Preserving the 'rich heritage' of Byzantine music

"This music aims to touch people's souls," said Thomas Anastasiou, 35, a Greek Cypriot chanter from a nearby district. "Singing with people around us is something very important for us."

The UN's cultural agency UNESCO inscribed Byzantine chant on its list of intangible cultural heritage of humanity in late 2019 following its nomination by Greece and Cyprus. UNESCO describes the tradition as a "living art that has existed for more than 2,000 years", and an integral part of Greek Orthodox Christian worship and spiritual life, "interwoven with the most important events in a person's life", from weddings to funerals and religious festivals.

Shortly after, the coronavirus pandemic outbreak halted or put limitations on everything from concerts to church attendance. But now as restrictions continue to ease in Cyprus and elsewhere, celebrations this Orthodox Easter on the eastern Mediterranean island are moving closer to normal.

One Sunday evening in the lead-up to Holy Week, dozens of people gathered for vespers in the Panagia Church in the heart of Ayia Napa, a seaside resort better known as a rowdy party town in the summertime. Boys and men, including members of the Cypriot Melodists Byzantine choir, carried the verses, sometimes to the drone of a bass note, as elderly women prayed, mothers rocked babies and visitors lit candles at the church entry.

"You fall in love with this music," said choir director Evaggelos Georgiou, 42. The music teacher recalled chanting alone in the church of his home village of Athienou at Easter two years ago, in the early days of the pandemic. "We missed this a lot," he said. "Now we are back."

'Treasure'

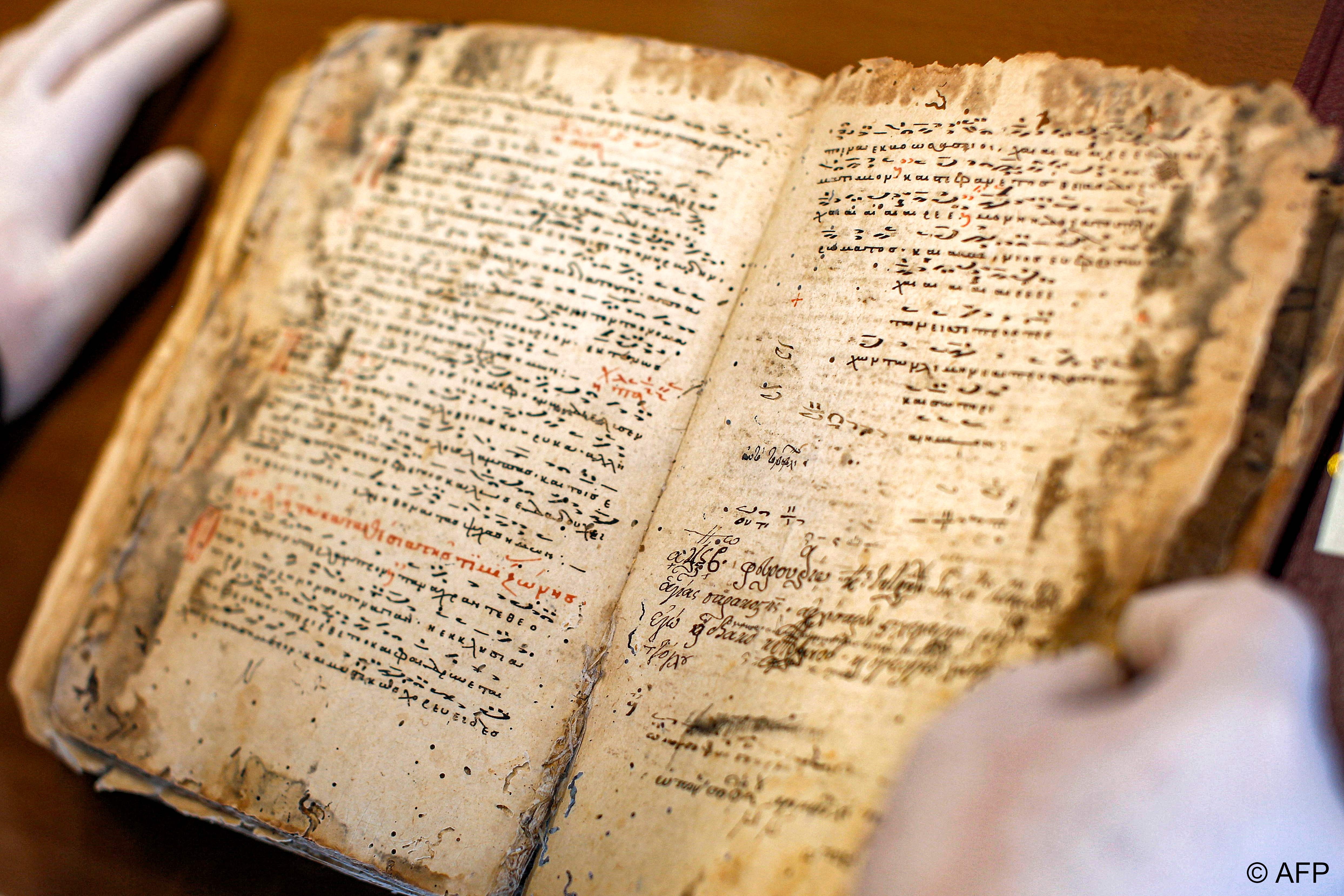

In the archive of the archbishopric in the Cypriot capital Nicosia, Father Dimitrios Dimosthenous examines a thick, 14th-century Byzantine chant manuscript, its fragile pages of mostly black writing pockmarked and stained by age, insects and humidity. Picking up his phone, he scrolls through an electronic version of the score's modern transcription, and the room falls silent as he begins to sing.

"This is the old way of writing the Byzantine music," he says, pointing at the carefully crafted lines. A new system introduced in 1814 expressed the notation in far greater detail.

Byzantine chant is monophonic and unaccompanied, and based on a system of eight modes. "It's very difficult to know the notation made before 1814 because it was like one sign was a whole melodic line," explained Christodoulos Vassiliades, a teacher at the Kykkos Monastery Byzantine Music School, noting the importance of the aural tradition.

The manuscript and others in the archive testify to the centuries-old practice of chanting on the island. Its original owner was the neighbouring former cathedral of St John, where Father Dimitrios served for 24 years and was the director of its choir. The old manuscripts are "a treasure for Byzantine music", he said, noting hymns to Cypriot saints. "I'm looking at my history."

'Perpetual student'

In the church of St John, Ioannis Eliades gestures towards one of the 18th-century paintings covering the walls and roof – a scene from the Old Testament of people chanting. It is "the only depiction (of chanters) that we have all over Cyprus", said Eliades, director of the Byzantine Museum in Nicosia and a member of Cyprus's UNESCO committee. The designation means Byzantine music "is appreciated not only in Cyprus but worldwide", he said enthusiastically. "It's a rich heritage... and it's important to safeguard it," he said.

While chanting is a predominantly male tradition, women sing in monasteries and sometimes in churches. Among them is graphic design student Polymnia Panayi, who has been studying at the Kykkos music school in Nicosia since 2018. Chanting "makes me happy and... helps me to pray", said the 22-year-old, who sometimes sings with other women at a local church.

The school has 60-70 students a year, aged around 10 to 60. Some 40 percent are female, said a representative of the school, noting "increasing interest" among women. Panayi expressed hope that more churches would open up to female voices.

"There are women that chant but they just don't have a chance yet," she said.

Back in Ayia Napa at the end of the vespers, chanter Anastasiou said "learning Byzantine music never ends". "You are a perpetual student, even if you are a teacher, as the sources of Byzantine music are... unlimited," he reflected.

"It's a neverending tradition." (AFP)