Yearning for home

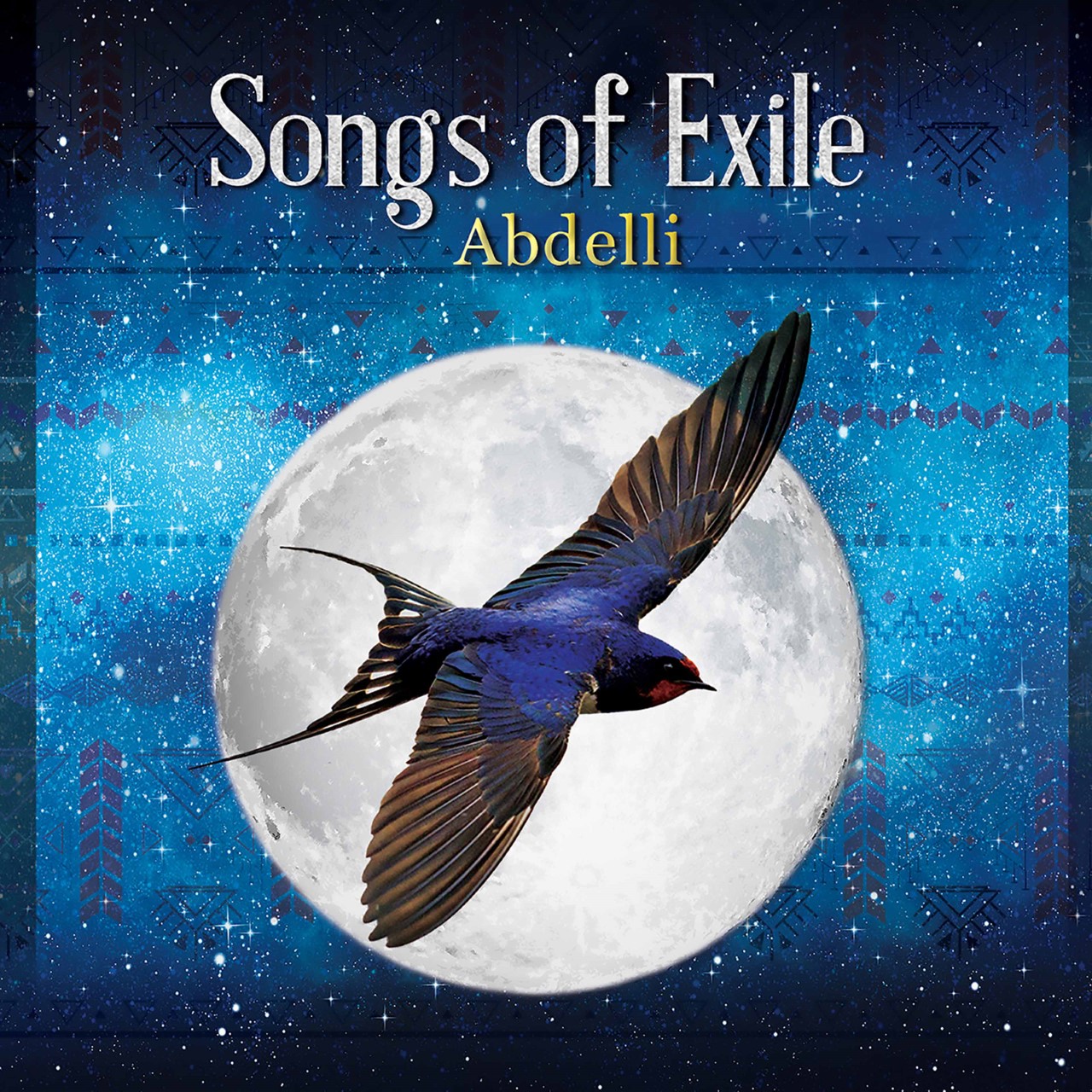

Songs of Exile, on the ARC Music label, is the latest release from Abderrahmane Abdelli. While originally from Algeria, Abdelli left his birth country in 1986 and has lived the life of an exile ever since. However, reading his biography, one could almost say he was born a refugee.

While his mother was pregnant with him during the Algerian War of Independence, the village his parents lived in was destroyed by the French air force. Within the first year of his life his family was forced to move again, finally settling in Dellys, a town on the Mediterranean Sea.

While he began his music career in this town – he performed his first concert at the age of 16 as part of the local Independence celebrations, and released his first album in 1986 (Ayem-yema) – politics and society were stacked against his becoming a musician in his native Algeria. He, along with other musicians from the Kabyle region, were forbidden from singing in their native Berber language.

In spite of the fact that over 50% of the country's population speaks Berber, it took until 2016 for it to be recognised in Algeria's constitution as an official language. In fact Algerian governments treated Berber dialects with the same disdain they reserved for French, going so far as to refuse to refer to it as Berber because that word undermined national unity.

Stateless in Belgium

All of which explains how Abdelli found himself a stateless person in Belgium in the 1980s. In some ways this proved to be a fortuitous event, as it was in Brussels his international musical career began. Here he met Henri Bernard, another of the world's displaced people, who became his champion and started him on the road to international success which has included touring with Peter Gabriel and playing international festivals such as the UK's WOMAD (World Of Music and Dance).

Although Bernard died in 2008, Songs of Exile honours his memory just as much as it pays tribute to displaced people all over the world. While Abdelli began working on the tracks for this release shortly after he completed his last recording, Destiny, in 2008, he put them aside shortly afterwards.

Now he has now reworked them, using the original barebone vocals with mandola accompaniment to reach out to musicians around the world for their collaboration on creating a fitting tribute to his friend.

Each of the thirteen songs on this recording are more than just personal songs in praise of a friend. Nor are they simply songs dealing with his own story of exile.

While they would still have been powerful in that context, Abdelli has eschewed this easy path and opted to create songs which speak to the theme of exile as it applies to people all over the world.

Emotional signposts

So while he sings the lyrics in his native Berber dialect, the music itself speaks to, and for, those who don't understand the language. A simple glance at the song titles is enough to tell us the focus of each track.

All we need do is follow the emotional signposts the music lays out for us and listen to the sound of Abdelli's voice to figure out the context and thought behind each one.

Take for example the third piece, "Ayahviv ruh" – 'Goodbye my friend'. It begins with the sound common to the music of North Africa, the plaintive drawling of a violin. Cracking with emotion, it is joined by hand drums tapping out a steady, quiet rhythm. Into this mix Abdelli drops his voice – not so much singing, as reciting the lyrics.

While we can't understand the specifics of what he's saying, we cannot help but feel the deep poignancy, the sense of loss, that lies beneath them. Because we don't understand the words, however, the song takes on an even deeper meaning than the personal tribute it may have started out as. We hear the mourning and take it to a universal level. We translate his pain felt upon the loss of his great friend into something that expresses the pain of any loss we may have felt, or that anybody could be feeling.

Those familiar with the music of North Africa will recognise the characteristic rhythm patterns of the small hand drums, the plaintive cry of the violin, the sound of the plucked mandola or the haunting vocalisations that send shivers up the spine in all of the songs on this album. However, Abdelli has moved beyond his personal comfort zone musically, incorporating musicians playing instruments you don't normally associate with the region.

In the ninth song on the album, "Oulim Verik" – 'Black hearth' – listeners are greeted by the haunting tones of a European concert flute. Beautiful and plaintive, it creates a mood that seems to suit the rather bleak title of the track. If a hearth is supposed to be a haven, the centre of one's home where cooking and heat are generated, then what is a black hearth?

If we extrapolate from the theme of the album, we can hazard a guess at its meaning. Abandoned homes, burnt out lives are all thoughts that spring to mind. Not understanding the lyrics put us at a disadvantage, but we can appreciate the emotional context of the piece. As other instruments join in to accompany the flute, the song picks up in intensity and begins to bring us back to the familiar North African territory.

In some ways this is typical of the album, and Abdelli's yearning for his native Algeria. While the recording contains music from other regions and features international musicians, it always comes back to the comfort of – and longing for – home, as represented by the instruments of his homeland and singing in his Berber dialect.

Sometimes when instruments and musical styles are merged in this manner the grafting sounds artificial and forced. Here, the music flowers and thrives, creating a sound which speaks to, and for, as many people as possible.

As current events continue to remind us, people all over the world are constantly being forced into exile. Driven from their homes by climate change, war, and poverty, the number of displaced people around the globe continues to grow.

Songs of Exile, created by an Algerian Berber exile and dedicated to a displaced European, captures the plight of these people and expresses some of their hopes and fears through music. It is a beautiful work that deserves to be listened to as much as possible.

© Qantara.de 2021