The Natural Pessimist

Even Ali Abdel Mohsen's T-shirt is a statement. Designed himself, it is white with an Egyptian eagle in the centre of a black and red circle. The eagle, a symbol of strength and unity, has become a sort of bull's-eye for Mohsen – a target of protest and contradiction, of anger and frustration.

The artist, born in 1984, works as a journalist with the English-language "Egypt Independent" newspaper, which belongs to the independent Shourouk Publishing House. The combination of art and journalism works well for Mohsen.

Last year, Abdel Mohsen presented his second solo exhibition entitled "Razor-Sharp Teeth" at the Mashrabia Gallery, located not far from Tahrir Square. The Mashrabia Gallery is well-known for promoting young, not yet commercially established artists.

Nature is wounded

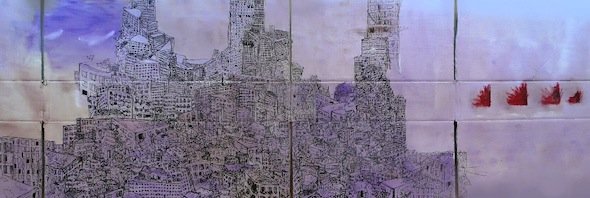

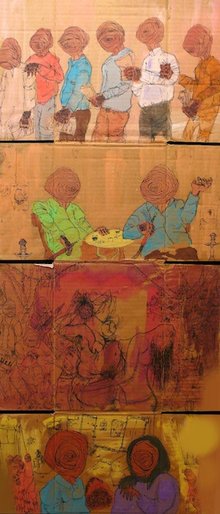

His water coloured ink drawings on torn cardboard have created a new kind of visual imagery that has nothing in common with oriental motifs.

They are disturbing, apocalyptical images of a world gone awry. Sombre scenes resplendent in red and black depict the ominous future of large cities. They portray the city as a wasteland made up of the skeletons of houses, as if after a nuclear attack.

Nature appears only in a wounded form, with trees reduced to mere strokes and bleeding animals pierced by spears. His people resemble uniformed, faceless beings with heads bound up like ancient Egyptian mummies. In one of his untitled drawings, gigantic hands loom over the scene, just as the former state apparatus interfered in the lives of Egyptians.

Joy, frustration and rage

None of the works in his still surveyable corpus directly deal with the revolutionary upheavals of two years ago. Nevertheless, definite references to Egyptian society and its struggle to find a viable path to the future can be seen in many of the images. As a reporter, says Abdel Mohsen, he can intellectually process current events, yet in art, he is able to express his feelings. These range from joy to frustration and rage.

Rage over the many victims that it took to topple the dictator. And scepticism about what is in store in the future for Egyptians. The drawings can also be seen as offering general observation on the challenges facing mankind in the 21st century.

"I am naturally a pessimist," says Ali Abdel Mohsen. The feeling of elation after the overthrow of Mubarak was real for the artist, but it has since dissipated. He questions whether there is truly a development towards democracy. This would require fundamental changes in Egyptian society. "Mental processes simply persist longer and we don't possess either the resources or the will to overcome this," he claims.

A revolution of Egypt's art world

In the art world, however, it has become clear that the revolution was also a revolt by the young against the domination of older artists. After the revolution, a number of young artists achieved fame in a relatively short time, whereas it used to be that senior members of the influential Cairo Atelier artists' association would determine the success of a career.

The individual plays no role in the images of Ali Abdel Mohsen. The men and women portrayed are all part of a faceless mass. In fact, the issue of individuality and the refusal of any sort of conformity is a central theme in his work and it runs like a thread through his whole biography. Even during his time at school, he suffered under Egypt's narrow social constraints.

He did not attend art school, but drew from early childhood and also made short films. He went to an American school and found it to be an artificial world, completely isolated from everything that was going on in Egypt.

He then studied Mass Communications at the Misr International University in Cairo. Ali Abdel Mohsen characterizes his time there as "brain washing". For a time, he was even expelled from the university, because he dared to challenge a lecturer.

A university lecturer had, for example, claimed that the Beatles all died from a heroin overdose. This was supposedly an example of Western decadence. Mohsen contradicted him and as a result was banned from attending lectures for a time. "Absurd," he says, shaking his head. "Our educational system is truly in a state of catastrophe." By his own account, his degree is hanging above the toilet in his home.

After completing his studies, he was fully disillusioned. He took part-time jobs as a waiter and cameraman, tried to sell real estate, and occasionally wrote a few articles. Then, in what was to him completely unexpected and without any particular effort on his part, important doors suddenly began to open. In contrast to his sombre artwork, his career path seems to be permeated by a great sense of ease.

He came into contact with the Egypt Independent and found pleasure in pursuing journalism. Since October last year, he has had a contract with the English-language newspaper and, at the same time, enjoys flexible work hours, which allow him sufficient time for his artistic endeavours.

By a similar stroke of luck, he was discovered as an artist. At an exhibition in the house of the ambassador of the European Union, he met Stefania Angarano, the owner of the Mashrabia Gallery. An exhibition in Mashrabia was followed in 2012 by a group show entitled "Identities" together with the more well-known artists Hany Rashid and Shayma Kamal in the Hamburg Kunst-Nah gallery in Germany.

Distance to the political milieu

Mohsen most definitely belongs to the liberal camp in the current struggle between secular forces and Islamists for control of the cultural sphere in Egypt. Despite this, he feels it is important to maintain a personal distance to the political milieu as a whole.

"In terms of pursuing their own interests, the opposition is not any better than the Islamists," he says. In this situation dominated by fierce extremes, he wants to be able to discern the subtle nuances.

"The situation in Egypt is not black and white. As a journalist, one has to be fair and stick to the facts. Polarization won't help us move on – we need mutual respect. Yet, no one is willing to take the risk, and that is truly worrying."

Claudia Mende

© Qantara.de 2013

Translated from the German by John Bergeron

Editor: Lewis Gropp