Press freedom under fire in Turkey

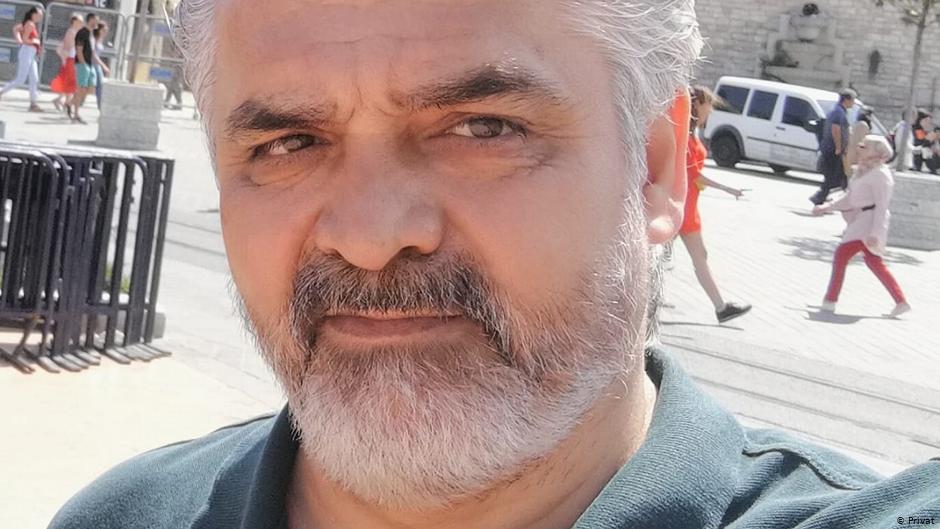

Threats, assault, or even armed attack – for journalists in Turkey the frequency of such incidents is increasing. One of the most recent cases occurred at the end of August in the western Turkish city of Balikesir: Levent Uysal, editor of the news site Yenigun, had just left his house when two men wearing helmets opened fire on him from a motorbike: they fired six shots before speeding off, Uysal reported. Apparently they had been waiting for him.

Uysal was lucky. Only one bullet hit its target, injuring his foot. Fortunately it didn't take long for Uysal to recover. For him, what was worse was that he felt abandoned by the authorities. Although the detectives in charge worked around the clock in an attempt to solve the assassination attempt, the governor of the city scarcely took any notice of the case, says Uysal. "He didn't even call me to convey his best wishes for my recovery. I would have expected that. I must admit that I have a suspicion why I was attacked – I hope it doesn't prove to be true."

Too critical in his reporting

Uysal had written about how representatives of the city administration of Balikesir were paying their relatives hefty pensions. He therefore assumes that his work was the main reason for the assassination: "My articles in recent months have been uncomfortable. They certainly won't have liked that. But it is my duty as a journalist to ask unpleasant questions, to uncover lies and to inform."

Harlem Desir, press freedom representative with the Organisation for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE), also called on the Turkish authorities to investigate the attack on Uysal and to bring those responsible to justice as soon as possible. "Violence against journalists is increasing at an alarming rate," says Desir. There have been six attacks on journalists since May. "We need to stop this trend and ensure a safe environment for journalists so that they can continue their work unhindered."

According to the BIA Media Monitoring Report, ten journalists were attacked in the first half of the year, three of whom were killed. Last week, the case of Umit Uzun – a journalist at the Demiroren News Agency (DHA) – drew the attention of the Turkish public: when he tried to report a traffic accident, policemen beat him up and handcuffed him. The non-governmental organisation Reporters Without Borders confirmed that Turkey is one of the most restrictive countries in the world when it comes to press freedom. The NGO ranks Turkey 157th out of 180 countries in its 2019 World Press Freedom Index.

The dangerous conditions and increasing attacks on journalists are also alarming international media organisations. Twenty international media houses, including Reporters Without Borders and the International Press Institute (IPI), which campaign for freedom of the press at an international level, have written to Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. In the joint letter, they condemn the increased attacks on journalists and call on Turkish politicians to bring those responsible to justice.

But the call has been ignored by the government alliance of the nationalist MHP and the Islamic-conservative AKP, says Erol Onderoglu, the Turkish representative of Reporters without Borders: "The attitude of the government and the authorities is irresponsible. After all, since the local elections on 31 March 2019, violence against journalists has continued to spread. It seems to me that no-one is interested in an adequate response." Police violence has also created a dangerous climate. "In Turkey, there is currently minimal protection for journalists' lives," warns Onderoglu.

Unemployment as an additional problem

In addition to physical violence, another existential problem affecting journalists in Turkey is unemployment. Like thousands of his colleagues, Uysal also has to contend with an economic downturn. When his newspaper was close to bankruptcy, he decided to only publish online. "There is hardly any support from my community, so we can barely keep our heads above water," he complains.

According to figures from the Turkish Statistics Institute (TUIK), journalists were – after social workers – the second occupational group most affected by unemployment in 2018. In just one year, the number of unemployed journalists rose by 4.7 percentage points to 23.8 percent. It is a sector that is dominated by mushrooming media cartels.

The attempted coup in July 2016 was followed by the mass closure of media and press houses. Moreover, the situation has not been helped by the weakening of the Turkish trade unions. And the result? Plurality is falling by the wayside.

Deger Akal

© Deutsche Welle/Qantara.de 2019