The new wave

A generation ago, libraries and bookshops didn′t have a Young Adult section for Arabic books.

Many Arabic novelists who came of age in the 1980s and 1990s read popular, inexpensive genre novels such as the ″Future Files″ series by Nabil Farouq, which debuted in 1984, or the genre-spanning Egyptian Pocket Novels. Others read the romantic novels of Ihsan Abdel Qodous, or Agatha Christie′s translated detective stories.

Teen bibliophiles still pick up popular novels written for adults. In a recent report, the Egyptian Board on Books for Young People said local teens were gravitating toward Ahmed Mourad′s thrillers and Essam Youssef′s novel about drug addiction, ″1/4 Gram″. At the 2016 Sharjah Book Fair, publishers said young Emirati readers were drawn to new releases by social-media celebrities. But in the last decade, literary offerings for teens have been undergoing big changes.

A brief history of Arabic YA

The new wave of Arabic YA started around twelve years ago, perhaps with the 2005 release of ″Refuge″ (al-Malja′) by innovative Lebanese writer Samah Idriss. After that, slowly but surely, well-crafted books aimed at teens began to make their way into bookshops, libraries and schools.

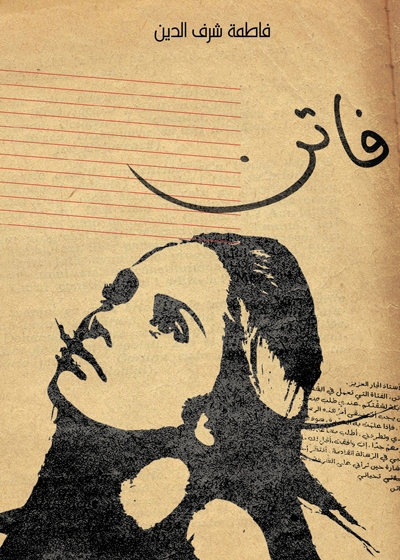

A second landmark was the October 2010 release of Fatima Sharafeddine′s lucid, moving ″Faten″, translated into English as ″The Servant″. This novel, which follows a teen whose father sends her to Beirut to work as a maid, reached both teen and adult audiences. It even won the Beirut International Book Fair′s Best Book award in December 2010.

Seven years later, Sharafeddine says, her novel is required reading in a number of Lebanese schools. Her latest YA novel, released in late 2016, also centres on an important social issue. ′Cappuccino′ foregrounds domestic violence, ″an issue that is a taboo in the Arab world as much as it is elsewhere.″

In 2013, the profile of Arabic YA rose again with the launch of a Young Adult Book of the Year category from the Etisalat Prize for Arabic Children′s Literature. The inaugural prize went to Noura al-Noman′s ″Ajwan″ (2012), the first book in al-Noman′s popular science-fiction trilogy.

Most new Arabic YA has been firmly in the social-realist tradition. But teens may be hungry for more science fiction and fantasy. Mona Elnamoury, who recently translated Ursula K. Le Guin′s acclaimed ″Wizard of Earthsea″ into Arabic, says the popularity of the Harry Potter novels has spurred an appetite for more Arabic science fiction and fantasy.

There have been a few SF titles after Al-Noman′s trilogy. But Al-Noman′s still stands out. In ″Ajwan″, a nineteen-year-old alien barely escapes the destruction of her world. Later, she must save her infant son from an organisation that wants to turn him into a super-soldier. Al-Noman recently said that ″most people I′ve talked to don′t consider it YA. They tell me it′s for 18+.″

Generally, Arabic YA novels are more socially conservative than their counterparts in English or French. Sharafeddine says Arab novelist shouldn′t rush to imitate novels written in other languages. ″The language and culture affects the content to a great extent. We need to start from the inside out, not the other way around.″

But…a little more romance?

Still, teens may be looking for a little more sizzle in their novels. Jordanian writer Taghreed Najjar has been shortlisted twice for the Etisalat Prize′s Young Adult category and her charming ″Sitt al-Kol″ is slated for release in Italian translation. In Najjar′s YA novels, there is a ″hint of romance,″ expressed in ″a look, a blush, a quickening heartbeat, a yearning – and no more,″ she said. ″No touching and of course no kisses.″

But, Najjar said, ″one eighth grader who recently read ′The Mystery of the Falcon′s Eye′ said she loved the book, but she wanted me to write about the romance in detail – lots of details.″

There′s also some confusion between books for tweens and books for teens. The 2016 Young Adult Book of the Year prize went to Rania Amin′s ″Screams Behind Doors″ (Sorakh Khalf al-Abwab). Yet Amin sees her novel as geared not toward teens, but younger ″middle school″ readers.

Amin agreed that books for teens should have a little more romantic frisson. ″Teens need to read about what they care about most, which is love and relationships,″ she said. ″And we, as writers, are not permitted to go near that area, or at least we cannot be as honest and realistic as we should or would like to be.″

Colloquial or standard?

Language is also an issue in books for young people. The characters in Amin′s charming ″Screams Behind Doors″, illustrated by popular graphic novelist Magdy al-Shafee, speak in Modern Standard Arabic. This formality seems a bit out-of-place in what is otherwise a fast-paced, conversational book.

Amin says she originally wrote the dialogue in Egyptian Arabic. But the publisher changed it to Modern Standard Arabic, ″because we have to consider competitions…plus consider the market in other Arab countries, which I believe is sad[.]″

Sharafeddine, on the other hand, commented that ″Standard Arabic is a very elastic and beautiful language and we authors have to appreciate that and make use of it in our works.″

The Etisalat Prize, awarded each November, has clearly directed a lot more attention and effort toward Arabic YA. But Amin, although grateful to have won, says writers shouldn't "write for publishers and competitions." By focusing on young readers, she says, "we are going to do a much better job and we will actually find we have an audience."

Marcia Lynx Qualey

© Qantara.de 2017