We woke to find them gone

What would happen if all Palestinians living inside Israel suddenly and inexplicably vanished, at the stroke of midnight, as if taken by aliens or shape-shifted by Cinderella’s fairy godmother? What would happen to the stories they left behind?

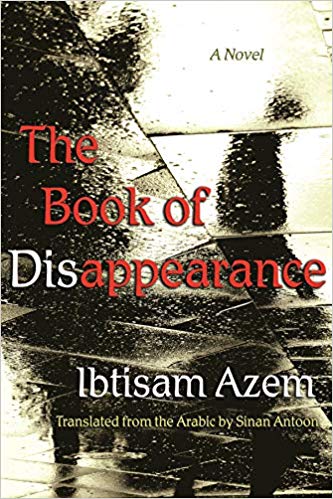

This is the question that animates Ibtisam Azem’s The Book of Disappearance, which was published in English this summer, as translated by award-winning novelist Sinan Antoon. Mass disappearance is a theme that often permeates Palestinian narratives, but Azem’s novel brings a new, speculative-fiction twist – after this mass disappearance, nobody who’s left seems to know how or why it happened.

The book opens with a much smaller and more prosaic disappearance: that of a main character’s grandmother. Alaa soon finds his missing grandmother, who passed away while sitting on a wooden bench, looking out at the Jaffa shore.

Most of the book takes place in Jaffa, a city many Palestinians fled during the violence of 1948. But Alaa’s sharp-tongued grandmother steadfastly refused to go. "I never liked Beirut. I don’t know why people like it so much. Nothing worth seeing." Alaa’s grandfather left for Beirut without his wife, apparently intending to return when things calmed down. But he never did come back.

What happened in Jaffa was also a mass disappearance, the novel reminds us. In 1948, Jaffa’s Palestinian population dropped from around 100,000 to a tiny group of around 4,000.

Yet these disappearances can be explained. As Alaa’s grandmother once told him, "The bullets were everywhere. They used to shoot at us whenever we went outside our houses."

Mysteries do remain – such as why Alaa’s grandfather would have left his pregnant wife behind – and these echo the book’s bigger unknown: why have the Palestinians disappeared once again?

The 21st century disappearance

After the loss of Alaa’s grandmother, we shift to Ariel, the main Israeli character. He’s a journalist and a liberal centrist, happy to be tolerant of Arabs as long as it doesn’t require much by way of personal sacrifice.

He’s also a neighbour of Alaa’s, and they had gone out drinking together the night before the disappearance. When Ariel wakes up, he finds Alaa and all other Palestinians gone.

In subsequent chapters, we see Palestinians failing to show up to work picking flowers, doing surgeries, and driving Israeli buses. Newspapers aren’t delivered; cafes aren’t opened.

We see guards at Prison 48 panicking when they call out the numbers of those whom they believed were behind bars. When the army enters Palestinian homes, they find TVs still on, tables full of food.

In the novel, most Israeli citizens’ first reaction is to believe the Arabs must be on strike. The first news bulletin, at eight in the morning, declares a "state of maximum emergency…because the Arabs have declared a general strike. ... All of the Arab inhabitants of Israel, Judea and Samaria, and Gaza have disappeared."

According to this initial report, "It is worth noting that neither the Arab leaders in Israel, nor the Palestinian Authority, had declared their intention to stage a strike." The broadcast ends with a cheery, nothing-is-amiss weather forecast: "Sunny with temperatures reaching 20 degrees Celsius."

Not everyone believes it’s a strike. Ariel listens to a call-in show where a man named Daniel thanks "our brave soldiers who carried out a clean operation to rid us of the fifth column and terrorists who were around us everywhere." Is that what’s taken place? While the on-air expert urges caution when potentially blaming the Israeli Defence Forces, he certainly doesn’t rule it out.

The consumption of Alaa’s life

When tens of thousands fled Jaffa in the spring of 1948, their homes were often assigned to incoming settlers. In The Book of Disappearance, Ariel has a neighbourly spare key to Alaa’s apartment. At first, he bangs on the door. But when there’s no answer, he tells himself that Alaa will understand if he enters. At first, perhaps it’s just to check on his neighbour. But this quickly shifts to a nosy curiosity as Ariel tries out passwords on Alaa’s laptop and picks up the red notebook that served as Alaa’s journal.

Ariel doesn’t take pleasure in this snooping, as it’s too similar to "that feeling he used to dislike back when he was doing his military service." Nonetheless, he reads his neighbour’s notebook. Here, he sees not only Alaa’s life, but memories of Alaa’s grandmother. Yet instead of building sympathy between them, Ariel feels a new sense of ownership over Alaa’s story.[embed:render:embedded:node:14419]It doesn’t take Ariel long to get used to this new world without Palestinians. He and others do feel flashes of regret and fear. A bartender at the nearby Chez George tells Ariel, "Maybe the Arabs will crawl out of every corner like zombies and return to exact revenge." But twenty-four hours after the disappearance, no zombies show up. In fact, "They didn’t find a single drop of blood. They were relieved that the army either wasn’t responsible for the disappearance, or it had executed it perfectly."

Ariel packs an overnight bag so he can stay in Alaa’s apartment. This comes as the prime minister declares that whoever is not in the country by 3 a.m. the next morning will lose their place in it. Even before that deadline passes, Ariel’s mother calls him, eager to obtain one of the old Arab homes on Haifa’s Abbas Street.

Ariel, meanwhile, is focussed on Alaa’s notebook, which he wants to turn into Chronicle of a Pre-Disappearance. He plans to select and translate excerpts into Hebrew, interspersing his own commentary. Ariel doesn’t need Alaa’s apartment, but he plans to get the locks changed soon after the deadline passes.

The plot outline might seem a bit on-the-nose – Palestinians disappear, and Israelis usurp their lives – but the book’s beauty is in its execution. Azem creates suspense through the creation of sympathetic and flawed characters. After all, how could a decent person take over his neighbour’s house? In The Book of Disappearance, we see how it happens, step by step.

Marcia Lynx Qualey

© Qantara.de 2019