority for the Turkish government is to defuse the refugee crisis. Turkey is home to over three million refugees from Syria alone and around two million from other countries. It lacks the economic capacity to integrate five million refugees. Against this backdrop and given the growing anti-immigrant sentiment throughout the country, the resettlement of Syrian refugees in northern Syria is becoming an increasingly urgent objective. Resettlement would require cooperation between Ankara and Damascus. Assad's recent general amnesty is seen as a step in this direction. According to experts, it could encourage the voluntary return of refugees from Turkey to Syria.

Regional conflict has also created new incentives for bilateral rapprochement. For the West, the war in Gaza since October 2023 has upgraded the Middle East’s status as a geopolitical priority, making a “return” of the USA to the region more likely. Current tensions between the US and Iran as well as Iran's military confrontation with Israel—both directly and via Iranian proxies in the region—suggest that Tehran will not be able or willing to provide decisive support to the Syrian government. This would be another incentive for Damascus to smooth relations with Turkey, as rapprochement would strengthen Syria's position vis-à-vis Israel, which would in turn also benefit Turkey.

Ankara wants a say in Syria's future

However, there is a strategic ambiguity in Ankara’s attitude towards Damascus. Though Ankara has repeatedly spoken out in favour of Syria’s territorial integrity, Turkish administrative structures in northern Syria, and the development of infrastructure (road construction, water and power supply, telecommunications, etc.) are fuelling fears that Turkey may envisage a long-term occupation or even an annexation of the territories it occupies, when the moment arises.

Ankara will likely insist on having a role in shaping Syria. It is likely to demand that Syria works to improve the status of Turks in Syria and recognise the province of Hatay as part of Turkey—in 1938, a referendum in Hatay led to its annexation by Turkey, which has never been recognised by Syria. Finally, Ankara is likely to push for the reactivation of the 1998 Adana Agreement. This agreement obliges Turkey and Syria to cooperate closely in the fight against terrorism. It includes assurances that PKK activities will not be tolerated on Syrian territory.

A decisive factor in any rapprochement between Turkey and Syria will also be whether the future US administration favours cooperation with the PYD or approaches Turkey to secure its support in a potential confrontation with Iran.

Overlapping perceived security threats are bringing Turkey and Syria closer together. A settlement of the bilateral conflict could help to promote stability in the region, alleviate the pressure of migration and facilitate its management. This would also be in the interests of the German government, as it could strengthen German security. But it could also lead to a change in the regional balance of power, posing new challenges for German foreign policy.

Notes:

-

To justify the military operations, Turkey invoked the right of self-defence under Article 51 of the UN Charter and referred in a letter to the UN Security Council (20 January 2018) to a terrorist threat as a result of the Syrian Civil War. According to the judgement of the Research Service of the German Bundestag, the Turkish offensive constitutes a clear violation of the prohibition of the use of force under Article 2(4) of the UN Charter.

-

The Turkish occupation has been criticised and accused of serious human rights violations, war crimes and expulsions of Kurds, Yazidis, Assyrian and Armenian Christians living in northern Syria. Turkey is also accused of deliberately changing the demographic composition of northern Syria “to the detriment of the Kurdish population as well as the ethnic and religious minorities, the Armenian and Assyrian Christians.”

© Qantara.de