We were robbed of our health, our youth and our innocence

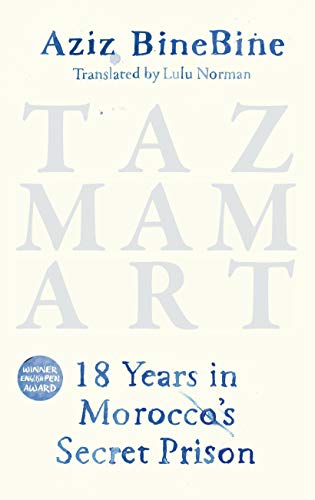

While Aziz Binebine’s memoir is neither the first nor the most eloquent of the testimonies ot come out of Morocco's notorious Tazmamart prison, it fills an important place in literature and in history. In the literary landscape, the book is important because Tahar Ben Jelloun’s multi-award-winning, bestselling novel Cette aveuglante absence de lumiere (That Blinding Absence of Light) was based in large part on an interview with Binebine, which Binebine disavowed in an open letter. This, then, is Binebine’s chance to tell his own story.

In part, it’s because the majority of Tazmamart testimonies come from the prisoners who were in Block 1, while Binebine was housed in the much more deadly Block 2.

The first coup

The story of Tazmamart begins two years before the first inmates’ imprisonment, on 9 July 1971. That’s when Aziz Binebine and others at the Ahermoumou training school received orders to prepare for live firing exercises the following day.

On 10 July, some officers apparently thought they were being driven to the drill grounds at Benslimane, while others knew they were headed toward the palace of King Hassan II, where – they were told – the king’s life was in danger. All agree on one thing: they didn’t know they were about to participate in an attempted coup.

Binebine’s narrative tells us little that’s new about the coup. The shooting had started before he and his cadets left their vehicles. Binebine writes of how he wandered around the palace, "desperate and disoriented." When he realises he has taken part in a failed coup, he runs to the palace parking lot, where he finds a Fiat 600 with the keys in the ignition. He first drives to an uncle’s house, then later turns himself in.

Here as elsewhere, Binebine’s account is markedly less lyrical than Tahar Ben Jelloun’s. In The Blinding Absence of Light, the protagonist thinks back to the attempted coup and sees it in vivid colours: "Who still remembers the white walls of the palace of Skhirate? Who remembers the blood on the tablecloths, the blood on the bright green lawn?"

Although Ben Jelloun’s novel is more poetic, it also has a false quality to it, particularly when read against Binebine’s personal narrative.

Binebine was convicted in a show trial and initially sent to Kenitra military penitentiary. But after a second well-known coup attempt in 1972, Binebine writes, rumours began to circulate about the construction of a secret prison.

Then, in August 1973, "hordes of police officers and gendarmes swarmed the building, opened our cells one by one, blindfolded and cuffed us and loaded us into trucks parked in the prison yard," Binebine writes. "Even during the coup itself, I’d never seen a deployment of force on this scale."

These fifty-eight men who participated in some way in the coup attempts were taken to an airbase, flown to an unknown location, and then taken on trucks to another unknown location. It would be years before their friends and family would have any sense of where they were.

A wall of silence

Aziz Binebine’s father – who was a close companion to Hassan II – famously disavowed his son soon after the coup. But starting in the fall of 1973, many prisoners’ families worked tirelessly to find them: particularly mothers, wives, and daughters. As word trickled out about the prison and its location, activists made public allegations, but Moroccan authorities consistently denied them.

It wasn’t until 1990, and the publication of Gilles Perrault’s Notre Ami le Roi (1990) that a significant crack appeared in the wall of silence around Tazmamart. This was followed by renewed public pressure from activists and other governments. Finally, in September 1991, Aziz Binebine and the other twenty-seven survivors were taken out of their cells, and stood "just as we had on the first day, but without our health, our youth, and our innocence."

These prisoners were taken briefly before the media; their photos were taken, and their stories were told by others. But for the rest of Hassan II’s life (1929-1999), the prisoners themselves remained largely silent. Former Tazmamart detainee Ahmed Marzouki was assisted by journalist Ignace Dalle in composing Tazmamart Cellule 10 (Tazmamart Cell 10) a few years after Marzouki’s release. One chapter appeared in print in 1993. But, according to scholar Johanna Sellman, the two decided to delay publication until "a change occurred in the political climate."

In July 1999, Hassan II died, marking an end to the country’s repressive "Years of Lead". In 1999-2000, former Tazmamart prisoner Mohamed Raiss published an account of his experiences, which were serialized in a newspaper in Arabic. After that, a flood of narratives appeared, including Tahar Ben Jelloun’s novel. It was published in 2001, apparently based on a talk with Binebine that the former prisoner did not know would be turned into a fictional narrative.

Son to the King's jester

Binebine’s narrative mostly recounts the stories of other prisoners inside Tazmamart’s terrifying Block 2 and doesn’t tell us much about his personal psychology.

Although Binebine comes from a famous family, we hear little about his father, who is often referred to as the king’s jester. Aziz Binebine’s brother, the artist and writer Mahi Binebine, has written a fictionalised portrait of their father Le fou du roi (The King’s Fool). But while Aziz says little about their father, it is clear he was wounded.

One of the most terrifying aspects of Binebine’s account are the psychological cruelties the prisoners inflict on one another.

Near the end of the memoir, Binebine and another prisoner, Captain Bendourou, have a bitter argument. In it, Binebine tells the other man he’s a cuckold, and the other man flings his father’s betrayal in his face. The argument – which also appears in Ben Jelloun’s novel – is vicious, and shortly after Bendourou gives up and dies. Binebine says he repented and did what he could for the man, "washed his pots and clothes while he cursed me and accused me of stealing his things." But Bendourou died in May 1991, shortly before they were freed.

Ultimately, Binebine’s Tazmamart narrative is less artful than the others, most of which were co-composed with professional writers. Yet that is also what makes Binebine’s the most achingly real.

Marcia Lynx Qualey

© Qantara.de 2020