Decades Later, Malcolm X's Legacy Lives On

In February, Americans celebrated Black History Month. It is also during this month in 1965 that Malcolm X, an African American Muslim minister and civil rights activist, died. His legacy is important for Muslims and non-Muslims alike – and one that has influenced many Muslim Americans, including myself.

One cannot reflect on the condition of African American communities in the United States without being confronted by the intensity of black suffering. In the world's richest nation, poverty rates are higher among black Americans than any other group.

Despite the historic fact of having a black president in the White House, black Americans are often politically marginalised. For instance, there are no African Americans in the US Senate. When it comes to racial injustice, we are still at the beginning of America's redemption.

Social, cultural and structural adversity

The story of Malcolm X's life is well-known. He was born to parents who were civil rights activists, but after his father's death and his mother's hospitalisation in a mental institution, he became embroiled in a life of petty crime.

He then went to prison and found religion, id

entity and purpose in the form of the Nation of Islam (NOI), a Muslim movement that emphasised black liberation and black separation from whites. Malcolm's transformation from a small-time hustler to a nationally renowned black Muslim is in itself a story of triumph in the face of social, cultural and structural adversity.

The most outstanding aspect of Malcolm X's life is this transformational power that he personified. He realised that no black man would ever be truly free of racial subordination until there was a collective escape from the tyranny of racism.

Sadly, under the influence of NOI, Malcolm X advocated racial segregation, and demonised white people as essentially evil. He preached a separatist nationalism as a way to restore dignity to black people.

Later, he began to sense the injustice in his own ideology. I find Malcolm X's ability for critical introspection – even when facing extreme hostility and adversity from the outside – inspirational. He apprehended the moral failings of his movement. In 1964, disillusioned with NOI, he left it in search of another path.

Encounter with a universal ethos

That year he went on the haj, the Muslim pilgrimage to Mecca, where he encountered the racial diversity within Islam for the first time. He saw a remarkable absence of racial prejudice in the ways that Muslims interacted with each other, an experience that taught Malcolm that people of different races could coexist. After this decisive encounter with a universal ethos, Malcolm X (who began calling himself El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz) sought to balance his Afro-centric political worldview with his belief in a universal Islam.

El-Shabazz returned to America a transformed individual. Even though he was still engaged in the struggle for the liberation of black people, his angry racial rhetoric and posturing were replaced with a universal quest for justice. He now believed that he could be a partner with non-Muslims and white people in an effort to construct an America and a world free from racial hatred and domination, a message he sought to spread by speaking on numerous college campuses. Unfortunately, El-Shabazz was assassinated before his 40th birthday.

El-Shabazz is a hero to millions of people in America and the world, while remaining a special inspiration to African Americans. He taught them how to stand up for themselves with pride and dignity. For Muslims, he is viewed as a bridge that spiritually connected America to the Muslim world. For American Muslims, he is one of the founding fathers of their nation.

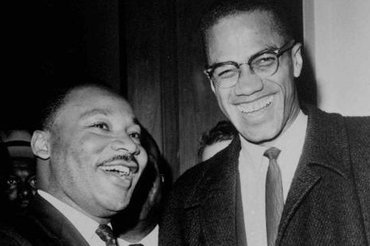

He may have come on the scene two centuries after its founding, but along with Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. and President Obama, he has made the cardinal principle of this nation – that all men are created equal – more believable.

Muqtedar Khan

© Common Ground News Service 2012

Dr Muqtedar Khan is Associate Professor at the University of Delaware and a Fellow of the Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. His website is www.ijtihad.org.