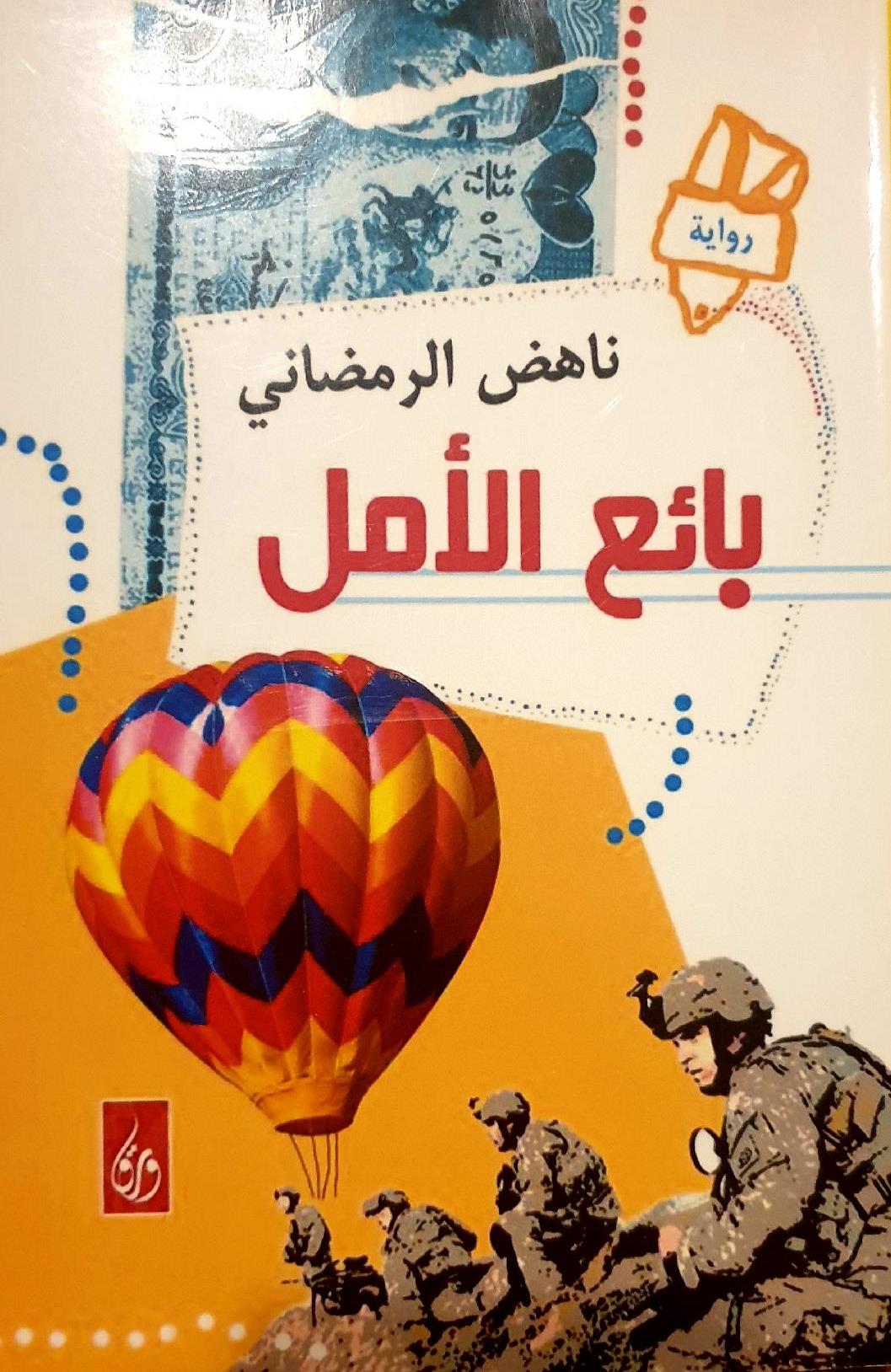

A successive shattering of dreams

In a race against time, ever hopeful of avoiding the impending war, Nahidh al-Ramadhani began his diaries prior to the ultimatum issued to Iraq in 1991 regarding the withdrawal of its troops from Kuwait. An army lieutenant at the time, he questioned his own urge to write while awaiting possible death. Pinning his hopes on achieving his dream, however, Ramadhani brushes all pragmatism aside. "I want to talk! To scream", he says, capturing a sense of the salvation some seek through writing.

Such utterances echo throughout this wondrously odd mixture of literature, autobiography and chronicle, in which Ramadhani is both the narrator and the protagonist. He wrote to his unknown audience uncertain whether his words would ever be read, documenting the situation in his hometown of Mosul, a city he describes as "the world's biggest cemetery".

The book describes life in the shadows of death's hovering ghosts, fear under dictatorship and the violence of ʹregime changeʹ in 2003. At times, it is hard to differentiate between the author's experience and the events happening around him. Despite the fact that Ramadhani writes of recent calamities, rather than trawling through past history, "The Hope Vendor" put me in mind of Orhan Pamuk's "Istanbul: Memories and the City".

The aspirations of the optimistic protagonist are subject to a continuous tragedy of blows. His hopes of a peaceful withdrawal from Kuwait are dashed with the outbreak of war in 1991. He talks of Iraq's shocking defeat, the heart-breaking destruction of Kuwait's infrastructure and the dictator's orders to kill any dissident soldiers in cold blood, abandoning them with no food or supplies in the desert. Starvation is narrowly avoided when the soldiers stumble upon a lone camel, a bloody feast Ramadhani refuses to partake of.

Harsh sanctions and ghosts of censorship

Under such dire conditions, defeat was inevitable. The author records moments of surrender, oscillating between the will to live and thoughts of suicide in a bid to avoid humiliation. Finally, he wound up a war prisoner in Saudi Arabia, where he spent four months. For Saddam Hussein, however, the debacle was still a "victory".

From his descriptions of Iraq in 1990s, little appears to have changed. Arguably, the situation has worsened. "Bereaved elderly women, broken men, heavy bullets fired into the sky, crowded trains, flag-wrapped coffins, black airplanes bombarding cities, missiles falling on poor neighbourhoods, sparse flesh, widows in their twenties, amputated limbs, and eyes with no light." This is how Iraq looked three decades ago and how it still looked in 2015.

It is an account that describes a life under constant air attack, fluctuating exchange rates, days of misery and the failure of any project a man might seize upon to support his family.

Ramadhani highlights Saddam's contradictory behaviour – arresting Islamists in 1994 while calling on his Baathist comrades to learn verses from the Koran by heart. At times, the book takes a political turn, mentioning the attempt to assassinate Saddam's son and the escape of his sons-in-law to Jordan in 1995.

"Why do we have holidays? What is the point in a country ruled by a dictator?" Ramadhani expresses his frustration, describing a police state in which people are afraid that even walls may have ears.

He writes of short stories penned only to be hidden in drawers to avoid censorship or worse. Keen to see democratic change in Iraq, Ramadhani perceives a struggle between "a generation that knows how to change but does not dare, and a generation that wishes to change, does not know how – and yet is ready to sacrifice."

In 1997, the author left Iraq to seek a better life teaching in Gaddafi's Libya in uncertain circumstances. We learn of his – at times – precarious existence and the difficulties of crossing Egypt when travelling from Jordan to Libya by bus. Five years later, in 2002, and Ramadhani is in the United Arab Emirates, scooping up literary awards.

Jumping to 2014, he resumes writing in the days prior to the terrifying rise of IS, which went on to engulf large swathes of north-western Iraq, to say nothing of Syria. Here, Ramadhani uses two concurrent timelines, recalling his time spent in Libya and his fear of minefields in Kurdistan in late 1980s, while chronicling the political upheaval in Iraq. Like many other Mosulis, Ramadhani blames the government for delivering the city to a terrorist group, in a politically calculated move aimed at securing Nouri al-Maliki a third term.

"Two invasions a decade apart"

In 2003, Ramadhani documents his wrath on seeing the invading U.S. army wandering the streets and decides to resist the occupation. He begins working for an anti-occupation newspaper, supported by Atheel al-Nujaifi, who would subsequently go on to become Nineveh's governor. Faced with ongoing advertising enquiries from the U.S. army and pressure from Islamist groups to promote terrorist propaganda, the novelist soon left the newspaper. Instead, he established a private school dedicated to resistance through education, furnishing his students with knowledge and "happy memories" – something Iraq's new generations desperately need. We have to blame politicians rather than soldiers, he says, because "soldiers are forced to fight".

Observing the forced exodus of Christians from Mosul, the author laments the loss of centuries of peaceful co-existence and the disruption of the city's unique identity. Fleeing the ghosts of IS, Ramadhani prefers to dwell on happy memories, such as when his play "Amado" is staged in Luxembourg in German.

Predicting the mass destruction that re-taking Mosul from IS would entail, Ramadhani concludes his thirty-year chronicle on a hopeful note, reminding us that Iraq has survived wars and long years of death and destruction, and will rise from the ashes again.

Gilgamesh Nabeel

© Qantara.de 2019