Orientalising Orientalism

The way leading to the Berghain club in Berlin's Friedrichshain borough is messy this evening. It is a narrow, muddy path, at the end of which a huge concrete structure rises impressively into the black night. Berghain, long since well known outside Berlin, is one of the world's archetypal techno clubs. Once a power station, the building is now synonymous with excess, darkrooms and thumping bass lines.

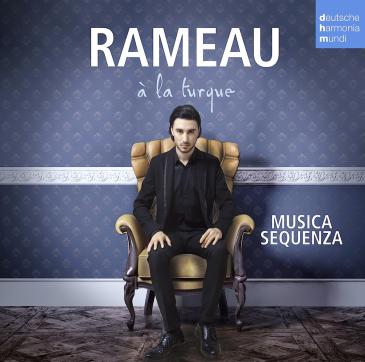

Yet in a place where techno beats and house music would normally thump out from the giant sound system, less familiar sounds are on the programme this evening. The chamber music ensemble Musica Sequenza, led by the Turkish bassoonist Burak Ozdemir, has invited the public to enjoy a musical crossover experience. The performance of the night is "Rameau a la Turque", a fusion of parts of the ballet opera "Les Indes Galantes" by the French Baroque composer Jean-Philipe Rameau with compositions by the Ottoman court musician Tanburi Mustafa Cavus, all arranged by Ozdemir himself.

The spotlight goes on and the nasal sound of the bassoon fills the air, accompanied by harpsichord and violin, at first hesitant, then growing more and more confident. The atmosphere is sacred and at the same time intimate. Three of the ensemble's ten musicians play Oriental instruments: the ney (a reed flute), the qanun (an Oriental zither) and the rhythm instrument kudum. In Ozdemir's fusion arrangement, his bassoon joins the ney to play Oriental melodies, or Oriental rhythms form the background to the Western Baroque court dance.

A Baroque hipster a la Turque

Ozdemir has styled himself as quite the Baroque hipster, his long, dark hair in a loose bun, a bow tie, glittery white shirt, blazer, knickerbockers and white socks. Light-footed and with minimal arm movements, he conducts the ensemble grouped around him, the other musicians dressed entirely in black.

On stage, he comes across as a dreamy bird of paradise, yet in conversation he is attentive and focused. Born in 1983, Ozdemir has a CV that is best described as "impressive" – music conservatory in Istanbul, studied at the University of the Arts in Berlin, PhD from the Juilliard School in New York and all kinds of projects, including one with the choreographer Sasha Walz. "It all developed organically," says Ozdemir, whose father was a professor of composition at the Istanbul music conservatory.

Where does a Baroque bassoonist get such a passion for fusion, for performing in unusual locations? "That's always been my focus," he says. He has always been intrigued by crossover: mixtures of electronic sounds and Baroque music, new interpretations like Vivaldi's "Four Seasons" or Bach's "Silent Cantata", Pergolesi with modern opera ...

Ozdemir loves to play with styles and epochs. His latest project "Rameau a la Turque" was inspired by digging deeper into his own origins. His family is one of the few that has lived in Istanbul for many generations.

"I discovered the many French traces in Istanbul; street names and street signs. French was my grandparents' language and my father learned through French when he studied at the conservatory. People in Istanbul followed Paris fashions very attentively, and at the same time there are Oriental motifs in eighteenth-century European painting," he says with enthusiasm. And so the idea to arrange the Oriental kudum, ney and qanun alongside Western Baroque instruments was born.

In Ozdemir's selected extract, "Le Turc genereux" (the generous Turk) from Rameau's Baroque opera, a merciful pasha grants freedom to a Christian woman he admires and the slave to whom her heart belongs. This is an example of "exotic love" from this era and a motif taken up again some 90 years later by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart in his singspiel "Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail".

Interweaving Western Baroque with Ottoman court music

By combining compositions by Rameau and his contemporary Tanburi Mustafa Cavus, who died in 1770, Ozdemir does more than just revive two almost forgotten composers and their works. By interweaving Western Baroque and Ottoman court music, he could be said to be orientalising Rameau's Orientalism – tongue firmly in cheek, of course.

The contemporaries Rameau and Cavus came from two different musical traditions. Whereas French musical training was highly developed, at the Ottoman courts it was subject to strict regulations, only escaping from this rigid corset with Munir Nurettin Selcuk around 1900. The music of the Ottoman seraglio had to consist of a trio of ney, qanun and kudum, whereas Rameau could choose from any number of instruments, according to the sound he wanted to create.

"The biggest difference" says Ozdemir, "is that Western music is polyphonic, consisting of several melodic lines, whereas Ottoman music has a single voice." Yet he also sees common features. For example, the phrases and motifs in French Baroque were much shorter than they were in the later Romantic period. Short phrasing is also a feature of Ottoman music.

"Another shared factor is that there is no information given in Baroque music as to how the instruments have to be tuned. There are different tuning systems such as Valotti or Werckmeister. We have something comparable in Oriental music with the makams, the melody types, like ussak or nihavend."

Numerous challenges for all musicians involved

Working on the pieces presented the ensemble with a number of challenges. For example, the Oriental instrument-players had to get used to polyphonic structure, pauses and the right cues. For the players of Western instruments, on the other hand, it was a challenge to work out the right quarter tones and get used to 9/8 rhythms. "But I have good, solid musicians," says Ozdemir of his ensemble.

The members of Musica Sequenza play on reconstructions of original Baroque instruments. For those used to digital sounds, the tone is slightly dull to begin with, yet over time, it develops warmth and depth, in the quieter pieces in particular. Whereas modern instruments have steel strings, eighteenth-century instruments use gut. The violin has a narrower body and there is more pressure on the bow, which creates a more focused sound than modern instruments.

The wind instruments, in contrast, have fewer holes than today's and are therefore simpler and less automated. "The musicians have to do more. They're more flexible in timbre, which makes them similar to the ney," says Ozdemir.

"Rameau a la Turque" is a musical jewel by a sensitive young artist, whose previous work has rightly been praised by the "New York Times" as "more than energetic" – and from whom we are sure to hear more in the future.

Ceyda Nurtsch

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire