Echoes of a shared past

When war broke out between Iran and Iraq in 1980, Persian and Arabic cultures became divided by a seemingly unbridgeable chasm. In the Islamic Republic of Iran, established after the revolution of 1979, the new government defined the conflict as one between the Arab and Persian worlds. The idea that music could form a common ground between the two peoples became almost inconceivable.

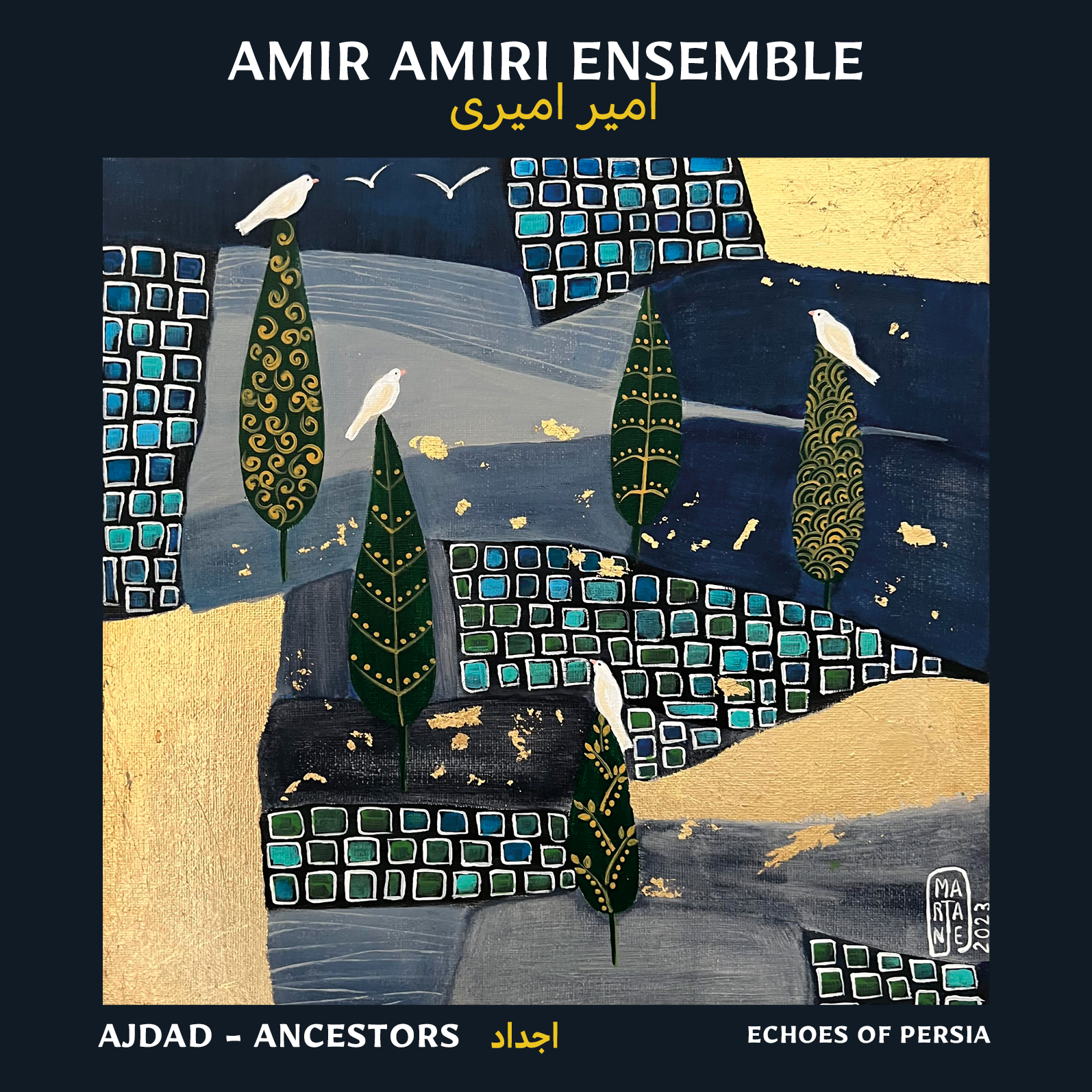

The Amir Amiri Ensemble's release "Ajdad - Ancestors: Echoes of Persia" does more than dive into the history of Iranian music, as its title implies. The album also looks forward by bridging the gap between Iranian and Arabic music to create something new.

Amir Amiri's father was raised in northern Iran, bordering Iraq, and had long been exposed to Arabic music. In turn, he passed this interest, and a willingness to look beyond the confines of his own country, to his son.

In Iran after the revolution, not only Arabic music, but music in general was criminalised. As a young man living in Tehran, Amiri had to smuggle his santur, an ancient 72-string instrument, through the streets wrapped in a blanket when he travelled to his lessons.

It was only in 1996, when he immigrated to Montreal, Canada, that Amiri was able to begin expanding his musical boundaries. One of the obstacles he sought to overcome was the limitations of the santur, whose tuning made it difficult to play certain kinds of music. In Canada, he met Mohsen Behrad, who had created a santur with moveable bridges, giving Amiri the freedom to play a variety of musical traditions.

Amiri also met a range of musicians from across the Arab world, which allowed him to begin bridging the two musical traditions that had been severed for decades. His ensemble is drawn from an ever-expanding pool of Arabic and Iranian musicians in Canada, playing instruments that represent a cross-section of those played in Iran and across the Middle East.

Omar Abu Afach is a violin/viola player who immigrated to Canada from Syria in 2015; Oud player Abdul-Wahab Kayyali is a Palestinian born in Lebanon who works out of Jordan and Montreal; Reza Abaee plays Ghaychack (a Persian violin) and currently lives in Montreal; and Hamin Honari is an Iranian Canadian percussionist.

In each of the songs, Amiri and his ensemble explore the variety of musical patterns and forms of both Persian and Arabic classical music, taking listeners to the heart of both traditions. Many of the album's tracks are either traditional dances or are built around the framework of classical Persian music, alongside a few original compositions.

The meditative "Yadegar Doust" (Memory of Friends) is a piece Amiri wrote about his struggle to adapt to living in a new country and missing the people he left behind. For an instrumental, it communicates the complex emotions of the subject remarkably clearly—we hear both the sense of loss and hope for a new future.

Amiri explorations go beyond Arabic music—"Homayoun" (Royal) is influenced by Turkish music, while "Ragseh Sama" (Sama Dance) is shaped by Kurdish traditions. Given the marginalisation of Kurds across the Middle East and in Iran, his engagement with their musical traditions in his compositions underscores a desire to break down the boundaries separating the region's cultures.

The Amir Amiri Ensemble have attempted to build the first spires of a new musical bridge between Iran and the Arab world, demonstrating that the two musical traditions, and people, have much in common.

Despite the Iranian government's efforts to sever its people from their cultural traditions—particularly the rich diversity of their music—artists like Amir Amiri and recordings like "Ajdad" ensure that this heritage can continue to thrive and grow.

© Qantara