Fading under fire

On 31 October 2010, a group of transnational militants forced their way into the Church of Our Lady of Deliverance in Baghdad, where regular Sunday worshippers were gathered. The militants fired on church-goers before they took hostages, holding them until Iraqi commandos stormed the building and saved around half of those within. Nearly sixty were killed.

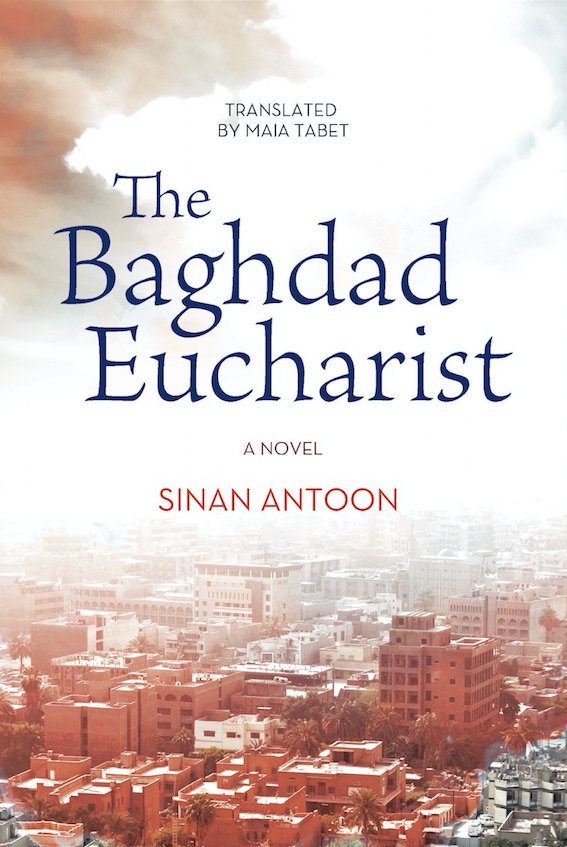

Sinan Antoon′s ″The Baghdad Eucharist″, shortlisted for the 2013 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, is anchored around an echo of this massacre. Yet instead of happening in 2010, the fictional attack is moved into the future by several years, to a different 31 October.

Nearly all the book′s action takes place on this single tragic Sunday. It′s told through two voices: elderly, optimistic Youssef and his deeply depressed young niece, Maha. The former is a retiree who doesn′t want to leave Iraq, while the latter is a student at the University of Baghdad′s medical school, hurriedly finishing her education so she can flee.

The two voices are sharply different. Youssef′s tone meanders through Iraqi history, fondly touching on family photos and memories. Maha′s is relentlessly, miserably present. Both look back at their country′s history, but with an entirely different gaze. They see approximately the same events, but come to radically different conclusions about Iraq′s past, present and future.

One history, two observers

Both Youssef and Maha are bright, critical observers. Youssef is hopeful and positive without whitewashing the crimes of the present or past.

He does recall fond stories about family and friends, but he also remembers how a close friend′s father had his assets frozen and property confiscated, such that they had no choice but to emigrate. Youssef remembers the moment his Jewish friend told him, ″My father has registered our names under the emigration law. We′re going to Israel.″

When Maha looks back and thinks about the exodus of Baghdad′s Jews – which she is far too young to have seen first-hand – she piles this on top of all the other frightful brutalities. It also serves as an echo of what might yet happen to Baghdad′s Christians.

Youssef never married, but he looks back with pain and fondness on his great love, Dalal. The two were unable to marry not only because of their age, class and educational differences, but also because he was a Christian and she a Muslim.

Still, Youssef can′t help but see Iraq as a largely welcoming place, where he was able to booze with his buddies, rise in his career and generally enjoy his life. It′s the recent past that Youssef sees as different.

In the scope of his whole life, Youssef sees the contemporary rise in sectarianism as a squall that will pass. He is surprised by the rhetoric on TV, but remains distant, ironic: ″I swear to God, even the date palms are Sunni and Shia now.″

Maha cannot manage this sort of detachment, even in her arguments with Youssef. She experiences the rhetoric of contemporary Iraq as present, immediate, infuriating and inescapable.

While this leads Maha to become more deeply religious, Youssef remains a casual believer, none too exercised about the particulars. "To me, Christ was an immortal sacred tree that withstood storms and floods and came back to life every spring."

Youssef sees Iraq as his country, but Maha can′t imagine any place for herself. When she looks at old photos in a Facebook group called ″Beautiful Iraq″, she reflects on what members call the ″good old days″ and doesn′t find a happy time among them. Rather, she thinks of how Assyrians were killed ″even during those halcyon days of royal rule″ and how Iraqi Jews had ″effectively been expelled from their country overnight after being collectively dispossessed″ and hadn′t, she asks herself, ″poverty been widespread?″

The question of Iraq′s Christians

Antoon has said, in an interview with al-Akhbar, that this novel′s central question was ″to leave or not to leave Iraq.″ By the end of the book, it′s difficult to see this as a viable question. At one point in the narrative, a group Muslims do try to make room for Christians to return. Their efforts come soon after Maha is married and she was ″moved when I saw some of them looking straight at the camera and urging their ′Christian brethren,′ as they called us, to return to their homes because the area was now safe.″

Maha and her husband take them up on this offer. They return to her family neighbourhood, where she gets pregnant while continuing her studies. Things are going well until a bomb goes off near their home and Maha miscarries.

Antoon′s description of Maha′s miscarriage is heartbreaking. Here, the world changes not just because of the lives lost, but because of those who aren′t allowed to come into being.

Indeed, one of the book′s central questions seems to be: how will Iraq change without Youssef, Maha and the baby who never lived? How does the nature of a country shift with the loss of each person, each community? How does collective memory change?

Poetry, memory and loss

The book′s two sections are tonally quite different, yet each has its own poetry. Youssef′s section is interlaced with modern and ancient Iraqi poems, from Abu Nuwas′s eighth-century drinking verse to twentieth-century al-Jawahiri. The poems come both from Youssef and from his drinking buddy Saadoun. Maha′s poetry, on the other hand, is church liturgy and Fairouz songs, much of it depressing. The narrative is further embroidered by a beautifully rendered Syriac Catholic Christianity. Translator Maia Tabet brings all of this warmly and sensitively into English.

″The Baghdad Eucharist″ is a story of a community at the precipice, captured by Antoon in a fragile and threatened moment. Both Youssef′s and Maha′s ways of viewing Iraq – as a welcoming and diverse nation and as a frightening and dangerous place – are given equal weight. And yet it′s hard to do anything but see things Maha′s way and fear for the community′s future.

Marcia Lynx Qualey

© Qantara.de 2017