An uphill struggle for Tunisiaʹs Amazigh

Tunisian Hisham Ghrairi defines himself as "Amazigh" or Berber, descended from North Africaʹs original inhabitants, but he did not learn his native language easily, either at home or at school.

Hisham was born in 1980 in southern Tunisia at a time when the Amazighs were forbidden to speak their own language, to the extent that families even spoke Arabic at home. As Hisham says: "Tunisiaʹs people became Tunisians," referring to the approach of former President Habib Bourguiba, who sought to impose a "single identity", without regard for the countryʹs ethnic diversity.

Under the shadow cast by this vision, families didnʹt talk about their Amazigh identity; indeed, it was hidden away as a "source of shame". Families didnʹt converse with their children or even teach them their own language. "Like most people, they didnʹt want problems and they feared for their childrenʹs safety," Hisham explains.

Despite this, curiosity led him to inquire about the origins of his family. From there, he began to mix with students from neighbouring villages who only spoke Amazigh and from them he picked up a few words and phrases. Later, he got to know a group of foreign young women who were studying Amazigh culture in peopleʹs homes and they introduced him to his original culture.

The imposition of "a single identity"

When Hisham, who used to work as a tour guide, tried answering touristsʹ questions honestly, confessing that the state forbade them from speaking in their own language and celebrating their own cultural occasions, he got into trouble and lost his job in tourism.

In his view, the state wanted the Amazigh to be a ʹcommodityʹ, a ʹTunisian artefactʹ, forgetting that "this commodity is comprised of people who are indigenous to North Africa and who have rights." Today Hisham tells his story freely, sitting in a cafe in Matmata in southern Tunisia. The village still welcomes visitors, accommodating them in small hotels that preserve Amazigh architecture.

In the wake of the Tunisian revolution in 2010, Amazigh activists began to raise their voices and demand the rights denied to them over long centuries. Re-discovering the alphabet after the revolution

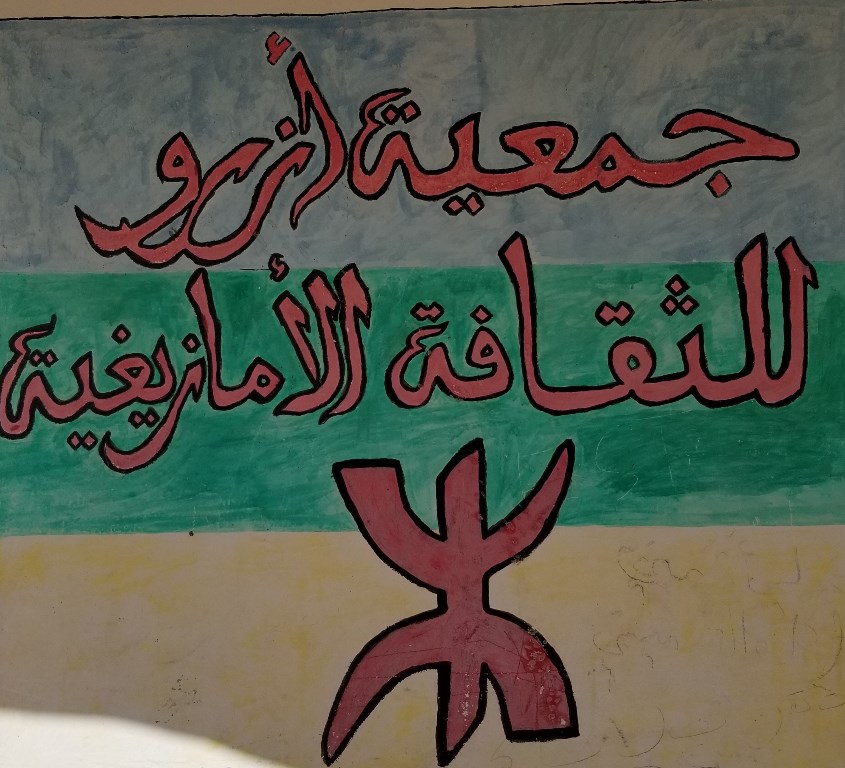

Today, a good number of Tunisian associations have begun to teach the Amazigh alphabet – Tifinagh – without fear of repercussion. From December 2012, the Association for Amazigh Culture (AZROU) based in Zrawa started offering free lessons to local youth who wanted to learn how to write Amazigh.

AZROUʹs president, Arafat Mahroug, says that the people of the region speak their language from infancy, before they learn Arabic at school. But no-one knew how to write it and that was, in his view, the natural outcome of the policies introduced by Bourguiba.

Mahroug says that his family used to live in the ʹmountainsʹ, but Bourguiba sought to "create new structures to encourage assimilation, with Tunisia the primary link between them." He adds that "the pretext was to improve services, such as electricity, water, street lighting, health and education, but the real aim was to strike at the ties of the clan, the tribe and the community, Arab or Amazigh".

In Mahrougʹs view, it was a policy that "shook you to the core", because "you were bound to forget your own language when all the services and education were in Arabic and when the people living around you were Arabic speakers who wouldnʹt understand you if you spoke Amazigh, thus forcing you to communicate with them in Arabic. In this way, Amazigh gradually disappeared, as it did in the village of Tamezret, where less than 20% still speak Amazigh".

Long decades notwithstanding, Mahroug asserts: "We stayed firm. We kept our identity despite everything and we have worked on our own development in the eight years since the revolution."

After Tunisians ousted former president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, campaigners (including from AZROU) established contact with activists in other countries in North Africa, including Morocco, Algeria and Libya, whom Mahroug contends were ahead in the field of Amazigh rights. They gained much from the Royal Institute of Amazigh Culture in Morocco, which was established in 2002 with a view to preserving that culture. Among symbols recently displayed in the AZROU headquarters in southern Tunisia “which are found in traditional tapestry and in indigenous tattooing, we discovered they were in fact letters of the Amazigh alphabet!”

Amazigh not merely a ʹcurioʹ

One of AZROUʹs activists, Ali Azadeh, has taken upon himself the job of teaching Amazigh "to anyone who believes himself to be Amazigh", wherever he may be, as the opportunity is better today than for decades to be more than just a curio for the tourists.

"Although it used to be forbidden to use Amazigh in daily life, it was employed to promote tourism, in signs, hotels and exhibitions," Azadeh added. This means of promoting tourism persisted, however, becoming an increasing source of income for ordinary people, to the extent that they themselves came to view their own culture, customs and traditions as nothing more than a commodity, as had been the case for decades before. It is this mind-set that AZROU, despite its limited resources, is seeking to change today.

To date, AZROU has taught dozens of students to write Amazigh and has given lectures at higher education institutions in the governorate of Gabes. They are limited only by the modest resources at their disposal. According to AZROʹs president, "Young people and those who donʹt have Arab nationalist, Islamist or Muslim Brotherhood ideologies welcome the chance to learn the language."

Azadehʹs passion (he wears rings adorned with Amazigh symbols), is not constrained by AZROʹs small budget, however. Indeed, he does all he can to educate anyone interested. He even taught a group in Tunis where he worked in a bakery before his retirement. He still helps with translation queries from anyone who contacts him, whether face-to-face or via Facebook.

Have the campaigners achieved their goal?

According to the records of the International Working Group on Indigenous Affairs, Tunisia voted in favour of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in 2007, but few citizens or lawmakers are aware of this, nor has it been applied in the local courts.

After the outbreak of the revolution and the emergence in public of voices which had hitherto been secret, there are now ten cultural associations in Tunisia aimed at preserving and promoting Amazigh language and culture.

For all that, the most important document in the country, namely the new constitution, which was ratified by parliament in 2014, made no reference to the Amazigh dimension whatsoever. In fact, the constitution specified Tunisiaʹs "cultural and historical belonging to the Arab and Islamic nation". Moreover, it mentioned the Maghreb Union as "a step towards Arab unity", in contrast to the new Moroccan constitution, which states:

"The Kingdom of Morocco is a sovereign Islamic state, enjoying national unity and territorial integrity, maintaining the cohesion and diversity of its national identity and united by the sum of all its component parts, Arab, Islamic, Amazigh, Sahrawi and Hassani and enriched by its African, Andalusian, Hebrew and Mediterranean heritages". Clause 5 affirms that "Amazigh is also an official language, a common asset of all Moroccans without exception".

It is worth mentioning that the writer of this piece tried to contact the Tunisian Ministry of Cultureʹs spokesperson, but without success.

Hisham Ghrairi, who left the country after losing his job as a tour guide, says that the two former regimes stripped the Amazigh people of "their most beautiful possession", namely their culture. Will the coming years see its revival?

Lina Shanak

© Qantara.de 2019

Translated from the Arabic by Chris Somes-Charlton