Tangiers – end of a cosmopolitan era

What changes has Tangier seen since the publication of your book two years ago?

Dieter Haller: There are two fundamental aspects that spring to mind. The first is the cityʹs cultural demeanour, the second its political make-up. From what I can see, the cityʹs conservative nature has become more obvious. When I was here two years ago, there werenʹt many women wearing the black burqa. Now, they can be seen all over the place. Previously, there existed a deep-seated propensity for conservatism; today conservative behaviour is a reality.

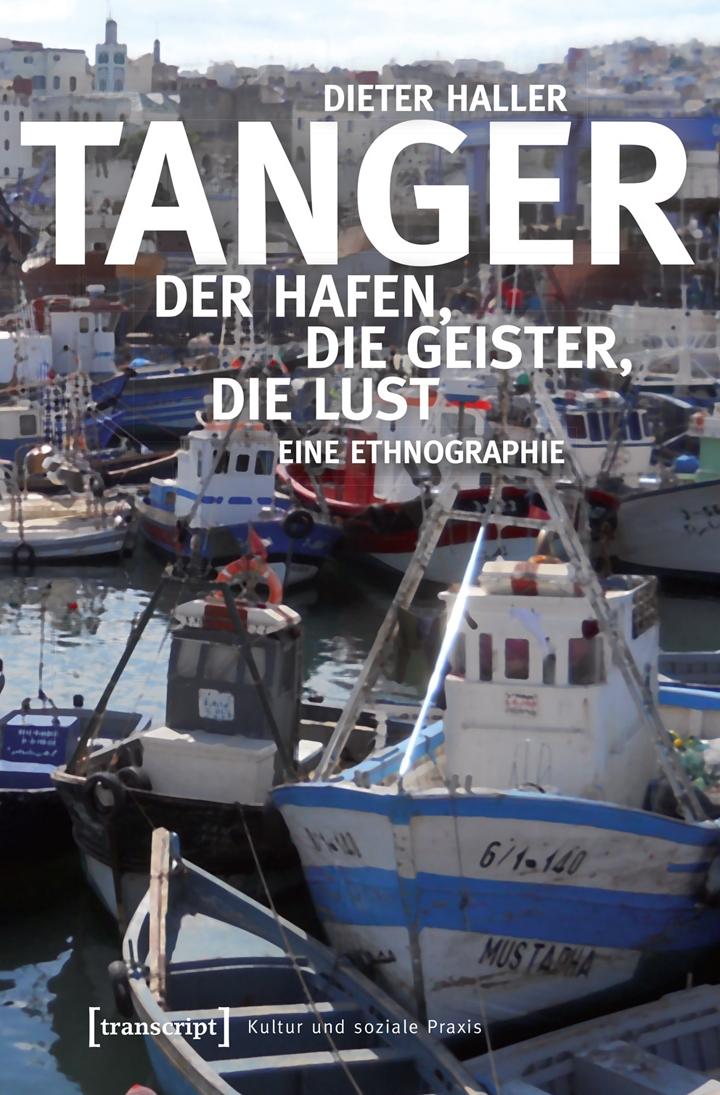

The second area of change can be seen in the buildings and the architecture, in the structure of the port, the changes along the coastline – these days, for instance, there is Tangier Marina, Tangier Beach and so forth. Moreover, it is also fair to say that the city is becoming increasingly divided. Nightclubs that were once very obvious are now hidden away.

A considerable amount of money has gone into beautifying the urban environment. Similarly, citizens have become more eager to keep their neighbourhoods clean and tidy, giving buildings a fresh coat of paint, as well as making districts greener by using plants and the like. It reminds me of Italy in the 1960s when society became both more consumer-oriented and more conservative.

Why did you choose Tangier as your subject? Why not take another Moroccan city, or one elsewhere in North Africa for that matter?

Haller: Firstly, I chose it for professional reasons, having studied in Spain in the early 1980s and gone on to conduct research in Gibraltar. At the time everyone there was talking about the border here, and about Tangier and Morocco. I said then that it was important to figure out this place and to understand the relationship between the two sides at a local level, because there are so many links between them. Secondly I had got to know Tangier through the accounts of European visitors. It was this combination that prompted me to study it.

Gibraltar is a place where different religions have long existed side by side. Everyone there used to tell me that Tangier is also an example of Muslim, Jewish and Christian co-existence. To me, this is very important: personally I have never believed in the idea of a single, unified identity, or in the division between religions. To an anthropologist, ideological rhetoric is irrelevant; what matters is what people do and how they live.

In one interview you said that you had touched upon a "taboo", related to the concept of nostalgia – the sort of nostalgia that Europeans have for Tangier and its idiosyncrasies. Can you explain this idea a bit more?

Haller: Throughout my research and study I found it impossible to untangle myself from the Europeansʹ view of Tangier and its history. I was told in Gibraltar that Tangier had been a city of co-existence long before. This considerably heightened my interest in cities that have experienced a measure of cultural and religious co-existence.

In your book, you give a voice to people with neither voice nor history – to the ordinary people of Tangier. Why did you choose them?

Haller: When I began my research on Tangier, I found American and European accounts of the city, assessments by Moroccan intellectuals, as well as official accounts about on-going projects. Whilst these accounts are important to me as an anthropologist, I donʹt have to pay too much attention to what officials and intellectuals say in their speeches; it was more important to know what people in the street were saying and how ordinary folk see the world around them.

The projects have undoubtedly helped many to find jobs, but what is a lowly sailor supposed to do, or those who hawk smuggled goods in the streets? How do they get by? Meeting people in the street is part of my duty as an anthropologist, to do my research in the field. My interest is in how things are applied, not in what is said. In the introduction to my book, I wrote that I did everything in my power to avoid meeting intellectuals. This presented difficulties throughout my research. After all, academics and intellectuals have answers to everything, while I have nothing but questions.

In your book, you say that Tangier is undergoing a remarkable transformation, seen in the clash between indigenous people and new arrivals, especially in the wake of the departure of the Jews and the Europeans. In your opinion, how did this conflict arise?

Haller: In the wake of Moroccoʹs independence, Tangier was a small town with a limited population. Both the Jews and the Christians left, leaving only the local Moroccans. Subsequently, many Moroccans also emigrated to South America and France. After that, people were drawn to Tangier from the south and from France. As we know, the original inhabitants of the city were not Francophone, but Spanish-speaking. This community soon became a minority, politically as well, without any influence over their city.

We all know from Hassan IIʹs and Mohammed VIʹs public statements that they both brought in people from other parts of Morocco to rule this region, albeit for different reasons. Meanwhile people from Tangier headed to Meknes. The goal was, of course, to create a Moroccan state. This led to the original inhabitants of Tangier becoming a minority, not just demographically, but politically too.Another factor was the arrival in the city of people from the countryside, which did not go down well with the people of Tangier. The country folk did not know how to adapt to life in the city, moreover they brought with them their customs, their cattle and their sheep. This led to a change in the cultural structure of Tangier and in the lifestyle of its people. During the attempts to subdue the region following independence, Tangier experienced a degree of marginalisation. There was no way forward economically other than by smuggling. This made a lot of people feel like outsiders in their own city.

Over the course of your studies, you met many indigenous people of Tangier who expressed discontent at the policy of "Moroccanisation". They stressed that Tangier was not a colony, but an international city and that "Moroccanisation" had obscured its cosmopolitan heritage. What do you make of this?

Haller: As regards the Muslim working class – and this is about them – quality of life was better when Tangier was an international city than it is now. For instance, they used to have the option of being treated in Jewish or Italian hospitals, or to have their children taught in Italian schools. Today, in contrast, people are always complaining about the quality of health and education. Of course, things were not perfect in the past, because Muslims have always had fewer opportunities than their Jewish and European neighbours.

Aside from the book, as a German who lived in Tangier for over a year, how do you rate the quality of life in Morocco from the point of view of freedom – personal freedom, human rights and the status of women?

Haller: Thatʹs a difficult question, because there are two sides to the issue. On the one hand, there are increasing numbers of people who speak about and demand individual freedoms through young peopleʹs music, social networking sites and so forth. They are expressing their desire for freedom more than ever. On the other hand, society is becoming increasingly conservative, with a monarch who is both contemporary and traditional at the same time.

It is extremely complicated. Morocco is a mix of people, encompassing those who defend freedoms and womenʹs rights and others who are conservatives, not to mention the official rhetoric of the state. Tangier, a case in point, used to be cosmopolitan, but it has quickly turned into a conservative city, underlining the huge difference between it and other Moroccan cities. The transformation in this respect was much greater than elsewhere. Women in Tangier used to enjoy greater freedom and homosexuals were more able to express themselves openly.

This is not only a consequence of Wahhabist Islam coming from Saudi Arabia, which has infiltrated peopleʹs minds and changed their ways of living; it is also due to the economy and the transition from a conventional and traditional society to a consumer one. Indeed, the latter has done more to make the society conservative. In my encounters with older Tangier residents, many of them said that freedom of speech has long been empty rhetoric. Hence my conclusion that the freedom experienced during the cosmopolitan era was limited to the higher social classes, most notably the Jews and the Europeans.

Interview conducted by Karima Ahdad

© Qantara.de 2019

Translated from the Arabic by Chris Somes-Charlton