What the Arab world can learn from Indonesia

Currently many Arab states are attempting to cement the links, by force if necessary, between the state, creed and civil society. This has been the top priority for rulers in the region ever since the Arab Spring broke out in the Middle East in 2011. The mass uprisings altered the political landscape in the Arab majority world and sent dictatorial regimes a clear message: if they wanted to remain in power, they would need to discover a middle ground, reaching political decisions that benefit the common good.

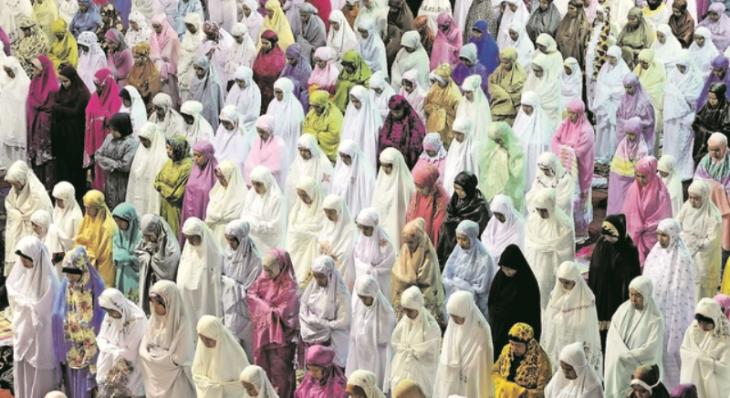

Indonesia – an enormous archipelago of a country in Southeast Asia – is the world’s fourth most-populous state and the largest Muslim-majority nation. Yet many are unaware that, regardless of the size of its Muslim population, Indonesiaʹs state religion is not Islam. It may seem unbelievable, but Indonesia officially recognises five official religions: Islam, Christianity (Roman Catholicism and Protestantism), Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism. Since it achieved its independence from the Netherlands in 1945, Indonesia has become a democracy characterised by cultural diversity and a sensible interpretation of Islam.

In an attempt to legitimise their authoritarian regimes, rulers of the Arab world generally contend that their tradition of government was bequeathed by the Prophet Muhammad and that this convoluted blend of religion and the state is inseparable and unquestionable.

"Pancasila": for peaceful co-existence

While Islam is the state religion of most countries in the Arab world, with constitutions based on the Koran, Indonesia is based on a nationalist ideology – Pancasila – which advocates secular, democratic and nationalist principles.

Yet, how can Pancasila, a nationalist ideology, help promote social inclusion and integration? The five principles of Indonesian politics are, indeed, poles apart from Arab nationalism. While Arab nationalism is based on a shared ethnicity, language and culture, Indonesian nationalism is precisely the opposite. It is multi-ethnic, multicultural and multilingual – all indicators of progressive nationalism. Pancasila is based on the following:

belief in the one and only God (Article 29 of Indonesian Constitution mentions there is no specific god of any religion who holds superior status);

a just and civilised humanity (cultural and religious freedom twinned with mutual respect);

a unified Indonesia (multi-ethnic, multicultural and multilingual);

democracy, led by the wisdom of the peopleʹs representatives (Indonesia is democratic, in contrast to the sparsely populated Gulf states, which are still dominated by religious autocracies);

social justice for all Indonesians (irrespective of ethnicity and religion).Apostasy, blasphemy and social ostracisation

According to conservative Islamic rituals in the Arab majority world, non-Muslim men must convert to Islam if they wish to marry a Muslim woman. If anyone wants to renounce Islam and embrace another faith, it is considered apostasy. Those in question face social ostracisation and, in some cases, harsh punishment. Openly practicing other religions is considered blasphemy and even constructive criticism of Islam may be viewed as a threat to the state and its religion.

In Indonesia things are different: interfaith marriages call for one partner to ceremoniously convert to one of the six acknowledged religious creeds. A Muslim man/woman can convert to their partner’s faith without violating any law, because Indonesia doesn’t have a law specifically devoted to apostasy.

Indonesia does have a blasphemy law, but it is very different from the Arab version. Article 156 (a) of Indonesian Penal Code prescribes a penalty of up to five years imprisonment for expressions or actions in public that have "the character of being at enmity with, abusing or staining a religion adhered to in Indonesia", or are committed "with the intention to prevent a person to adhere to any religion based on the belief of the almighty God".

Indonesia therefore protects all religions on the one hand, while punishing the proselytisation of atheism – a situation that could still change in the future.

Indonesiaʹs progressive Muslim thinkers

Indonesia has generated some extraordinary progressive Muslim thinker-activists, men as miscellaneous as Tan Malaka, Haji Misbach, Tjokroaminoto, Agus Salim, Mohamad Natsir, Kartosuwiryo, Nurcholish Madjid, Dawam Rahardjo, Kuntowijoyo and Abdurrahman Wahid.

Apart from a few exceptions, their work has yet to be translated into Arabic or English, which is one reason their comprehensive philosophy has had little impact on other regions of the world. Were this literature to be made available to the Arab world, it would undoubtedly have a positive influence on its populations and political systems.

The influence of Islamist groups has increased throughout the Middle East because they are looked upon as an insignia of resistance against dictatorial regimes and extended a status of being "upright and untainted". In Indonesia, religious associations have shaped progressive intelligentsias, who have upheld the perception that religion and democracy are compatible.

Being linked to mass religious organisation, these public intellectuals have played a crucial role in Indonesia’s democratisation procedure. Their participation in political society has helped legitimise a democratic society and reinforced pro-democratic coalitions.

Indonesia has always been secular and progressive when it comes to education. The Islamic schools in Indonesia, for instance, use Islam as a foundation, but mostly in combination with progressive nationalism. Moreover, Indonesian Islam is known for its syncretic occult rituals, which stem from Javan Hinduism. Islamic practices and customs in Indonesia are characterised by traces of this religious fusion.

Tolerance and openness to different opinions

The Indonesian version of Islam is valued for its lively rational discourse. It is noticeably open to different opinions and religious diversity. Liberal and reformist trends, such as Indonesia’s Muslim feminist movements, are the most vigorous. In the few secular areas within the Arab world, they are well-known for having helped establish a spirited alliance of women’s groups and individual activists taking up numerous women’s issues from grassroots to the legislative level. For the most part, however, Muslim feminist movements in the Arab world still tend to be close to with the ruling elite.

We have to concede that time and circumstances fluctuate, political philosophies vary, structures of economic elites contrast, arrays of civil-military relations vary, as do corresponding positions within the international system of power and authority, all to greater or lesser scopes. Yet, if reformers in the Arab world want to generate long-lasting positive change, then emulating some of what has actually worked in Indonesia would be a good place to start.

Abhishek Mohanty

© Mashreq Politics & Culture Journal (MPC) 2018