Islamic Modernity

An enormous whirlwind of change has been unleashed by the upheavals in the Arab world and the long-term effects remain unforeseeable. The most intense eruption took place with the start of protests in Cairo two years ago.

A number of social changes can already be observed. These societies, mostly made up of young people, are casting off their patriarchs. Since tasting the new freedom, they will never again yield to an authoritarian system. However, a great deal is in flux. After decades of ossification, change has gripped the Arab world. It is experiencing a turning point, even though it is one soaked in blood.

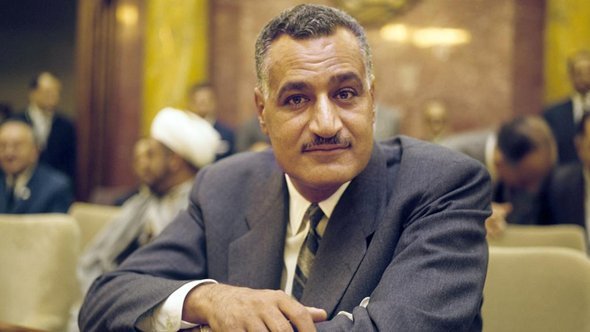

On the path to an authoritarian state

The course set by the Egyptian dictator and socialist Gamal Abdel Nasser (who ruled from 1952 to 1970) and continued by the Iraqi Saddam Hussein and Libya's Gaddafi, has come to an end with Syria's Bashar al-Assad.

A grave deformity of the modern age was the belief by the leaders of the Middle East that the state itself embodies modernity. They wanted to introduce change via powerful state control rather than through a vibrant society. Yet, this path did not lead to modernity, but instead to authoritarian regimes.

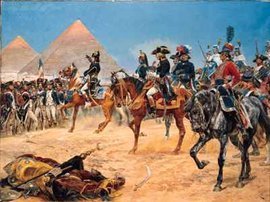

Since Napoleon's expedition to Egypt in 1798, Western methods and institutions have penetrated all areas of Arab life. The new ideas and concepts, however, merely formed a façade. The power structures behind it remained intact and unchanged.

The state in the Arab-Islamic world was more despotic as all of its predecessors, as the rulers were able to expand their powers with the aid of modern developments. The bureaucracy tightened its hold on citizens, modern technology enabled countrywide control, and a modernized security apparatus smothered any opposition.

Today, a variety of forces are operating in different regions of the Arab world. In the Eastern Mediterranean, the colonial borders drawn up in 1916 are now coming under question, as are the structures set in place in North Africa after 1798. If Syria falls apart, then the Sunnis in Iraq will ask themselves if they want to continue to live under Shiite domination. And the Kurds will not let the opportunity to have their own state for the first time simply slip away.

These are extremely sensitive, if not explosive processes, but perhaps they are unavoidable. The Middle East is more unevenly fragmented by ethnicity and religious affiliation than Europe ever was. In smaller states, the majority of citizens would share a common identity. Democratic structures could develop easier than in societies overcome by chasms of mistrust.

Less West, more Islam

In North Africa, with the exception of Libya, where a dangerous stateless vacuum has arisen, states will hold together on the basis of their historically developed national identity. Here, the pressure to establish new states is less powerful.

What is being called into question, however, are the "achievements" of 1798. Napoleon's expedition led to the secularization of the public sphere by Egypt's ruling elite, allowing individualism to take hold. Nonetheless, Arabs tend to associate the century of "Western modernity" with colonialism followed by military dictatorships.

It is therefore not surprising that the vast majority in the Arab world longs for a new beginning – less West and more Islam. This could be termed an "Islamic modernity." And it poses a dilemma for the new rulers. The Islamists mistrust the Western concept of all-encompassing freedom for the individual and lay far greater stress on the notion of the common good than in the West.

Islam wants to see freedoms limited, yet the revolutions took place in the name of freedom. The new rulers in Tunisia and Egypt have shown themselves unable to ideologically reconcile these contradictions. They are attempting to establish a new balance through pragmatic policies. The result will be hybrid solutions that will chart a middle course between autocratic government and a liberal social order, between the precepts of Islam and the demands of the revolution.

Sharia not seen as a nightmare

Muslims do not regard the Sharia as some kind of nightmare. In contrast to perceptions in the West, it is not understood as a narrow legal corset. Islamic jurisprudence is known as "fiqh". Sharia, on the other hand, means how to do something in the "Islamic way", namely, to know what is good and what is bad, what is meritorious and what is reprehensible.

Turkey only partially serves as a model for this transformation. Political Islam is always a product of its environment. Erdogan's AKP arose within the framework of a more or less functioning democracy where there were clearly drawn limits for Islam in the public realm.

These preconditions do not exist in North Africa. This doesn't mean that the Muslim Brotherhood, after years of being suppressed, can simply rule over its country. Perhaps they control the institutions, yet, opposition, even violent opposition, will continue to come from the "street". This is why in Egypt, President Morsi has called upon the military for help.

Rainer Hermann

© Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung/Qantara.de 2013

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de