The red herring of 'Islamic human rights'

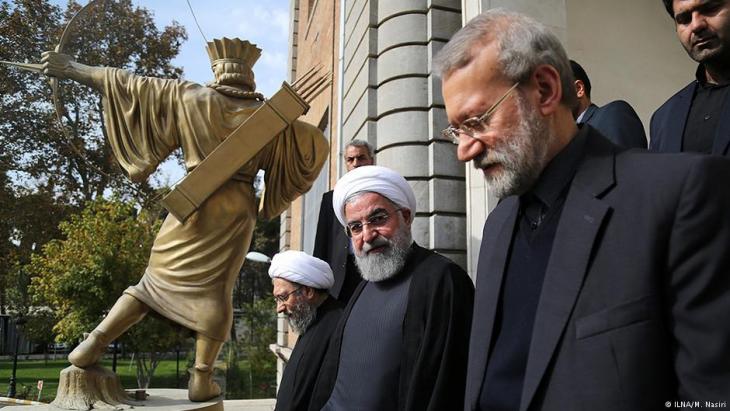

In international bodies, Mohammad Javad Larijani, head of the Iranian judiciary's Human Rights Committee, proudly defends the execution of "divine punishments" – including the amputation of thieves′ hands and death by stoning.

As I write these lines, there are people languishing in Iranian prisons just for the simple reason that they are followers of the Baha'i religion; others are there because they are accused of converting from Islam to Christianity or because they refused, as women, to wear the hijab. The Iranian laws used to prosecute and punish these people violate human rights, but they are justified by authorities who invoke Islamic law.

In 1990, the member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, which includes Iran, adopted the Cairo Declaration on Human Rights in Islam. If we view the declaration as the Muslim countries' own way of implementing the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, then there's no problem with that. But if these countries regard their declaration as a counter-proposal to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, then they have taken a wrong turn.

For if Muslims grant themselves the right to adopt their own human rights declaration on the basis of their religion, then they also need to grant this right to followers of other religions. The result would be a multitude of human rights declarations: one Jewish, one Buddhist and many more. It is obvious that this would not be compatible with universally valid and enforceable human rights.

Atheist states' reservations just as false

Officially atheist countries such as China, with its communist system, also do not accept the universal validity of human rights. In their view, human rights are founded in capitalist systems and their values, and are therefore incompatible with socialist ones.

But the argument is still wrong. Freedom of expression, for instance, does not contradict socialism and communism does not mean arbitrary rule. It is dictators, however, who understand and implement communism in this way. Thus either belief in God or the refusal to believe in God becomes a pretext for oppressing people.

The United Nations and other international organisations have so far focussed their attention on civil and political rights and have failed to pay sufficient attention to social and economic rights, the flouting of which is one of the causes of widespread poverty worldwide. This is another reason why human rights are not sufficiently respected in countries across the global South. This has contributed to undemocratic governments there disregarding their human rights obligations.

The inefficient functioning of the United Nations, particularly the Human Rights Council, has also prevented progress in the field of human rights over the past 60 years. When the UN Charter was drafted, there was too much optimism and too much certainty that states – not all, but most – enjoyed the support of their citizens and that they, as voters' representatives, would therefore investigate and eliminate cases of human rights violations.

For a globalisation of justice

But we have seen how governments in many cases are not elected representatives of their citizens and do not respond to the demands of the world public. So how can we expect countries that have repeatedly and persistently violated human rights to denounce human rights violations in other countries? Just remember that countries like Saudi Arabia and Syria sit on the Human Rights Council.

The main reason for the lack of sustained progress on human rights, however, is the ongoing impunity for those who violate them. The jurisdiction of the International Criminal Court is limited to its member countries. New ways of punishing offenders must therefore be sought. In cases where local courts are not able to provide justice, those countries committed to human rights must come to the aid of the victims of human rights violations and give them the opportunity to file complaints against their abusers.

In other words, it is time to talk about a globalisation of justice, meaning that those who violate human rights can be prosecuted in countries other than their own. Globalisation will only be considered a success if we succeed in globalising the judiciary.

Shirin Ebadi

© Deutsche Welle 2018