Where they speak Jesus' language

The ball flits through the air. It looks as though it might even sail over the church wall. The six young players beneath the bell tower with the metal cross give each other a few soccer tips. As their language echoes over the yard it sounds different to Turkish, it’s throaty like Arabic and sounds archaic, with a linguistic melody all its own. It’s a dialect of Aramaic, the language that Jesus is thought to have conversed in.

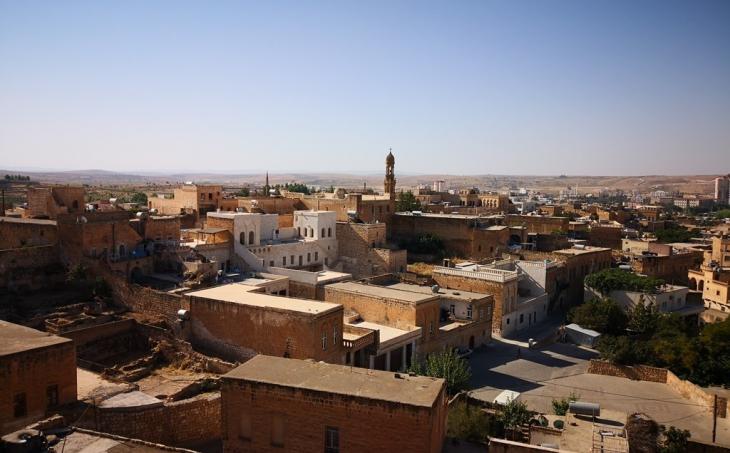

The evening sun has drenched the church yard in a mystical golden-yellow light. The caretaker bolts the heavy wooden door of the Kirklar Church, one of seven Syriac-Orthodox churches in the southern Turkish city of Mardin. Seven year-old Theodora is bored watching the soccer game. The first-grader has tied her soot-black hair into a ponytail; her mischievous grin reveals gaps in her teeth.

After a while, Theodora’s uncle Iliyo appears, the 22 year-old son of the parish priest. He puts his arm around his niece. "Theodora, speak German with the guest," he says in Aramaic. Theodora was born in Germany and lives with her parents and two siblings near Heilbronn. Now, in the summer holidays, she’s paying her first visit to the homeland of her ancestors, walking on the ground that Aramean Christians regard as sacred, in the heartland of the Syriac-Orthodox church.

Keeping the Aramaic culture alive

Here, her grandparents were wont to work and pray. "It’s a bit hot, but the children are nice here," Theodora lets her guard down. She doesn’t understand any Turkish, but she can talk to her peers from the Kirklar parish in Aramaic.

"My big sister, Theodora’s mother, left Turkey years ago. But we’re trying to keep the Aramaic culture here alive. We don’t want people to emigrate to Europe," explains Iliyo. "But of course we can’t prevent them doing it." Now, during the summer months, the Kirklar Church is offering courses in Aramaic, to help the descendants of early Christians improve their knowledge of the ancient liturgical language – both spoken and written.

Mesopotamia, the territory between the Euphrates and the Tigris in the tri-border zone between Turkey, Syria and Iraq has been the homeland of the Aramaic Christians for 700 years. The region, which includes the modern Turkish province of Mardin, is one of the oldest regions in the world to have been continuously populated by Christians. As representatives of a tradition that’s been unbroken since the beginnings of Christianity until the present day, churchgoers in the parish of Kirklar are living with a sense of responsibility.Economic hardship drove tens of thousands of Syriac-Orthodox Christians to settle in Europe in the 1960s and 70s. A second wave fled in the 80s and 90s during the Kurdish-Turkish war. Caught in the crossfire between Kurdish rebels and the Turkish army, the Arameans may not have been directly involved in the war, but they were nevertheless regarded with mistrust by both parties in the conflict.

Displacement, the abduction of village priests and a series of attempted murders on Christians drove entire villages into exodus. Today, the Aramaic population of Turkey is around 15,000. In Mardin, they say there are just under 100 families. In comparison: some 100,000 Syriac-Orthodox Christians live in both Germany and Sweden.

The worst times are over

"Fortunately, the worst times are over. During my youth in Mardin, I didn’t experience any more discrimination. Maybe a bit of teasing in school, but no big deal," says Iliyo. His father suddenly appears in the courtyard. He’s wearing a black priest’s cap and smiles at the group. The boys interrupt their game of football to respectfully kiss the clergyman’s hand. Theodora from Heilbronn gives her grandfather a hug.

To the east of Mardin, a road leads through the town of Midyat – which has a population of 100,000 – and deep into the region of Tur Abdin. The landscape here is a mix of bare hills and craggy chalk mountains quarried for the materials to build the houses of Mardin. In a region about the size of Belgium, agriculture has sustained people for centuries. As well as pomegranates, figs, melons and apricots, seven different types of grape are grown here, which the Arameans make into their famous wine.

There used to be 80 thriving monasteries in Tur Abdin (Aramaic for "mountain of the servants of God") – only seven are still in use. To this day, there are just as many church spires as minarets in the villages of this region.Enhil, a 15-minute drive south of Midyat at the end of a winding dirt track, could be symbolic of many places in Tur Abdin. The old Aramaic village with a view over the Mesopotamian plateau is a cluster of partially dilapidated houses on a hilltop. Today, 60 of the families in the village are Muslim and three Christian. Two churches serve as a reminder of the community’s former faith. Both of them are locked up. There’s a note stuck to the door of one of them with the caretaker’s telephone number on it.

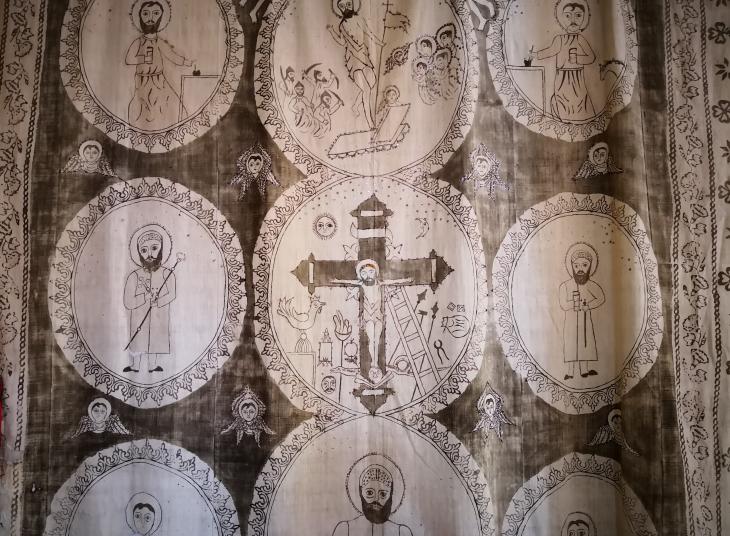

Ilyas arrives a few minutes later. The shy man with the angular face is wearing ripped jeans; his white T-shirt tucked into the waistband. Ilyas unlocks the church that was renovated in 2005 with donations from the German and Swedish diaspora. The refurbishment cost 700,000 Euros. The chancel is simple, in the middle lies a thick leather-bound Bible covered in swirling characters.

Training of priests prohibited

"We share the priest with other churches in the area. On good days, 30 people will attend the service, most of them from nearby villages," says Ilyas. But only in summer, when the diaspora Christians are visiting Tur Abdin. The fact that there are so few priests is also due to the law: to this day, the training of priests is prohibited. Those wanting to enter the priesthood have to move to Damascus, the seat of the Syriac-Orthodox Patriarch.

Christians in villages like Enhil are also dogged by conflicts over property rights. Over the past few years, as a result of structural reform in the province of Mardin, many of the monasteries and churches became the property of the state, ostensibly because of missing land register entries. In May, this decision was reversed and the places of worship returned to the Christian community. In some places there are land disputes with Kurdish neighbours who have set up home in the abandoned houses of refugee Christians.But just 10 kilometres to the east of Enhil, the picture is totally different: suddenly, two dozen smart stone villas appear from nowhere in the middle of the rocky desert. Over the past few years, returnees from Germany, Sweden and Switzerland have settled in Kafro, a village that stood empty for 12 years.

Built in the architectural styles used by their ancestors, the neat houses seem to send a message: we’re back to stay. On the edge of the village there’s a chapel with a stone plaque stating that it was sponsored by the church of Wurttemberg. In the village itself, there’s a flourishing pizzeria run by a returnee from Stuttgart. "Kafro’s Pizzeria" is very popular with young Muslims from the province of Mardin.

Tuscan scenes in Anatolia

Eating pizza in the vine-clad summer garden, a visitor might imagine that this could just as well be Tuscany as south-eastern Anatolia. Only ayran, the chilled yoghurt drink, locates the scene firmly in Turkish culture. This new prosperity in Kafro clouds a very recent memory: just 40 kilometres to the south over the Syrian border, the fate of Aramaic Christians looks very different.

During an Islamic State campaign in the winter of 2015, hundreds of Christians were abducted and murdered in the villages around the Khabur River, a tributary of the Euphrates. Most of the villages inhabited by Syriac-Orthodox Christians in northern Syria have been destroyed, churches burned and abandoned. IS violence has driven many Christians out of Syria into Tur Abdin. Within the Kirklar Church congregation too, many of the 150 Aramean new arrivals found refuge in Mardin. For them, the town is a base on the journey to Europe where as Christians, they believe they will have a better chance of being granted asylum.

Iliyo’s father co-ordinates the emergency assistance, arranging meals and accommodation for those refugees who don’t want to live in Turkish government camps. An irony of history: some of them are living in the empty houses of Christians who were themselves forced to leave Mardin during the conflict with the Kurds. In addition, many Arameans in Syria are descendants of Christians who had to flee Anatolia 100 years ago because of Ottoman persecution.

Iliyo thinks it’s highly unlikely that the true owners of the dilapidated stone houses in Mardin will ever come back: "If Aramaic Christians from Europe move back to Tur Abdin today, then they do it for spiritual reasons. Certainly not for economic ones. They do better in Europe," he says, adding that most of those returning from Europe are elderly people yearning for retirement in their homeland.

Nevertheless, there’s no talk of dying out in the Kirklar congregation of Mardin. In fact, there are also positive signs: for example, the Artuklu University in Mardin has been offering a course in Aramaic language and history for several years now, something that would have been inconceivable in Turkey 10 years ago. Amid what are otherwise gloomy scenarios concerning the future of the Middle Eastern Christians, the resilience of the Tur Abdin Arameans offers a glimmer of hope.

Marian Brehmer

© Qantara.de 2019