Hope for a Proper Revolution

The revolution proper is coming. It must and it will. Egypt has had enough of autocratic patriarchies. The foundations are shaking. The intense public rejection of autocracy in all its forms with its unbearable repressions that started two years ago is not letting up. With every attempt to contain the revolution its forces get stronger. This is the physics of revolution.

The revolution unleashed on January 25, 2011 constituted the most massive politicization in Egypt's modern history. While its immediate aim was to expel the corrupt autocrat the overall purpose was to demolish the machinery of despotic authoritarianism in all its entrenched political, economic, and social strangleholds and to rebuild the country into a functioning democracy worthy of the name.

A vibrant tableau of revolution

Patriarchal tyrannies, such as Egypt has experienced – and is now under the thrall of in its latest permutation – must be extirpated in all their guises.

Hegemony of the ruler over the ruled, of some classes over others, of some groups (religious or civil, ethnic or racial) over other groups, of elders over youth, of men over women form part of the grid of tightly calibrated power and control that is patriarchy. Recognizing and naming this nefarious package is part of undoing it.

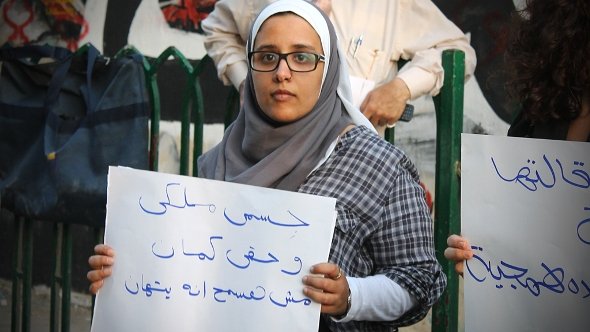

When the country rose up two years ago Tahrir Square became a vibrant tableau of revolution: women and men, young and old, Muslims and Christians, badly-off and well-off bearing signs, banners, flags, headbands, and painted faces emblazoned with the words and symbols of revolt.

During the now legendary eighteen days Egyptians experienced unprecedented – and unfettered – national unity when collective attention was focused on expelling the patriarchal dictator. When the mission was accomplished oligarchs in the wings came forth with military insignia flashing to depoliticize the national revolution by trying to instigate through suasion and force a return to "normal."

In the name of physical and economic security the military patriarchs, the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces wanted people to go back to their former lives as if the revolution was over. To entrench itself as the new political patriarchal power it was necessary for the SCAF to dispel the revolution by dispersing the revolutionaries unified by their passionate commitment and vision of a transformed Egypt built on the dismantled subjugation along all axes of oppression.

The revolution's dependency on women

An early sign of new autocratic creep came when the SCAF pushed the formation of committee to draft constitutional amendments which was notorious for its conservative composition and absence of women.

Belonging to all segments of society, women were the first to directly confront the new hegemonic rulers.

On March 9th on the occasion of International Women's Day, when women went out on a march from Tahrir in a stunning display of commitment to the principles of the revolution they were assaulted verbally, bodily, and sexually by thugs seemingly "under contract" along with other misogynist roughs freely joining in. When soldiers moved to pick up women protestors and subject them to virginity tests it unmasked the complicity of the military and announced their recognition of the centrality of women to the success of the revolution.

As a potent revolutionary force, women had to be removed from public political work. In the script of the new controlling uniformed patriarchs women must know their place and return to it. They must be agents in putting the pieces of the old life before the revolution back together. Yet physical and sexual scare tactics as methods of containing women and stifling the revolution proper have not worked. Young women together with young men have been effectively confronting assaulters of women in public spaces and are not giving up.

Islamism and patriarchal control

With the ascendancy of Islamists to political power another kind of patriarchal control came to the forefront with its own methods of hobbling women and the revolution. Their trump card became legal and religious control and indeed, the blurring of the two. The new constitution, voted in by only sixty per cent of the limited numbers going to the polls in the recent referendum, allows for increased power of the presidency and enhanced role of religion. It tightens the mandate that all laws must be based on the sharia, i.e. Islamic law.

The constitution - by failing to guarantee women's equal rights - sets up the possibility for a slide backwards. The constitution locates "the woman" in the context of the "authentic Egyptian family" calling for the balancing of her responsibilities in the family with her roles in society. Men are cast as heads of family while their needs to balance such an onerous responsibility with their public roles are not mentioned.

The patriarchal model of the family supports the structure of the patriarchal state. We might also ask what is "the authentic Egyptian family"? Is it one of the multitudes of female-headed households? Is it rural families in which spouses share work to keep them viable? Is it the wealthy urban family where women are "supported and protected" by prosperous spouses? Is it the two-career middle class family?

The revolution, grounded in the insistence of the equality of all citizens, is at loggerheads with the regimes of the patriarchal state and family. The Islamist-headed patriarchal state is against the revolution and the revolutionaries who pursue an egalitarian order as integral to the triumph of social and economic justice.

The revolution is postponed

Meanwhile there are secularists calling themselves liberals who appear to harbor patriarchal attitudes when they show themselves reluctant to publically insist on the full and equal rights of women, most evident in putting women at the bottom of electoral lists. All of this puts the breaks on the realization of a proper revolution.

The acceptance of subjugation of human beings based on one kind of social category endorses subjugation based on any kind of social classification. The young revolutionaries and women, both at the bottom of the patriarchal structure experience its inequities most. The young women and men who put their lives in the forefront of revolution know that half a revolution is no revolution at all. These revolutionaries are not about to let religion be (mis)used to thwart the project of societal transformation.

The young revolutionaries know well that as long as patriarchy prevails in any of its guises and uniforms, the revolution is postponed. Time is on their side. Two years out, herein lies the hope for a proper revolution.

Margot Badran

© Qantara.de 2013

This article was previously published on Ahram Online.

Margot Badran is a historian and a specialist in women’s studies who focuses on the Middle East and Islamic world from the late 19th century to the 21st century. She is a senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington. Her most recent book is "Feminism in Islam: Secular and Religious Convergence".

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de