Hope must go on

So the negotiations are going into extra time after all. Up until a few days before the deadline of 20 July, both sides had publicly denied even thinking about extending the talks, let alone discussing such a thing. Nevertheless, it comes as no surprise that Iran and the P5+1 group have decided to continue their talks until 24 November 2014. Right from the word go, observers had expressed doubts that an acceptable solution for both sides could be found at the first attempt, after years of disagreement.

Does that mean the extension is no reason for concern? Not quite. On the one hand, it is undoubtedly positive that both sides are making serious efforts to reach an agreement. The High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs & Security Policy, Catherine Ashton, who led the talks on behalf of the P5+1 group, and the Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammed Javad Zarif emphasised after every round how "positive" and "constructive" the talks had been. Before the decision to extend the deadline, Zarif and his US colleague John Kerry were also agreed that "significant progress" had been made.

Call for restrictions

On the other hand, the differences remain considerable and a solution is unlikely to get simpler as time goes on. Yet while the issues to be resolved are doubtlessly complex, they are not impossibly so. This much is clear: the biggest disputed points are the heavy water reactor at Arak, the timeline for the removal of sanctions and uranium enrichment.

Whereas it has emerged that the Iranians are prepared to modify the half-finished Arak reactor so that it produces less plutonium, there are still significant differences on the other issues.

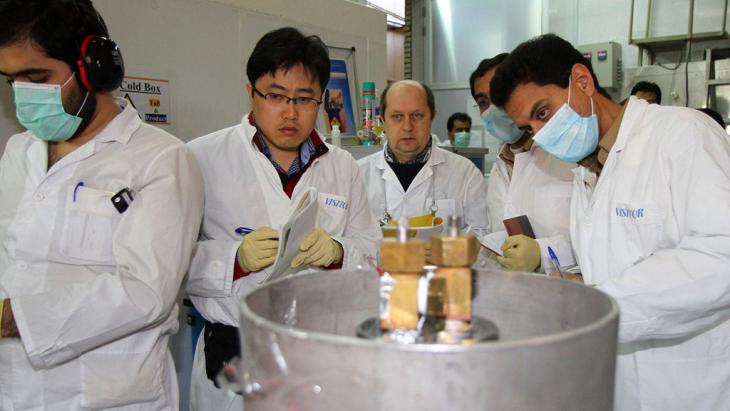

In terms of uranium enrichment, the West wants Iran to commit to reducing its centrifuges from the current 19,000 in the Natanz and Fordo facilities – around half of which are in operation – to a few thousand. The aim is to restrict its capacity for enrichment, or to lengthen the period required to produce the highly enriched uranium required to make nuclear weapons. The West also wants to limit research on more efficient centrifuges. Iran rejects constraints of this type.

Scepticism among Iranian hardliners

In a 15 July interview with the "New York Times", Zarif gave a rare insight into the Iranian negotiation position. Teheran, he revealed, rejects the demolition of centrifuges but has offered to freeze uranium enrichment at the current level for three to seven years. The low-enriched uranium required for energy production and research purposes would then be quickly transformed into fuel rods – all under strict international supervision. Essentially, this would be an extension of the interim agreement.

And this will remain the basis for negotiations in the coming four months. The treaty signed in Geneva on 24 November 2013 should have expired on 20 July; however, as agreed shortly before the deadline, it will now continue until the first anniversary of its signing. Until then, the halt on construction on Arak remains in place. Iran has also agreed not to enrich uranium to more than five per cent and to transform more highly enriched material into fuel rods. In return, Iran receives 2.8 billion dollars of its frozen oil income.

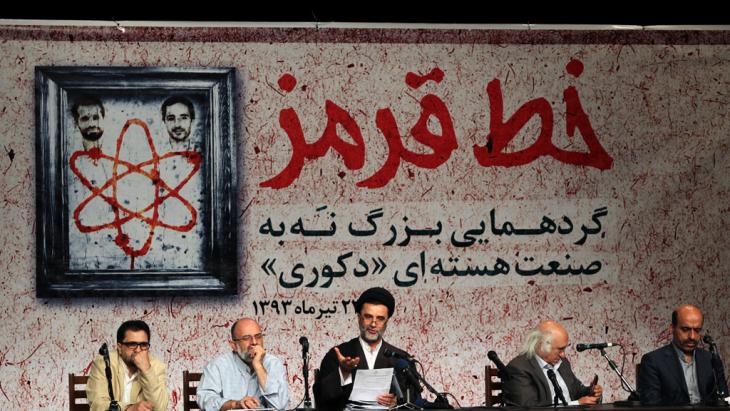

Iran's sceptical hardliners will examine the agreement thoroughly. They reject concessions to the West and are doing their best to sink the negotiations. They have not succeeded as yet, mainly due to President Hassan Rouhani and his foreign minister's good standing with the Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. The latter has made sceptical statements on the negotiations, but has nevertheless held back the hardliners. When their criticism gets too extreme, leading conservatives regularly leap to Rouhani's defence.

Yet although Khamenei supports the talks in principle, his public statements are frequently puzzling. In a speech on 8 July, for instance, he said that on the issue of enrichment capacity, Iranian experts said that the country would need some 190,000 Separative Work Units (SWU) to cover its needs, "not in the coming two or five years," but in the long term. This corresponds to about 60,000 centrifuges of the old type currently in operation in Iran. That set off alarm bells in the West, of course. In the middle of the most tense phase of the talks on a limitation of uranium enrichment, the statement was not helpful.

Resistance on the horizon

Another unhelpful occurrence was a letter sent to President Barack Obama on 10 July by the two leading members of the US House Foreign Affairs Committee, Ed Royce and Eliot Engel. In the letter, signed by 342 congress members, they emphasise that the concept of an exclusively defined "nuclear-related" sanction on Iran does not exist in U.S. law and that they would only agree to the removal of the trade and financial sanctions against Iran if Teheran were also to make concessions on human rights, terrorism and its rockets programme.

Should the members of congress retain this stance, the US government will have difficulties revoking many of the penal measures. Precisely that, however, is the condition for Teheran's concessions. The letter is also likely to strengthen all those in Iran who accuse the USA of merely using the nuclear issue as leverage to force Iran to its knees. Look at this, they can now say, if we give in on this issue, the USA will bring up other questions – like the rocket programme – to bully us into submission.

Thus, further resistance looms both in Teheran and in Washington. For this reason alone, the negotiation partners should not take too much time. Despite the complexity of the material, the options for both sides have been clear for some time. The only open question, ultimately, is how much each side is willing to concede. A failure of the talks is in nobody's interest, because a new initiative would be unlikely for quite some time. Instead, the tensions are likely to increase markedly. Any deal would have to be very bad to be worse than no deal at all.

Ulrich von Schwerin

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de