Cairo's guardians of morality

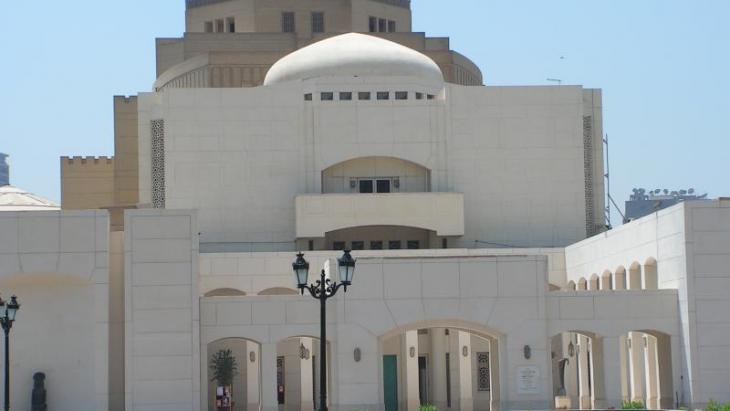

A couple of swift moves and Shady finds himself lying on the floor. "You have to roll properly or it won't look natural. And it will hurt." A trainer gives Shady and his actor colleague some last-minute tips before their performance the following day. The play "500s" is premiering at the Hakawy Festival at the Cairo Opera House. It deals with the subject of growing up in Egypt, first girlfriends and problems at school and with friends. The two young actors have to have a fist fight on stage.

Sondos Shabayek, the director of the play, stands in the corner of the darkened theatre hall and is nervously fiddling with her mobile phone. We had arranged to meet for an interview. "Sorry, but I can't right now," she says. "We have a massive problem." The next day, the massive problem becomes apparent from a posting on the festival's Facebook page. "Due to technical problems, the play '500s' has been cancelled."

"The term 'technical problems' is an extremely diplomatic euphemism. It was censorship, plain and simple," says Shabayek, adding that the theatre management has been upset by a particular scene in the play. "In the scene, we refer to the 'secret habit,' a slang expression for masturbation."

These two words were enough to have the whole play banned from the stages of Egypt's state theatres. "The management demanded that we rewrite the script and take out the scene." Shabayek refused. She had abided by all the rules, sending a copy of the script in advance to the state censorship board, which then authorised "500s" without changes, giving it a rating of "13-plus."

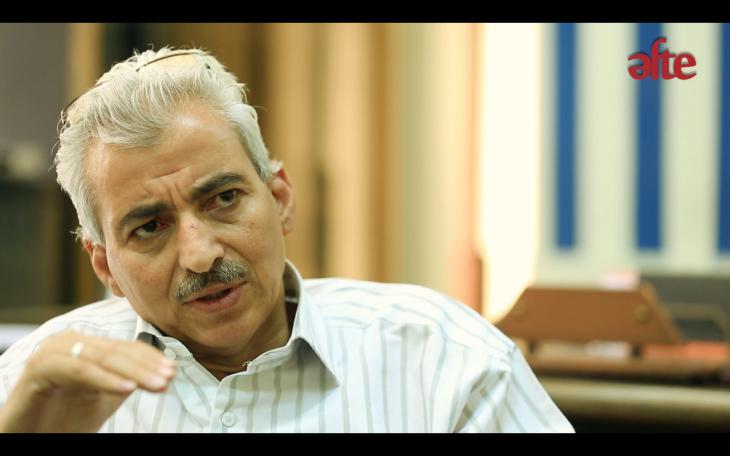

"We have three great taboos in Egypt: religion, sex and politics," explains Hossam Fazealaa. Nestled in between removal boxes, the delicate young man sits on an office chair that is still wrapped in plastic. In the corner of the fashionable office is a sign with the words "AFTE – Association for Free Thought and Expression."

Playing for the masses

For years now, Fazealaa has been investigating the background to and effects of censorship in Egypt. He has already published numerous essays on the subject. Nevertheless, Fazealaa still finds it difficult to say why the authorities are so obsessed with censorship. "I think that they are attempting to create some sort of model citizen in order to implement their ideology. It is easier if everyone thinks the same. That's the only way I can explain it."

In practice, this means that artists and creative individuals are subject to huge constraints. Before a project can even get underway, plans must be submitted to the Directorate for the Supervision of Artistic Work – an office under the authority of the Ministry of Culture. It is headed by Fathy Abdel Satar, a greying man of around 50 with a very clear idea of what constitutes good art and what doesn't.

"Every artist that has a clear conscience about his work has no problems with the censorship authorities," said Abdel Satar, speaking in the film "Authorised to be shown," which AFTE released just a few weeks ago. Abdel Satar is convinced that his office is doing creative artists in Egypt a favour. "There are many people who are grateful for our efforts, because we have helped them to knock their work into shape. We sometimes have to step in, as our staff possesses trained eyes and ears." He goes on to say that the Egyptian public doesn't accept just anything. Artists seeking success on the Egyptian market have to take the taste of the masses into account – and this taste is determined by Abdel Satar and his staff.

Political minefield

Indeed it is true that most complaints about films, songs or plays come from outraged citizens. Sometimes, they feel that too much naked skin was on show, thereby undermining public morality. Other times, they feel that their religion was being attacked. The biggest minefield, however, is politics. "Artists have stopped making controversial works, because it is simply too dangerous." Since President Abdul Fattah al-Sisi assumed power, the criteria for publically releasing a work have become even stricter, according to Fazealaa and his colleagues.

Under Mubarak, there was at least a small amount of latitude for critical films, plays or books. After the revolution of 2011, this margin for expression suddenly expanded enormously. All at once, there were lively public debates on politics, social problems and various models for society. "This window was shut tight two years ago with the removal from office of the Islamist President Mohamed Morsi." Anyone who dared to criticise those in power ended up either behind bars, banned from the media or forced into exile. Notable examples of this new trend are the blogger Alaa Abdel Fattah and the satirist Bassem Youssef.

No real artists left

What remains can be categorised as mainstream. "We don't have any real artists left in our country," states Fazealaa emphatically. "All of the films released in recent years look the same." Those who are truly talented either work underground or outside of Egypt, he says.

This is not an option for Sondos Shabayek. "Of course, I could complain and say how difficult it is to work in Egypt. But that is only half the truth." When she manages to get one of her plays on stage, it is mainly the audience response that keeps her going. "The audience is often so grateful that we address problems they have experienced themselves, but that are never talked about. And this alone makes up for the struggle we encounter in staging our work."

The five actors in "500s" sit on the small stage and whisper to each other. Shady is asked whether he has ever engaged in the "secret habit". The audience laughs out loud. Everyone knows what they are talking about, without anyone ever mentioning the word "masturbation". The play "500s" has finally managed to be performed on an Egyptian stage, albeit for a private audience.

Elisabeth Lehmann

© Qantara.de 2015

Translated from the German by John Bergeron