More than Religious Symbolism

Friday has become the most important weekday in the Arab world. Instead of being simply a day of worship and rest, it has evolved into a very special day for the "Arab Spring". For regimes in the countries concerned, Friday has now become such a cause for concern, rulers wish they could strike it from the calendar altogether.

After starting out as a jour fixe for mass demonstrations calling for greater freedoms, it has in the meantime also become a unit of measure, with dictators calculating how many more Fridays they can hope to stay in power. In addition, a reciprocal relationship between revolts as a means to liberation and religion as a means to incite revolts has manifested itself – if only externally, as Fridays became a symbol of those revolts.

Religion as a unifying factor

The choice of Friday is all the more significant for Arab societies, as it means that crucial questions are thereby addressed – in particular that of the relationship between religion and daily life, the understanding of Islam as one of the fundamental components of identity and as a unifying, not divisive factor: not just in the sense of monotheism, but also national unity.

Moreover, it has become increasingly evident that the mosque, following its marginalisation and the withdrawal of its political powers since the rule of the Umayyad Caliphate 12 centuries ago, has now been reassigned a role that was thought to have been lost.

The Egyptian Revolution of 25 January represented the clearest example of the role of the mosque and in particular of Friday as a model full of irony. The model lies in the fact that the revolution was a concern for the masses, in which traditional political organisations did not play any leading role (even though they were undeniably present in some form), and the irony in the relationship between revolution and Friday, for two reasons:

Firstly, because there is a large Coptic minority in Egypt and secondly, that the Copts accepted Friday as a day of rest in full awareness of its holiness for Muslims. They could have, for their part, insisted on the Sunday, something that would have weakened the dynamic of the street.

The acceptance of Friday manifested itself in the involvement of Coptic spiritual leaders in Muslim Friday prayers and joint Christian prayer services held by both Copts and Muslims on Tahrir Square – which for its part became a unifying factor without an overbearing impact.

The Egyptians tried to make Fridays a jour fixe in their efforts to attain freedom, and gave the day attributes such as Victory, Anger or Farewell. History will record all these descriptions as stages on the path to ending the tyranny. And it was not long before Friday fever and the symbolism of this day progressed to other countries, in particular Yemen and Libya.

Much more lies beneath the surface of these superficial details. Friday became the day that the people's assembly convened, a regular and pre-determined date irrevocably honoured like no other modern representation of the people before it. This is a people's assembly that doesn't take a holiday, unlike certain official parliaments that prescribe themselves different vacations every year, thereby not infrequently making life difficult for those who voted them into office.

Love, Brotherhood, and Politics

It is an appointment determined by God for his servants, a date upon which they should not trade (neither in a business nor a political sense), but come together to regulate two things: Firstly – for the entire remainder of the week – their relationship to God and an adherence to the teachings of love and brotherhood, reflected in interpersonal relationships such as reciprocal visits or caring for the sick and the poor.

Secondly, Friday is a day upon which the faithful are instructed to look to the society in which they live, and address its political, economic and social concerns. The first aspect is distinguished by the relationship between man and creator. This is highlighted especially clearly on Friday, a day that primarily builds upon this relationship through prayer. The second example concerns the relationship between people and their ruler, whether he be just or despotic – a social relationship that extends to non-Muslims.

In the early days of Islam when a regulative state had not yet been established, the mosques served as a weekly gathering point for non-Muslims, Christians, Jews and their Muslim rulers, thereby giving the people an opportunity to voice complaints and demands – or embrace Islam.

Liberating the Mosque from state power

Friday's role in the Arab revolutions has a fundamental significance. This lies in the liberation of religion from the influence of political power and in the re-appropriation of the mosque by Muslims. The mosque has regained its status as an arena for the regulation of matters affecting the community.

It is no longer simply a house of prayer, or a place where rulers intervene and demand expressions of homage, no matter how much of a despot that ruler may be. This was the original purpose of mosques, after the Umayyads had usurped political power and established the first "modern" mosque in Damascus.

The construction of a magnificent mosque was a shrewd move, to domesticate it and turn it into a dependent institution, with Imams and preachers appointed by the state. While prayer leaders had previously received religious instruction and led prayers on a voluntary basis, this figure was recast as an official civil servant who addressed the people in his Friday sermons and on public holidays on behalf of the state and according to its guidelines.

Tahrir Square as a "mosque for the masses"

The strongest evidence of the role of the "liberated Mosque" in current events has turned out to be in Libya. In eastern Libya, it was the mosques that called the people to battle in the first instance, after Gaddhafi began using his own ministry to keep the mosques in check.

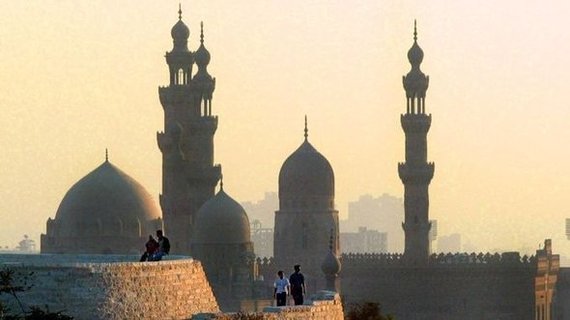

And in Egypt it could be observed that the central Islamic institution Al-Azhar in Cairo supported the revolution only half-heartedly or at best hesitantly, for the very reason that it was an official organ, whose functionaries were civil servants.

Al-Azhar missed the historic opportunity to embody the return of an open Islam, one that stands in interaction with society, by shrinking back from supporting the peaceful revolution in Egypt.

Instead, Tahrir Square in the heart of Cairo became something akin to a mosque for the masses, for its part preserving the particular significance and status of Friday, and more: the faithful streamed onto the city's central square for Friday prayers. This symbolism was not lost on anyone: religion is a tolerant matter for all, and all religious rituals only make sense if they are practised in absolute freedom.

As this example shows, attending Friday prayers is not just a pious duty, but also an invitation to gather out in the open – without spatial constraints as a symbol of despotism.

This also results in a new appreciation of the mosque in the light of freedom and power: a mosque can be out in the open, because it concerns itself with the everyday lives of the people, and if millions of people gather on the street to fulfil a religious obligation (and at the same time demand freedom), they thereby demonstrate an unshakable force, and no ruler should make the mistake of believing that he can quash that momentum.

Detached from everyday life

The keepers of political power have always tried to deny the mosques their role as inciter and provocateur, and to control this role in many different ways. The situation got out of hand in Libya, especially in the cities of the east of the country.

In one extreme case in the 1980s, worshippers were arrested for simply arranging to hold morning prayers with other people. This was enough to arouse suspicions of membership in an Islamic group. In other Arab states, the dominant view was that mosques had nothing to do with everyday life, and that they were simply and exclusively there to host prayers.

Recently, religion has again adopted its natural role as an establishment that is tolerant and admonishes freedom, just as it did when Arab people fought for their independence from colonialism. Back then, the call to fight against the occupiers in Algeria found its echo among other places in Tripoli, and the voice of the Imams of Palestine was once louder than that of the Arab nationalists.

The observation of Friday's symbolism and the role of religion in public life should not be an attempt to put a religious stamp on the Arab youth revolts or to religiously instrumentalise them, on the contrary: they should merely prove that official institutions and the state are basically against religious freedom, and only allow this in accordance with the current state of political interests.

Mustafa Fetouri

© Qantara.de 2011

Mustafa Fetouri is a Libyan journalist and head of the Libyan Academy for Higher Education in Tripoli. He was awarded the renowned Samir Kassir Prize for press freedom in 2010.

Translation: Nina Coon

Editor: Lewis Gropp/Qantara.de