An All-time Low

"The rats did this," announces the Libyan government official suddenly to the foreign journalists he has brought to a burnt-out police station in the city of Az Zawiyah, 40 kilometres west of Tripoli.

Blackened ruins that three months ago housed Libya's police and intelligence services are now a common sight all over the country. Interpretations of what it was that caused the destruction tend to vary, however, depending on where you are and whom you talk to.

Rats everywhere

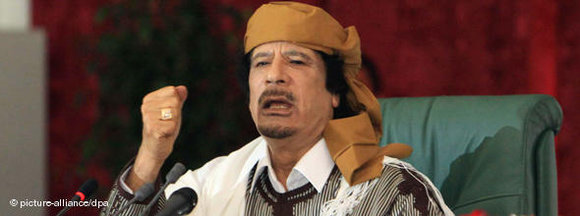

In a city such as Az Zawiyah, where Gaddafi is in control, metaphors from the animal kingdom tend to be the most popular choice of insult to direct at those perceived to be responsible, as the Colonel himself demonstrated in his most recent speech. The insurgents, he explained, are rats, rats who are being paid by France or by the US, or al-Qaeda rats; but definitely one or the other. Their aim was to undermine the "Jamahiriyya" (state of the masses), but their destructive plan has been thwarted.

The moment foreign journalists turn up at any scene of destruction, such as that presented by the central square of Az Zawiyah, they are quickly joined by a small group of young and old Libyans who will immediately launch into the current popular chant: "Allah, Muammar, Libya – nothing more." Not only politically, but rhetorically too, the remnants of Muammar Gaddafi's Libya have reached an all time low.

In those areas where Gaddafi has failed to re-establish his power following the national uprising in the middle of February – i.e. in the entire eastern part of the country, in the city of Misrata and in the Nafusa Mountains, close to the Tunisian border – the explanation for the burnt-out police stations is rather different.

Here, such ruins are seen as symbols of a tyranny that has ended ("zhulm at-taghiya"). In cities such as Tobruk or Nalut, rebels with Kalashnikovs slung over their shoulders lead journalists through the blackened ruins and eagerly point out the former torture chambers, tell of reprisals carried out against police chiefs or of the capture of weapons.

A deeply divided country

Libya is a deeply divided country, and as long as Gaddafi holds on to power in Tripoli, it will remain so. This has become clear to the dictator at the latest since the French air force strikes put paid to his attempt to reconquer the eastern rebel stronghold of Benghazi and the UN Security Council authorised NATO to use military force to protect civilians.

His goal now is to consolidate his grip on the area under his control, including the oil ports of Brega and Ras Lanuf. The increasing ruthlessness of his attacks on the beleaguered cities of Zintan and Misrata, evidenced by his bombing of fuel tanks in Misrata and the rocket bombardment of a hospital in Zintan, indicates his determination to have those cities as part of his territory as well.

Of course, it is difficult for a leader for whom "greatness" has always been what really mattered, to accept and openly admit to such a reduced objective. So now, in his own special way, he has set about preparing the people within his sphere of influence for this. At tribal gatherings in Tripoli and during rallies in front of the government compound in "Bab al-Aziziya" or on state television, Gaddafi roundly condemns what he refers to as the "imperialist, crusade-like partition plans for Libya".

The "king of the kings of Africa" goes on hammering home his message to his remaining supporters that the international force is intent on dividing Libya. It allows him to portray his strategy for holding on to power as a malicious plan being pursued by the international community that has intervened in the country.

Saddam as role model

Gaddafi's realpolitik is based on some rather successful role models. Saddam Hussein successfully hung on as dictator in Iraq for all of twelve years in spite of no-fly zones and tough sanctions.

Omar al-Bashir, former autocratic ruler of the largest territory in Africa, was forced into relinquishing de facto control over Darfur as well as de jure authority over southern Sudan. In spite of an international warrant for his arrest, he continues to reign supreme in Khartoum. By developing close ties with China, and to a lesser extent with Russia and Iran, Bashir has even succeeded in making himself economically independent of the West. Could Gaddafi pull off something similar in what remains of his Libya?

There are several factors that suggest he won't manage such a feat. The Libyan rebels are putting up fierce resistance in Zintan, Misrata and other areas of the country. They want to rid the entire country of the Gaddafi regime. Revenge is a chief motivation for their fight as they seek retribution against Gaddafi for his violent reaction to what began as peaceful anti-government demonstrations three months ago.

There are no separatist movements either in the East, "Cyrenaica", or in the Nafusa Mountains where the majority Amazigh population lived before their mass exodus to Tunisia. The insurgents want to have a unified country, but one without Gaddafi and his sons.

NATO's air strikes and naval blockade are further reasons to doubt Gaddafi's chances of staying in power. NATO's search for a meaningful role has been going on for years, albeit without much success. They may just possibly have found it in Libya. UN Security Council Resolution 1973 justifies the NATO deployment with the need to protect civilians.

Waging war against his own people

Mid-March brought an urgent need for this protection to be exercised for the benefit of the people of Benghazi, and the past three months have seen constant NATO activity around Misrata and the Nafusa Mountains for the same reason. Gaddafi is waging war in those areas against his own people. In the eyes of the International Criminal Court he is suspected of committing crimes against humanity. In this respect, the reasons and the justification for the operations carried out by the international forces in Libya are different from those that applied in Iraq and in Afghanistan.

In Iraq, the US and its "coalition of the willing" were fighting a classic war of conquest, the aim being to increase their strategic influence in the Middle East and to safeguard economic resources. Lies about Saddam Hussein's alleged possession of weapons of mass destruction were used to justify the war.

In Afghanistan, it is the US and NATO who are leading the "war on terror." The catastrophic lack of success over the past ten years on the one hand and the raid by US Special Forces that killed Osama Bin Laden on the other suggest that war is not the way to defeat organisations such as al-Qaeda. Police and intelligence work along with targeted operations like the one in Abbottabad are more effective. This was true even back in 2001.

Prospects for democracy for Libya

If the NATO states can make this point clear – it is, in all likelihood too late for Germany – the alliance may even rediscover its purpose and find its raison d'être in Libya. And if they succeed in a credible manner in protecting the civilian population from a man the German writer Stefan Weidner describes as "one of the last great villains of the twentieth century" and, if they can do so indirectly, without occupying the country, and help bring about a transition to a different political system, NATO may even be able to win back its lost credibility in the Arab world. All of this should be motivation enough for a determined continuation of the international intervention.

So things are not looking good for Gaddafi. But is this in itself sufficient to improve the country's prospects of a democratic, constitutional future? Not necessarily. The longer the war and division within the country go on, the more the civilian nature of the original protest is going to become obscured and the more likely it will be that the outcome of this revolution will be dictated down the barrel of a gun.

It is to be hoped, therefore, that the opponents of the regime who spearheaded the establishment of the Libyan National Transition Council in Benghazi at the end of February will be able to maintain or even increase their influence and help them to shape Libya's political future in a positive manner.

Stefan Buchen

© Qantara.de 2011

Stefan Buchen is currently working in Libya as a correspondent for Germany's ARD television channel.

Translated from the German by Ron Walker

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de