Escape at all costs

When he left his tent towards evening on Christmas Day, the young man from Burkina Faso wondered where he would be the next morning. Would he have made it to Europe? And ended up in a refugee camp somewhere in Melilla? Maybe he would be on the streets. Or might his journey end at the high border fences, where he would be snatched by the Moroccan police? These thoughts may have been running through his mind as he set off to conquer the border installations of Melilla with a large group of refugees from sub-Saharan Africa.

When a small mission from Misereor met him a short time later, the twenty-year-old was in a wheelchair, both of his legs broken. The people from the Catholic aid organisation documented the case, but they didn’t take his name – and they no more than hinted at other features that might identify him.

The fact that he is currently living with many other stranded migrants in the mountains near Nador is the only other thing we know about him. And that he almost made it. He got past two fences, with their barbed wire, cameras and sensors, and had climbed the third before the six-metre jump down sealed his fate.

Two unremarkable doors – back to Morocco

The Guardia Civil left him lying on Spanish soil for five hours, or so Misereor would later report. It’s the Spanish border force’s way of ensuring that when the failed refugee tells his story, it serves as a warning – to all those who want to try the same thing. Only later did the officials pick him up and carry him through two unremarkable doors that led back through the fence. Back to Morocco.

Why does this man have no name? Perhaps because he also stands for so many others to whom the same thing has happened. And his name, his experiences would make his fate an individual case, lifting him out of the collectively-experienced violence. He also doesn’t want to give his name, he says, because he’s afraid his family in Burkina Faso might then see how he is living in Morocco. And that he didn't make it to Europe.

His shame is understandable: he is camping in a forest in the mountains with others who share his fate. They have built accommodation for themselves out of tents and plastic sheeting. With no running water, food, proper blankets or medical care, the people who have fled are exposed to all weathers out in the open – men, women, children, even babies. Sometimes units from the Moroccan police arrive, give the inhabitants a beating and lay waste to the whole encampment. This behaviour is another tactic intended to put others off and is – at least tacitly – approved by the European Union as a necessary evil.

The routes are shifting

Just two months previously, Spain was condemned by the European Court of Human Rights for a similar "hot expulsion", which is their term for what happened to the man with the broken legs. But it doesn’t seem to have made too great an impression on the Spanish government. Firstly, they are also acting on behalf of the EU, which will do anything to stop more people coming to Europe.

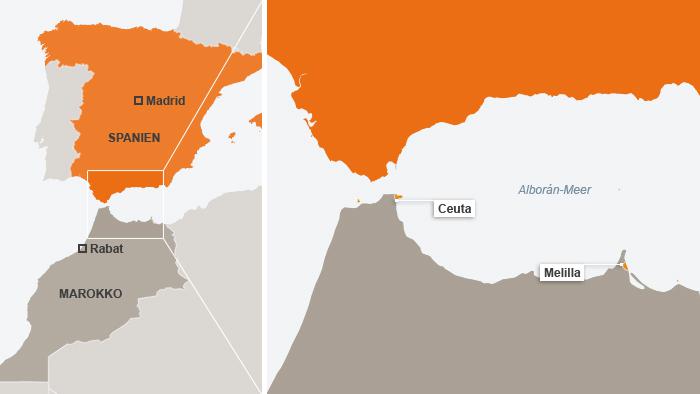

Secondly, Spain has been very successful in combatting migrants using these methods in recent years. In 2014, fewer than 2000 people made it across the borders into the exclaves of Ceuta and Melilla, or across the Strait of Gibraltar and onto the Spanish mainland. The route through the western Mediterranean via Morocco has long been regarded as closed. Many are therefore choosing the alternative route via Libya. But this is starting to change.

In the last year, the number of people coming via Spain rose to over 20,000. Compared with the central Mediterranean route via Libya to Italy, that still isn’t a huge number: with almost 120,000 migrants, six times as many make the crossing there.[embed:render:embedded:node:31167]But the numbers show a trend: the routes are changing again. Arrivals in Italy have decreased by a third in the last year, but they have increased in Spain. More than three times as many have arrived there as in the previous year. The fact that the refugee routes are shifting is due to many changes that the EU – and in particular Italy – have made in the past year.

These include the fact that the European Union has blocked the central Mediterranean route at its hub in Agadez, Niger. Since then, many migrants from countries in sub-Saharan Africa have been looking for new ways in, avoiding the western route via Algeria and Morocco. Around 40,000 sub-Saharan migrants are thus stranded in Morocco, according to Misereor, waiting for their crossing.

Destination Europe – whatever the cost

But another measure, taken single-handedly by Italy, may well have been even more effective. Last summer the government reached the end of its tether and, in an act of desperation, paid militias to operate as coastguards and tow refugee boats back to the coast of Libya. It was a last-ditch attempt to stop the rush of people crowding the Italian coasts, which had hit a new record high.

The situation was extreme, the government in a panic. In just four days in June, 12,000 people had landed in Italian harbours. Desperate appeals for solidarity from other member states fell on deaf ears. And so the Italians abruptly sealed off the central Mediterranean.

Since the central route has been closed, more people have gone back to trying their luck against the high fences and razor wire of Ceuta and Melilla. No matter that this is an almost impossible task. That shows one thing: people fleeing will not be stopped by closing borders. Even the route out of Libya, closed by armed militias, has become more porous again over the last few weeks, despite being more dangerous than ever, with 400 people drowned in the first weeks of 2018.

"Migration will keep finding a way, no matter what the cost," says Martin Brockelmann-Simon, managing director of Misereor, who met the young man in a wheelchair from Burkina Faso in Morocco. Despite having broken both legs on the fences of Melilla, he agrees. He is certain: "It just wasn’t my day. But my day will come!"

It would be good to be able to link a name to his fate – and a face. Nameless, the people stranded in Morocco remain an anonymous mass. And that makes it even easier for us to forget what they are going through there every day.

Susanne Kaiser

© Qantara.de 2018

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin