Together in the Search for God

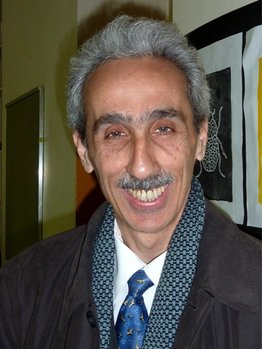

Talat Kamran looks content as he comes to the end of the conversation: for 90 minutes he's been talking to Richard Nennstiel, a Dominican monk from Hamburg, about Christian and Muslim mysticism. Some 70 people have been listening to what they had to say. "As I understand it," says Kamran, who's a Muslim from Mannheim, "a Christian and a Muslim can both have a similar experience as a result of mysticism, if they are sincerely looking for it. It's about the divinity which is in each and every one of us."

Christian-Muslim dialogue is a firm part of the programme of the Catholic Assembly, the Katholikentag, and it's now part of the routine of the gathering. This year, Christians and Muslims presented some 40 events, including mosque open days and offerings which continue throughout the weekend.

In the Johannes Kepler School on the edge of the city centre, for example, there's a "Space for Silence and Prayer", a "Mannheim teahouse", and a "Moroccan royal tent" in the school yard where people can meet. The police pop in to the teahouse for something to drink as they check that everything is alright.

Muslims at home in Mannheim

Kamran has lived in Mannheim for over 30 years. The city is his home. He's a Sunni Muslim born in Istanbul and he's head of the Mannheim Institute for Integration and Inter-Religious Dialogue.

The fact that Catholics are interested in Islam and want to talk to him fills him with enthusiasm: "I find it good to be able to deal with all aspects of religion during the Katholikentag. But that's just right for our city."

The centre of Mannheim is surrounded by industrial plants, and Muslims are a long-standing part of the city and its street scenes. Up to 50,000 Muslims live here, many of them in an area known as Little Istanbul, which is where the Johannes Kepler School is to be found. A few hundred metres away, and just across a small street from the Church of the Beloved Virgin, is the Yavuz Sultan Selim Mosque.

The building of the mosque in the 90s led to debates across the country. It is still one of the largest Muslim religious buildings in Germany. It was the debates back then which led Talat Kamran to get involved in dialogue, both on day-to-day issues and on matters of theological principle.

"Back then, we already had all the issues which are only being discussed now in the rest of Germany," he remembers. "And we dealt with them well, and managed to explain what Islam actually is."

A tradition of Christian-Muslim exchange

Christian-Muslim dialogue began formally at the Katholikentag in 1992, which took place in Karlsruhe. The Central Committee of German Catholics, the main organisation of lay members of the church and the organisers of the event, worked with the archdiocese of Freiburg, which was that year's host, to set the dialogue up on the lines of the Christian-Jewish dialogue which had already existed for some years.

The first event was attended by prominent guests, including the then-president of the Papal Council for Inter-Religious Dialogue, Cardinal Francis Arinze, and the Papal Nuntius in Germany, as well as leading members of the Central Committee. Arinze described the situation of Muslims in Germany as exemplary, and encouraged both sides to join the dialogue, although he also mentioned the often difficult situation of Christian minorities in Muslim countries.

At the time, there was no mosque in Karlsruhe which could act as a partner for the Catholics; they had to go to nearby Pforzheim.

Now, the dialogue has become so normal that the organisers didn't even notice that it was the twentieth anniversary of that first event.

It may not have been spectacular this year in Mannheim, but it was more extensive than ever before. The range went from elementary Islam to spirituality, and included topics like the ban on taking interest, the role of women, and mercy as a key name of God.

But another area of concern is the "Fear of the Other," anti-Christian and anti-Muslim feeling, the problems of Christians in Muslim lands. One highlight was the participation of bishops from Egypt and Iraq and priests from Palestine and India.

Speaking with Muslims, rather than about them

On the catholic side, the man in charge of programme and organisation is Father Hans Vöcking, a member of the White Fathers who worked for many years in the Arab world and is now in Brussels. "The dialogue at the Katholikentag has grown," he says. The experience of earlier years had shown him that it was difficult to get local Muslim partners, and that interested Christians often ended up talking to each other.

Now Vöcking praises the good preparatory work done in Mannheim, to which both the catholic and the Lutheran churches had contributed, with their contacts to the Muslim community. He says it's important that the Muslims are involved; it's not enough just to talk about Islam, one needs to talk to Muslims.

Radicalism and violence in Islam

That's what's going on in room 109 of the Johannes Kepler School. The last person in the question-and-answer session confronts Talat Kamran with a warning not to mix religions up, and she accuses Islam of being aggressive.

Kamran responds by referring to the current debate over the position of Salafist extremists in Germany, and speaks of "an incorrect interpretation of Islam". The mystics in his religion, he says, offer a different position, contrary to such violent or extremist groups. Hearing what he has to say, you can easily see his roots in Turkish Sufism.

The problem of radicalism and violence among Muslims comes up in the main programme too: just to take a couple of examples, the head of the Christian Democrat group in the German parliament, Volker Kauder, speaking in a session on the persecution of Christians, talks about the situation in Egypt and warns of an "Arab winter" following the "Arab Spring".

And Gesine Schwan, once Social Democratic candidate for the German presidency, warns of a "clash of cultures" arising from the current German debate about the Salafists.

Curiosity and ignorance

Not five minutes from the school is the mosque: German and Turkish flags fly out front and there's a big banner with the motto of the Katholikentag, "Dare to try a new beginning." To the left is the "women's entrance", to the right the "main entrance" and there's a Turkish bakery in between. On the first floor, Melahat Kurtaran is just finishing a tour through the building. Some 20 guests, mostly women, are listening, and like most of the Katholikentag participants, they have their special rucksacks on their backs.

For the time being, they're in their socks. They ask about the separation of men and women in the mosque, about fasting, alcohol, dietary rules and the pilgrimage to Mecca – as well as how Muslims north of the polar circle work out the exact time for the start of Ramadan.

Melahat Kurtaran has already taken several groups around today, but she answers all the questions patiently, and occasionally quietens down the children in the group. Kurtaran, who wears a headscarf and whose German has a strong Mannheim accent, explains the Arabic writing in among the intricate ornaments on the walls of the mosque. She tells of her own trip to Mecca with her husband six years ago.

The main prayer hall of the mosque has room for 1,000 people. Currently, a few young Katholikentag visitors are sitting quietly and almost contemplatively on the heavy carpet; there's one man praying near the front.

Closing the knowledge gap

"Of course there are things which divide us," says 60-year-old Volker Walter from Ludwigsburg as he puts his shoes back on at the end of the tour. "But we need to have tolerance and respect for other people's religion."

He and his wife are visiting a mosque in Germany for the first time ever today, although he had been to one during a trip to Egypt. He was particularly interested in the calligraphy, the way the space was decorated with Arabic writing, and the firm belief in one God as a principle of Muslim faith.

"It's important that we keep up the dialogue with Muslims," he says, "because we live with them, and we have many things in common in the Christian and Muslim traditions."

Christoph Strack

© Deutsche Welle / Qantara.de 2012

Translated from the German by Michael Lawton

Qantara.de editor: Lewis Gropp