The rotten Empire

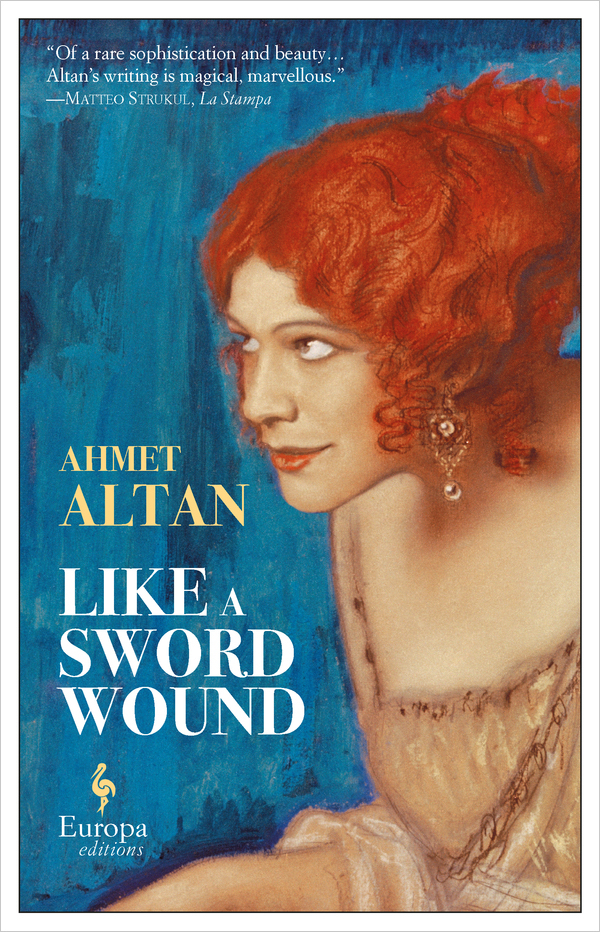

The first book in Altanʹs "Ottoman Series", "Like A Sword Wound", which traces the beginning of the end of the Ottoman Empire and the end of the ruling Sultans at the dawn of the 20th century, is a significant work of fiction in its own right. Given the current situation in Turkey, it becomes even more pertinent. In its depiction of an autocratic and corrupt leadership desperately clinging to power, the book sets up ready comparisons with the way the current government is attempting to exert control over the Turkish population.

Readers can expect more than just a straightforward historical political novel. Altan draws us in deep to demonstrate just how much history depends on those who are doing the telling. We encounter this chapter of history both through the eyes of those who lived it, and through the eyes of the main protagonist, Osman, who lives at some unspecified time in the future and believes he is being visited by the ghosts of those alive during the time in question.

Osman travels back and forth between the past and the present. The ghosts of his long dead family invade his filthy and impoverished room to regale him with their tales full of spite and personal bigotry. One has a personal hatred for the women in the story, claiming they are all whores who lead men astray while others merely want to recount what happened. Another is a soldier in the Sultan's armies, while others are dignitaries attached to the palace, including the Sultan's personal doctor and his son.

A chorus of ghosts

All these ghosts are commentary, or if you like, a chorus, offering reflection on the tale which unfolds in the past. However, everything occurs in the present – we watch events in both time periods as if they were taking place as we sit and watch. In fact, Altan has created a past far more real than the so-called present.

Osman appears to live in a hallucinogenic world occupied by the ghosts of the past who fill his ears with their versions of events. However, while he is hearing these distorted histories, Altan provides the readers with detailed accounts of the actual events.

We become the observers to what really happened. We see all the intrigues, machinations and plots that are hidden from nearly everybody else, watching how the players' lives actually unfold, which differs remarkably from the way in which Osman's visitors describe them.

Altan deftly weaves a number of different storylines together to present a detailed picture of a crumbling empire. From Eastern Europe to Istanbul, through the eyes of soldiers and civil servants, we see both how the desire for self-rule in Bulgaria and frustration with the Sultan himself at home in Istanbul all contribute to the slow dissolution of the Empire.

The Sultan himself is depicted as a weak man who allows the pashas running the various government ministries to use their positions of power to carry out petty vendettas and line their own pockets. In fact the government is not only morally, but financially bankrupt as well. Indeed it is so poor it can no longer pay its soldiers.

The first rumblings of discontent among the military towards the Sultan and his pashas are sparked by little more than self-interest. While some of them see the merits of allowing places like Bulgaria self-rule, others still consider the idea treason. One thing they agree on is that the Sultan needs to do something about the corruption in his government.

Disdain, ennui, dissolution

Unsurprisingly the picture Altan paints of the Turkish upper classes as a whole isn't very flattering. They are all we've come to expect of aristocracy in the waning days of empire. Workers and poor people demanding their rights, or simply food, don't know their place and should be dealt with accordingly – out of sight and without disturbing the peace and quiet of their betters naturally.

But their decadence is even more profound than mere disdain for the rest of society. Boredom and lack of sensory stimulation leads some of the aristocracy into sexual experimentation. Two characters in particular, Hikmet Bey and his wife Mephere Hanim, transition from conventional sexual acts between a man and a woman to threesomes with their children's French nanny.

Although this may not strike some as totally unusual, it seems they simply drift in that direction due to boredom, mirroring the dissolution of an ordered society. Considering the time and place in which these actions are described – an Islamic country where women who fail to cover their heads in public are viewed as immoral, they become even more disturbing.

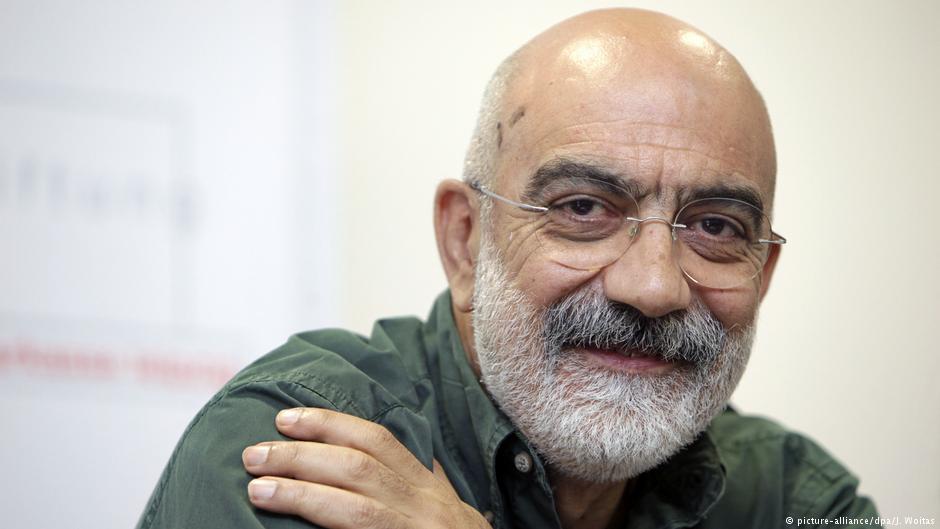

While parallels between the events in this book and present day Turkey are easily drawn, especially as Altan is currently in jail for ʹsubliminallyʹ encouraging the coup against President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, it was written in 1997, long before the current regime came to power. Yet, even without this direct connection, Altan's history of defending Kurdish and Armenian minorities in Turkey makes his critique of past Turkish nationalism all the more relevant.

In some ways "Like a Sword Wound" reads like a grand adventure story: intrigue, suspense, romance and politics on an impressive scale. However, as each little incident is described in detail, from the in-fighting in the palace to the conditions aboard Ottoman naval vessels, we realise there is a deep current of rot running through the entire undertaking.

Richard Marcus

© Qantara.de 2018