Reeling with desire

The study of Islamic Persian-language poetry of the 13th to 15th centuries requires not only an interest in the day-to-day realities of the period, but also a detailed perusal of poetic form.

An essay by the British poet and translator Dick Davis called "On not translating Hafez" sheds light on the difficulties associated with such an undertaking. Namely that the "language of religious or mystical devotion" in which this lyric poetry is composed is frequently far from its literal meaning. Therefore, he adds, a reader who does not come from this tradition can find it difficult to understand the original intention of the words.

He also mentions another factor which makes translating Persian poetry difficult: the language has no gender-specific pronouns, meaning it is grammatically impossible to tell – assuming the words relate to an individual – whether the poet is talking about someone of the male or female sex.

This subtlety can be deduced from the phrasing of details, if at all, or from the context of the poet′s life (insofar as this is known). The latter, with the exception of Zahir al-Din Muhammad Babur′s lyric poetry, is only seldom the case. Babur is the only ruler of the Islamic Middle Ages to have left a work in which the narrative truth largely corresponds to his social reality.

Zahir al-Din and Jalal al-Din

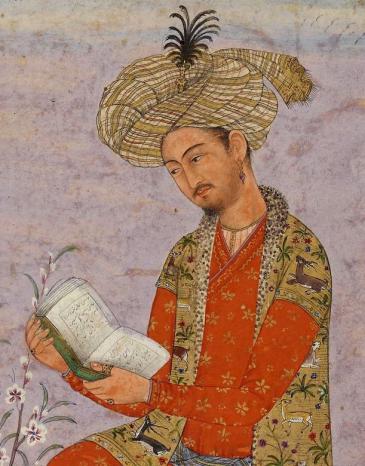

The language of Zahir al-Din Muhammad Baburs (1483-1530) is precise, direct and exceptionally detailed. The one-time founder of the Mughal empire, descended from Timur on his father′s side and Genghis Khan on his mother′s, left not only a wealth of lyric poetry to posterity, but also an autobiographical work, the "Baburnama".

It is exceptional both in terms of the style – he wrote his life story with Tolstoian realism, in the first person – and in the way his poetry is integrated into the narrative flow of the autobiography, often with contextual explanations.

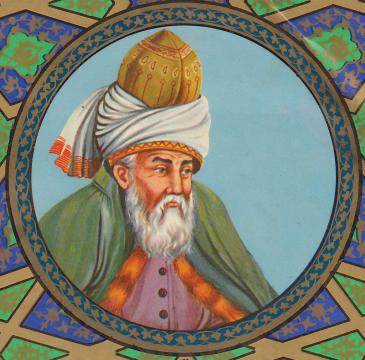

Whereas the 21st century reader stumbles over the verses of Jalal al-Din Rumi (1207-1273), not really knowing the nature of the obstacles in his way, Babur′s phrasing is clear and unambiguous. The lyric material we have from Rumi may be many times richer – academic publications on the poet, who was declared a universal cultural icon by UNESCO in 2007, are still appearing thick and fast – but there is much about him that people disagree on.

The poets are linked by their origins in Transoxiana, an area covering modern-day Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Kirgizstan and the south-west of Kazakhstan, as well as by their homoerotic poetry, which both men composed throughout their lives.

Homoerotic poetry was socially accepted

When we speak today about homoerotic love in Islam, it has little, if anything, to do with the concept that was widely accepted in the pre-colonial period. Apart from the fact that the term "homosexuality" is intrinsically bound up with the Euro-American history of ideas and therefore rests on a specific cultural tradition – meaning it has no claim to universality – homoerotic tendencies in the Islamic Middle Ages were not seen as reprehensible. In poetry, they were regarded as practically integral to good style and must therefore be investigated separately.

Praising young boys for their beauty and erotic effect was on a par with praising God. The division between hetero and homo is something Franz X. Eder describes as "a phenomenon specific to modern, Western cultures."

By implication, this means that individual love was not subject to the same social discourse in the Islamic Middle Ages, because it didn′t have to be. It was only under colonial influence that the homoerotic poetry composed in the Islamic world was treated as something indecent and categorised in a correspondingly negative way.

Alongside the widespread conviction that the masculine form reflected divine perfection, homoeroticism was preferred over heterosexual metaphors due to the established separation of the sexes in society. Marriage, too, had a different status. Marriages were often made on the basis of favourable alliances, while love was often found elsewhere.

The 17-year-old Babur first describes his amorous feelings when, shortly after his marriage in around 1500, he catches sight of a beautiful boy named Baburi in a bazaar in Andijan.

A few lines previously, he details the aversion to intimacy with his new wife that is consuming him: "[...] from modesty and bashfulness I went to her only once in ten, fifteen or twenty days. My affection afterwards declined [...] my mother the Khanum used to fall upon me and scold me with great fury, sending me off like a criminal to visit her once in a month or forty days."

By contrast, he became lovesick at the sight of the boy Baburi: "Up till then I had had no inclination for anyone." And when he finally stands before him, he is rendered speechless, crippled, and he notes: "Desire overwhelmed me, made me reel / What every lover of a comely face does feel."

Such verses and prose passages are hotly debated by academics. Stephen F. Dale, a professor of history, doesn′t rule out the possibility that this may be "life imitating art", a literary exercise. On the other hand, nowhere is it easier to grasp the sense and intention of a verse than in Babur′s "Baburnama", where the author immediately provides the context of the verse′s composition.

Eroticism in Rumi′s poetry

Eroticism and sexualised symbolism in Rumi′s "Mathnawi", as Mahdi Tourage writes in his book "Rumi and the Hermeneutics of Eroticism", have attracted little attention until now, having been something of a Cinderella subject among academics. Still, given the great variety of interpretations, it is important to both examine and question these themes. According to Annemarie Schimmel, it was only Shams-i-Tabrizi who first transformed Jalal-al Din Rumi into a poet. She even goes so far as to claim that we would be talking about a different Rumi today if the two had never met.

She may compare the two men′s relationship with the friendship between Gilgamesh and his Enkidu, but she does not touch upon the lasting effect of the union. In fact, it can be said with a fair degree of certainty that it was only after the disappearance of his beloved Shams that Rumi began to engage intensively with poetry. In an ideal world, the work he left to posterity would be attributed to individual love, but instead the way it is usually categorised means that the case for it being homoerotic poetry is often vehemently denied.

Jalal al-Din Rumi and Shams-i-Tabrizi met for the first time in 1244 – and after that, they never left each other′s side. Dogged by jealousy and resentment from Rumi′s family and followers, one day Shams finally disappeared. The background and the causes of his absence are not known. After the loss of his beloved Shams, Rumi tirelessly wrote letters, travelled to Syria and exhausted himself in the search for him. What we read with such delight today can largely be traced back to this period of Rumi′s life.

Melanie Christina Mohr

© Qantara.de 2017

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin