Beards and hijabs behind bars

It was easy to overlook the narrow, nondescript staircase leading to a brightly-lit basement mosque in Istanbul's busy Sultan Murat neighbourhood. Below, a small girl ran around among the white and gold columns, while a dozen men, most of them still wearing winter coats, prayed on the pale blue carpet. The men are all Uighurs, a Muslim community based in the Xinjiang Uighur Autonomous Region of north-western China.

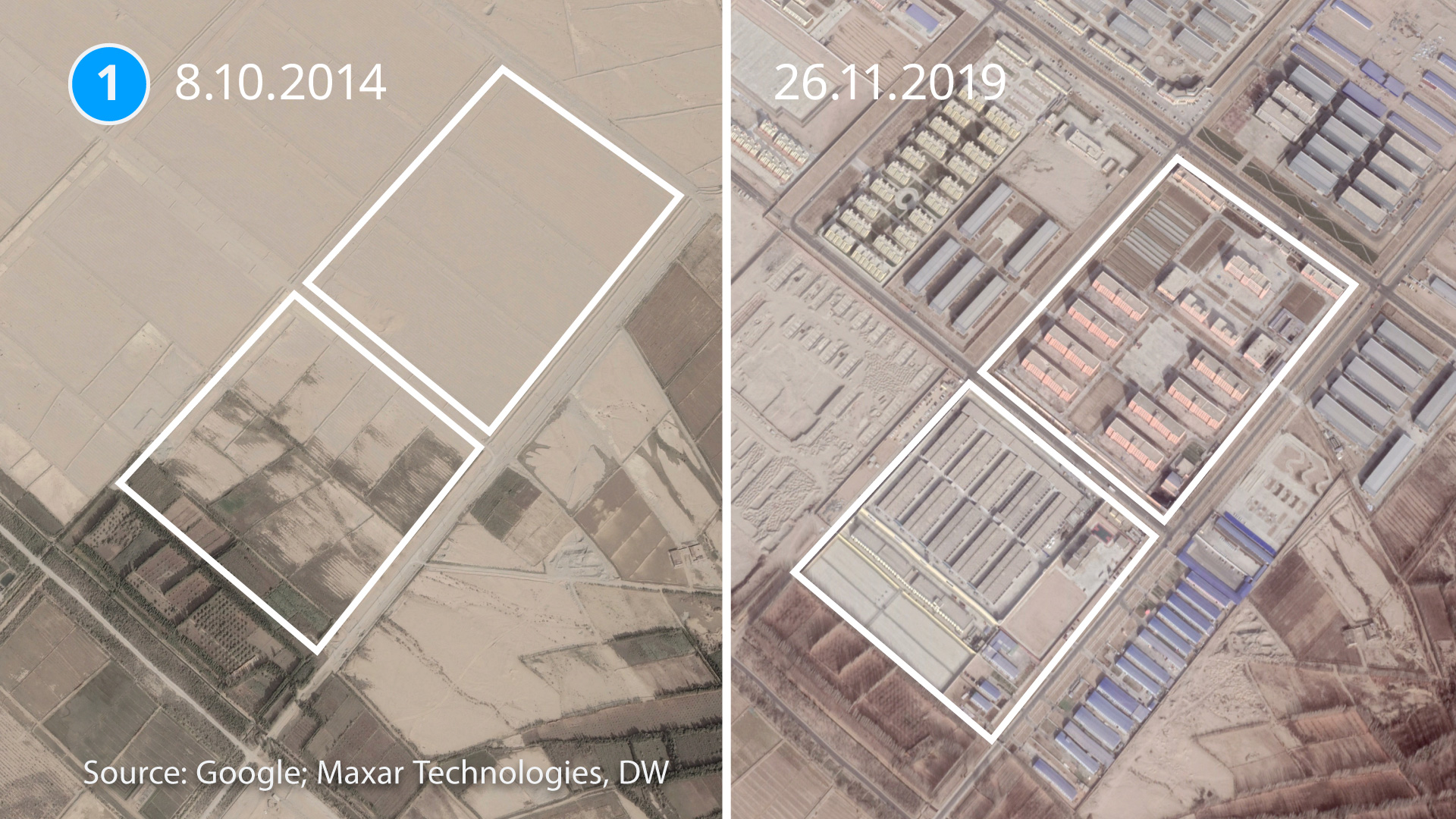

Back in Xinjiang, these afternoon prayers would have been a dangerous act. Since 2016, the Chinese government has been arresting Uighurs and imprisoning them in what are officially called "Vocational Education Training Centres", but have been referred to in the West as "re-education" camps.

The men all raised their hands when asked how many of them have relatives in Xinjiang who disappeared into China's network of prisons and camps. They then pulled out their smartphones and showed photos of their relatives' identification cards; pictures of wives, children and parents who have disappeared without a trace.

"I don't know if my daughter is even alive or not," said one man looking at a picture of a young, slim woman.

"The Chinese government wants to take full control and eliminate all people who live there," the mosque's imam exclaimed, gesticulating angrily. "They want to kill the Uighurs and our culture."

Imprisoned for their faith and culture

It is hard to say exactly how many have been imprisoned. According to estimates, at least 1 million of the roughly 10 million Uighurs living in Xinjiang have disappeared into the network of prisons and camps constructed by Chinese authorities.

Reports from the region show that some detainees are being held indefinitely, while others are moved to labour camps. Those who are allowed to return home are kept under the close supervision of local authorities, with their freedom of movement strictly limited.

Chinese authorities claim that the "vocational training centres" were built to fight "extremist ideas" and provide Uighurs with "valuable skills". At the camps, detainees are said to undergo a rigorous indoctrination process and take Mandarin language courses.

In a recent interview during a visit to Berlin, China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that several NGOs, journalists and diplomats had been granted access to Xinjiang and "they didn't see a single concentration camp or re-education camp". Wang added that "there is no persecution [of Uighurs] in Xinjiang."The prisoners of Karakax

While China maintains this official narrative, a new document obtained by the Deutsche Welle and German media partners NDR, WDR and the Suddeutsche Zeitung sheds a different light on the story. It shows that China is imprisoning Uighurs based on their religious practices and culture, rather than extremist behaviour.

The leaked document is 137 pages long, and meticulously lists the names and ID numbers of 311 Uighurs detained in 2017 and 2018. Their cases include unprecedented details of detainees' family members, neighbours and friends. The list of detainees mentions more than 1,800 people with full names, IDs and information on social behaviour — for example if someone prays at home or reads the Koran. Hundreds more are listed, however, without these details.

All of the cases listed are Uighurs from Karakax County, which belongs to Hotan Prefecture in south-western Xinjiang, near the borders of India and Tibet.

Although it represents only a small part of Xinjiang, the document reveals the staggering amount of data authorities have collected on Uighurs. Their every move in Xinjiang is monitored by security cameras with facial recognition software and mandatory smartphone apps.

Some people were targeted because they had more than the legally permitted number of children, others because they had applied for a passport. Some men were detained simply because they grew a beard. One was detained because he downloaded a religious video some six years ago.

Several experts agreed that the massive document, a single PDF file without any official stamp or seal, is likely authentic based on its content and language. Deutsche Welle also spoke to several Uighurs with relatives on the list who corroborated key facts.

"Arbitrary" arrests

Abduweli Ayup, an American-educated Uighur academic living in Norway, provided the document. Ayup spent 15 months in a Chinese prison after he tried to open Uighur language schools in Xinjiang.

Ayup decided to go public, despite the risk to his family back home. He revealed that he is already being monitored by the Chinese authorities. Several of his wife's family members in Xinjiang have been arrested in recent months. Shortly before being interviewed, he received a threatening phone call warning him to back off. "Yes, it's dangerous," he said with a shrug. "But someone should speak up and tell the world what is happening."

During a meeting at a hotel in Norway, Ayup explained his "shock" on first seeing the document. He quickly realised that China's system of internment had little to do with so-called extremism. "I thought: they are arresting people without any reason."

Ayup decided to do something and began looking for relatives of people listed in the document. He tracked down 29 of them, the majority living in Turkey, and started making phone calls. He said it was a harrowing task. Many people he called had not contacted their family back in Xinjiang for years, knowing full well that a phone call from abroad can solicit unwanted attention and lead to imprisonment.

Now it was up to Ayup, an earnest, soft-spoken man, to tell these Uighurs abroad that their relatives still in Xinjiang had disappeared into re-education camps. "I would tell them their family members had been arrested, and they would cry," he said.

"I am heartbroken"

One of the people Ayup reached out to was Rozinisa Memet Tohti, a housewife and mother of three in her mid-30s. Deutsche Welle caught up with her in a well-decorated apartment in Istanbul; the living room table was covered with sweets, fruits and nuts for the visitors. In an emotional interview, Tohti said she was heartbroken after she had been told that her youngest sister was on the list. "I couldn't eat and sleep for many days. I never thought my youngest sister would be in jail."

Tohti has many pictures of her relatives. One is of a young couple holding an infant, smiling shyly into a camera during a family outing in a park. Another is of an elderly man with a long beard and an earnest expression wearing a woolly hat.

Tohti held each picture with care, clutching them in her hands throughout the interview. These could well be the last mementos of her sisters and parents. She knew that her oldest sister and elderly parents were all imprisoned in 2016. A family friend who visited Turkey for business told Tohti about the arrests.

But she had yet to hear about the arrest of her youngest sister in March 2018. Her remaining relatives in Xinjiang have broken off contact, and Tohti was afraid that she would put them at risk by contacting them. Tohti's sister ran a cake shop with her husband, and she didn't seem like someone who was in danger of being arrested. "I was really shocked," Tohti said, as she struggled to hold back tears.

One child too many

In Xinjiang, people in rural areas are allowed to have three children, and people in cities can have two children. However, many Uighurs do not adhere to the policy, and have mistakenly assumed that the penalty will be a fine.

Tohti's youngest sister was arrested because she had too many children. The document describes her case in detail. According to a translation, the youngest sister "currently doesn't pose harm" and she is set to "graduate" from the "vocational centre" and be "monitored by the community." She had also heard rumours that prisoners' organs were removed and sold elsewhere in China. Other Xinjiang Uighur relatives interviewed in Istanbul repeated stories of organ harvesting.

Tohti said she suspects her nieces and nephews may have been put in an orphanage set up by authorities in Xinjiang for the children of detained Uighurs. Experts say the orphanages are used to carry out a rigorous indoctrination programme aimed at eliminating the children's Uighur culture and identity."Prepared to fight to the end"

Chinese authorities say the camps are a policy against militancy and that there are legitimate reasons for Chinese authorities to be concerned about Uighur extremism. In 2009, ethnic riots in Urumqi, Xinjiang's capital, left more than 140 people dead and hundreds injured, as protesters attacked Chinese residents and burned buses.

In 2014, a terror attack was carried out on a market in Urumqi, killing 31 people. In response, the Chinese government intensified its surveillance and control of Uighurs. Yet Uighur Muslims have long faced cultural and political discrimination in China, which has led to widespread discontent and violence.

In a small shop in Istanbul, the blinds drawn for privacy, a smartly dressed Uighur man with closely cropped hair admitted that he had travelled to Syria in 2015 with a group of 50 to 60 Uighur men for military training by members of the Free Syrian Army (FSA).

The would-be fighter said they were taught how to use Kalashnikov rifles and fire artillery. He added the purpose of the six-month training camp in Syria was to return to Xinjiang and fight the Chinese Communist Party. The group planned to target military sites, and any Han Chinese working for the government was a legitimate target. With a calm expression, the man said they were "prepared to fight to the end."

So far, he said, the plan had run up against a brick wall, because several members of the group have been detained in Turkey and Europe. However, he said that he was still waiting for an opportunity to put it back into action.

Although it was impossible to independently verify his account, there have been other cases of Uighur groups that have trained with the FSA. Several hundred Uighurs have also reportedly joined the so-called Islamic State militant group.

German authorities do acknowledge possible "links" between Uighur separatist factions and the Afghan Taliban and al-Qaida, according to a confidential report compiled by the German Foreign Ministry late last year.

Punishing an entire population

However, under the guise of fighting terrorism, China's policy seems to punish an entire population, targeting the Uighur language, religion and culture and placing people under a tight-knit mesh of constant electronic surveillance.

And women like Tohti's two sisters – whose only "crime" was having too many children and applying for a passport – have been caught up in China's "war on terror".

"They will take you for no reason," one man asserted, whose wife's youngest brother was on the list. He spoke on condition of anonymity, fearing Chinese reprisal. But he was adamant that his brother-in-law, whom he described as a quiet student, had done nothing wrong.

"He was just normal," he said, adding that if the Chinese authorities in Xinjiang could imprison his bookish brother-in-law, no one was safe.

Naomi Conrad

© Deutsche Welle 2020