The not-so-universal art of writing

When I was five or six, I had a friend, a neighbour the same age, who would regularly come to our home. I wouldn′t call him a ″playmate,″ because we never played children′s games together.

Our friendship amounted to talking about far-off days, imagining what they would be like. Sometimes we would also talk about things that made us happy and things we hated. I remember him one day showing me the bruises where his mother had beaten him, saying, ″Today I asked my mother why she gave birth to me.″ He said this, of course, with his habitual smile, which only made it doubly bitter and indelible.

Why was I born?

From that time on and until years later, neither the obvious nor latent truth in the bitterness of what he said was clear to me. Perhaps it was at the end of high school, when for the first time I began to recollect and retrieve years gone by, that I saw everything afresh. It was during the period when I was writing my first short stories that I realised how painful the creature′s indictment of his creation, how pitiful his protest against it, the sentence ″Why did you bring me into the world?!″, was.

I saw how much creation itself had been challenged by the question, rearing up as it did to full height and demanding, ″Is life worth any price?″ My young friend had grasped circumstances in his childish world that made oblivion preferable to being.

As it happens, this preoccupied me for years, undermining my will to write and my creativity. I was forever thinking about the short stories I had lost in being without a home, writings that I was never able to publish, or that I censored or distorted – and about fictional characters that, because of my countless shortcomings, were born prematurely, remaining perpetually unfinished. I would ask: don′t they have the right to denounce their creation? Don′t they have the right to take me to court?

Doubtless those words, those images and those events were entitled to a better life, a life that I had denied them. How cruel! With the passage of time I came to believe that engaging in creativity, of whatever sort, must be done responsibly. I then took refuge in utopian notions, determined in my belief to write either the best possible work or not to write at all.

For several years, the effort crippled most aspects of my life, leading, in particular, to a withdrawal from writing, to phobias and obsessions. However, the compulsion to write gradually took hold of me and I realised the essence of life was something else, something incompatible with these utopian notions. I began again to write stories that were flawed, but this time with the more fundamental question before me: why, basically, do I write?

1 – Why I write

The why of writing is a fundamental question. Most writers spend their entire lives writing, having withdrawn from the world, but never asking themselves in a serious way: why?

Writers as a rule are, from the very first, acquainted with the art of seeing things for what they are and precisely examining the developments around them. They excavate. They cast their gaze on existence, nature, society, history, life and even within themselves in a mad search for fresh subjects; but they do not question their motives or their reasons for writing. Writing, for them, is so intuitive that to question the why of it seems ridiculous and pointless.

Whenever I see an interview with a writer, I expect the question to come up and am eager to hear the answer. To this day, the answers have been evasions, rarely getting to the heart of the question.

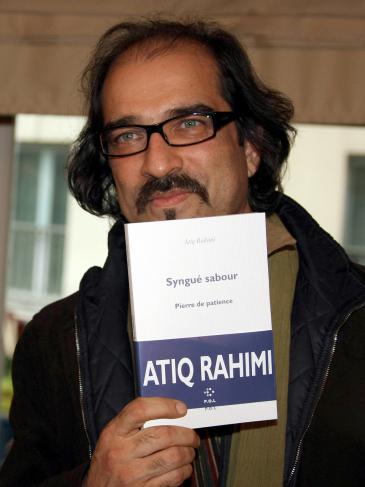

One of my favourite answers is one Atiq Rahimi, the author of ″The Patience Stone″, gave to a newspaper five years ago. He said, ″I write to know why I write.″ But in this statement the reason for writing is so obscure and elusive that, without a determined search and taxing persistence, it will never be known. Admittedly, one can reach a stage of self-awareness through the rigour of writing.

But the most recent reply I have seen to this fundamental question was in an interview in the local media with another Afghan writer. The reporter asked him, ″Why do you write?″ Perplexed and flustered, the writer quipped, ″Why do you smoke?″

Frustrated that he didn′t have an appropriate response, the writer felt that this unexpected and derisive question was meant to make fun of him, so he went on the offensive. The writing and smoking analogy and his responding to the question with a question were defensive reactions and conscious, of course.

I do not care much for the analogy, as I think that what triggers the onslaught of words on writers is something greater than what drives them to smoke cigarettes; but is the question, in fact, so frightening? If so, why? Writers and poets have placed their faith in writing and faith does not tolerate logic.

Challenging believers′ assumptions and beliefs has always been difficult and unpalatable for them. They know their fate is tied up in words and they must write. But they don′t know why. They say it is an inner penchant bound up with their very beings and souls.

It is due to such a motive that a number of writers ascribe their work to an uncommon talent and a number discover it in a spiritual power. In my view the question is manifold, with multiple responses and, like all fundamental questions, defies an absolute answer. It is a question for all seasons, one a person can grapple with for a lifetime and never tire of it.

2 – A journey of self-discovery

Leaving aside the question of why write and the attempt to find answers to it through a journey of introspection, we can raise other questions like ″How to write?″, which appear less difficult.

It so happens that the techniques writers use are more or less alike, there being no more than a few limited types. Initially, an event takes place and a dormant desire suddenly awakens in them, or in some that desire is awake from the start.

Whatever the case, the event that awakened my desire was reading a short story by the Russian writer Maxim Gorky called ″The Creepy-Crawlies″. A pitiful slice of life, the story takes place in a basement hovel where a beautiful boy, clever but disabled and his mother, a prostitute who is always drunk, live.

The scene is written so effectively and compellingly that it changed my life forever. I still see in my sleep that dank hovel and the inquisitive boy, so full of hope.

Influenced by that piece, I wrote my first short story called ″Thorn Bushes″, hoping one day to represent the life of a sensitive lad living with an appalling mother. The boy I had known in the distant past and whom I had, by chance, lost forever – the same one who taught me to object to life for the first time.

This was how the question of existence and its essential nature became a constant in my soul, remaining there to this day. Seeing the suffering of people and other creatures that possess a measure of life triggers in me a series of disturbances and surprises which never grow old.

Every day for years I have seen young boys and girls begging in the streets; I know of young people and the aged who have to do backbreaking work and I have also heard of women and children who are ill-used for innumerable purposes. Each of these becomes a pretext for me to go over everything afresh. These days the number of young children begging or working on the streets of Kabul is greater than at any other time I can remember. Their faces, the way they look at you, ask, ″Why did you summon us to existence? We were quite happy not existing.″

I say, ″What are you complaining about? That′s life. We all come into the world unbidden. Everyone suffers in one way or another.″ But at once I regret what I′ve said. I have misgivings. I am plunged into helplessness and doubt. Is that how life is? I don′t know. The question takes hold of my soul. A while ago I read that a small girl in Manila, the capital of the Philippines, caught Pope Francis, the leader of the world′s Catholics, off-guard with the same question.

Many parents there, owing to their financial difficulties, let their children run wild in the streets. The little girl, apparently one of those children, with the eyes of millions of eager worshippers on her, voiced the very word of protest with which my small friend had challenged his mother and which Gorky had perfectly depicted in his short story: ″Why?″

Then with eyes full of tears, the girl added, ″Children like us haven′t sinned, so why are we being punished so harshly?″ Pope Francis said, in all sincerity, ″I don′t know. No one knows.″ Perhaps a journey of introspection is also necessary to discover the truth of this.

To tell someone′s life, the writer has to get to grips with these tough questions and engage readers in the struggle. Knowledge of life requires a perpetual search. The writing of life, for me and for many writers, is that search: a means of engaging in a never-ending examination of ourselves and our surroundings, an endless looking into questions that have no answers.

3 – In Afghanistan

Writers the world over are members of one family, writing with common tools, with similar motives and methods and preoccupations arising from life. Literature is a table generously spread and laid out for everyone. This is the same for all writers, whether Afghan or German, Eastern or Western.

Writing begins. Inside the writer a great commotion erupts, but after that each writer follows his own particular path. These paths diverge from one another. Each writer gradually tends to favour a different style, different subjects in writing.

It is here that our towns, countries and circumstances in life directly influence our understanding and writing of the world – they demonstrate their importance. In creating stories and characters, each writer is, at the same time, telling a larger tale: the tale of the self.

The writings of Afghan writers are filled with self-censorship and demands for freedom, anxieties about finding security and the next meal, diverse complexes and privations. It′s probably for this reason that these writings seem shallow and ordinary to someone from another country.

A work that comes out of Afghanistan exists, like its author, in a struggle with the bare essentials of life and basic human needs. Thus we writers live on separate islands. Afghan writers during the period of the civil war and of the Taliban became reporters and elegists and in the modern period employees and food-seekers.

The most difficult challenges we face are the lack of readers and the absence of a market. Writers and artists cannot live off what they create and receive no backing from local institutions. Given this situation, it′s no wonder that writing and art are relegated to third, often fourth place in terms of importance. It is an entirely individual activity, confined and limited to the writer′s or the artist′s private corner. Obsolete to society, it cannot flourish.

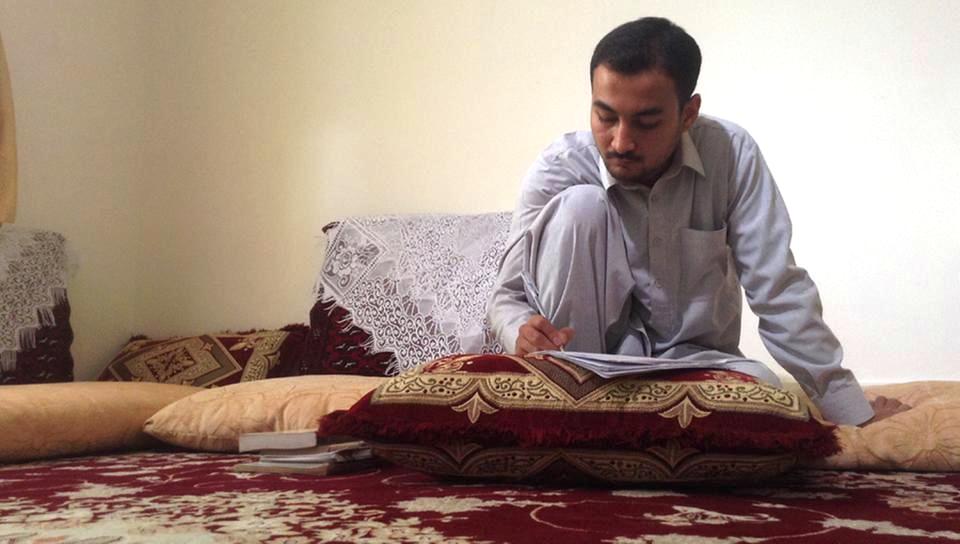

The phrase ″private world″ brings me back to my youth, when I found pleasure in playing with words. No more than a child, I wrote meaningless sentences. I probably also tried to write poetry. I struggled to put those sentences down on scrap paper, which I would lose after a few days. I constructed my private world, which admitted no one else, from bits of paper and pens. I became proud and delighted in having it. My world of words consoled me for those everyday defeats and failures of mine, which, naturally, were not few – failures stemming from war, exile and extreme poverty.

In discovering stories, I found direction in my life: they freed me from the never-ending confusions of my youth. I felt that I would never find success except in stories – leaving aside the question of what success is or can be. I began reading enduring works of world literature, favouring above all Dostoevsky, Chekhov, Flaubert, Marquez, Stefan Zweig and Nietzsche. Apart from being my favourite authors, they were teachers who taught me how to embrace the observation and narration of life as it is.

In this way, before I found meaning in writing, writing itself became meaning for me and an excuse to live. Do I exist to write? Or do I write to exist? I don′t know. Perhaps no writer knows. It was thus that becoming a writer became my calling. There are times when I ask myself: if I had lived in a more tranquil part of the world, would I have found myself as transfixed by writing?

But what about those who do live in tranquil places and devote their lives to writing? How did they discover the ″life of writing″? Would they need those private worlds as much as I and we do? Maybe yes, maybe no. Perhaps in some other way.

Taqi Akhlaqi

© Fikrun wa Fann 2015

Translated by Paul Sprachmann

Taqi Akhlaqi is an Afghan author and journalist living in Kabul. His first theatre play was staged in a theatre in Munich in June 2015.