Pakistan Is Critical to Any Settlement

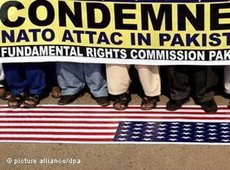

Pakistan's decision to boycott the Bonn conference is a great mistake. The staggering loss of life it suffered from the US bombings of its border outposts in which 25 soldiers, including two officers, were killed has shocked the nation, but there is a great deal of domestic politics at play here.

The civilian government has been at odds with the army over the resignation of Hussain Haqqani, Pakistan's ambassador in Washington, and his possible involvement in a memo that asked the US to take action against Pakistan's generals. The government has now gone overboard in siding with the army over the deaths of its soldiers.

Bonn 2 – a meeting of the international community attended by about 90 foreign ministers marking the tenth anniversary of the first Afghanistan Conference in Bonn – seeks to lay down the world's future course in Afghanistan until the West's withdrawal in 2014. Pakistan is an essential component in that process. It needs to be there and take part. It already faces severe diplomatic isolation in the region and among its allies despite its ongoing tensions with the US.

By silencing its own voice at such an important conference, it is blaming not just the US but the entire global community; it is creating further doubts about its intentions over its future role in Afghanistan – something that will deeply trouble the Afghan government; and it is signalling that it wants its own solution for Afghanistan rather than one that is in step with the world.

Bonn 2 will reassert the commitment of the international community to helping Afghanistan after 2014, by which time most Western military forces will have left the country. That commitment is becoming more necessary as many Afghans fear a breakdown in law and order after 2014.

At the same time, in order to break the mould of the plethora of sterile conferences held this year, there are some hopes of a breakthrough on reconciliation between the Afghan government and the Taliban.

But delegates at Bonn 2 must also pledge to grapple with the problems the Western alliance is leaving behind in Afghanistan and to help the Afghan government find solutions for them. About 90 foreign ministers, over 1,000 delegates, 34 members of Afghan civil society, and 3,000 journalists will be in Bonn to commemorate the first Bonn conference in 2001 that created the Afghan interim government led by Hamid Karzai.

Negotiations with the Taliban

It is still hoped that a real breakthrough on the ground will take place with the announcement in Bonn that the Taliban, the US, Qatar and Germany will agree to open an office for the Taliban in Doha, Qatar, so that talks between all sides can continue in a more permanent manner. However, much depends on how quickly the Americans, who are deeply divided on the issue of talks with the Taliban, agree among themselves.

Earlier hopes that the Taliban might send representatives to Bonn 2 appear to have been dashed by the lack of progress in the secret talks following the murder of peace advocate and leader of the High Peace Council, Burhanuddin Rabbani, on 20 September. Well-informed sources say that the secret talks between the US and the Taliban, which were brokered by Germany and Qatar and began earlier this year, have continued since Rabbani's death. Progress has, however, been slow.

The nations in attendance in Bonn will no doubt give a rhetorical endorsement to continued economic aid, training for the Afghan armed forces and help in governance after 2014, although many Afghan officials question whether economic aid will actually flow given the worsening recession in the US and Europe.

Three urgent problems facing Afghanistan

There are, however, several problems that the international community ignores at its peril. Firstly, there is the danger of economic collapse in Afghanistan after Western forces leave. Tens of thousands of young Afghans who work at Western military bases and embassies – the very generation that the West has nurtured over the past decade – will be rendered jobless.

Some 90 per cent of the US$17-billion Afghan budget is foreign funded, while US$5–6 billion is needed to maintain the newly trained Afghan army. Future funding for all this is promised by the West, but no concrete steps have been taken to guarantee the money and reassure the Afghans. The Afghan economy cannot sustain its population at present, let alone the infrastructure the West has built.

Secondly, the internal problems faced by Afghans are multiplying. These include increased ethnic tensions between Pashtuns and non-Pashtuns – which some Afghans feel are deteriorating rapidly – the reluctance of many non-Pashtuns to accept reconciliation with the Taliban, the continued uncertainty about the reconciliation process and the future of the Afghan constitution.

The next presidential elections are due to take place in 2014. Although Hamid Karzai cannot stand for another term and the field will be open to all-comers, there are growing demands that the constitution be reopened, examined and changed from a presidential form of government to a parliamentary system. There are demands that the highly centralized powers of the central government be devolved to the provinces and calls for decentralization and devolution.

Moreover, if peace talks with the Taliban bring about a ceasefire, and if substantial power-sharing negotiations between the government and the Taliban then take place, it is likely that the Taliban will also want to reopen the constitution and will demand amendments to it. All sections of Afghan society are demanding political changes within the next 24 months, but neither the Afghan government nor the international community is prepared for this. Any such changes must be carried out peacefully through debate and not through the force of arms.

Thirdly, there is the regional problem, the role of the neighbouring states and the continued interference of some of these states, including Pakistan, Iran and India. Last month's Istanbul conference was supposed to ease regional tensions, but in fact worsened them by highlighting how deep the divisions between the countries really are.

Pakistan holds the key

Pakistan, which hosts the bulk of the Taliban leadership, is critical to any settlement. Unless the Pakistan military cooperates with the Afghans and the international community, acts more flexibly than it is doing at present and unless the ever-worsening US-Pakistan relations improve, progress on reconciliation will be deadlocked, and improvements in Afghan-Pakistani relations will stagnate.

An enormous amount is at stake in Afghanistan, and a great deal needs to be done before Western forces leave. Bonn must take a long, hard look at all these problems and come up with some answers.

Ahmed Rashid

© Süddeutsche Zeitung 2011

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de