Ever optimistic

Elegantly-dressed Mazhar Zumrut does not want to converse with us in the asylum centre's community room: he doesn't trust the others living there. "They could spy on me," he whispers. He is mistrustful and feels persecuted and spied upon, even in supposedly safe Germany.

Yet, he is doing better in the German countryside on the border of North-Rhine Westphalia. He has settled in to life in Germany, in his small, brightly-painted room. He says he has no other choice.

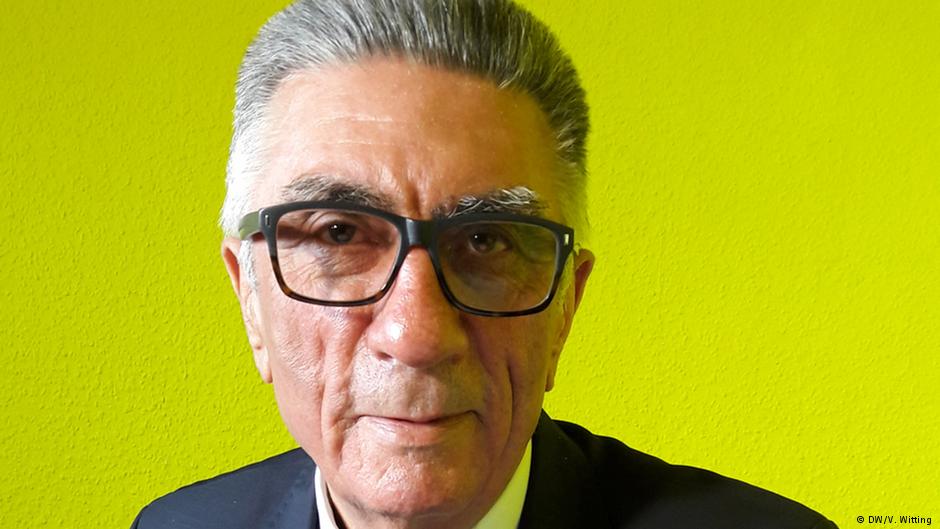

Mazhar Zumrut: fighting for political asylum

Mazhar Zumrut has survived an odyssey. He first fled to Syria and then Iraq before arriving in Germany in May. He officially applied for political asylum on 20 May. He says he feared for his life in a country in which repression and despotism have spread under President Recep Tayyip Erdogan: "the Turkey I fled is like Germany in 1933," says Zumrut. Now, he is pinning all his hopes on Germany. "The rule of law is still respected here."

As a Kurd living in Diyarbakir, he experienced injustice every day. He was cursed as a traitor and a terrorist. When police broke into his house last summer he knew it was time to leave. There has been a warrant out for Mazhar Zumrut's arrest ever since - forcing him to go into hiding, separated from his wife. Zumrut is accused of being a member of the outlawed militant group, PKK (Kurdistan Workers' Party).

The 64-year-old Zumrut, a former civil servant in the Ministry of Employment, denies the accusation. He says he is simply a member of the Kurdish BDP (Peace and Democracy Party), a local branch of the pro-Kurdish HDP (Peoples' Democratic Party) with seats in Turkey's parliament – the representatives of which were summarily arrested last month. And that is exactly what he told Germany's Federal Office for Migration and Refugees (BAMF).

Record numbers of Turkish asylum seekers

Over the last several months, the agency has registered skyrocketing numbers of Turkish citizens applying for political asylum. Especially in the wake of the failed coup on 15 July and the ″purge″ that the Erdogan government has been engaged in since then.

According to BAMF, 4,437 asylum applications were submitted between January and October alone. By now that number likely exceeds 5,000. Most applicants say that they are members of Turkey's minority Kurdish community. In 2015, the agency says that it only received 1,767 such applications.

The German government and the foreign ministry are exhibiting solidarity with oppressed Turks. Recently, the minister of state at the foreign ministry, Michael Roth, explained in an interview: "Critics in Turkey should know that the German government stands with them in solidarity. Politically persecuted persons are free to apply for asylum here."

Last hope: Germany

For Zumrut, such declarations are a great relief, and give him hope. "Germany is a country of laws. I don't think it will turn me over to the fascists in Turkey."

But Mazhar Zumrut isn't just worried about his own fate. He shows us pictures from happier days in Eastern Anatolia, in Diyarbakir. Together with his wife, an artist, he smiles broadly into the camera. "I miss her, I want her to come to Germany, too. But my wife has had to go underground as well."

It is difficult to maintain contact with her as Zumrut fears his phone calls will be listened to by Turkish authorities.

The waiting has taken a toll on his nerves. A German course, which he attends daily, offers a bit of distraction. He says that part of the reason he came to Germany has to do with the fact that he had some German in school and then later at university. "But that was 40 years ago. It is difficult."

Zumrut is not letting that get him down, however, he is fully engaged in his German class.

Nagging uncertainty

Yet, sentimental feelings come in waves. His wife: abandoned. His future: unclear. His way home: blocked. "Until the rights of Kurds are finally anchored in the constitution, there is no way that I can go back to Turkey," he summarises.

A decision on his asylum application is due soon. It is said that hope is the last thing to die. But statistics, says Zumrut, are rather sobering. This year, only about seven percent of those Turks seeking asylum in Germany have received it.

If he is unlucky, the elegant man from Diyarbakir says that he will have no choice but to go into hiding once again. Every morning he goes to the post box in hopes of finding a confirmation letter with the words: ′Your request for asylum has been granted′.

Volker Witting

© Deutsche Welle 2016