The disappearance of the kiss

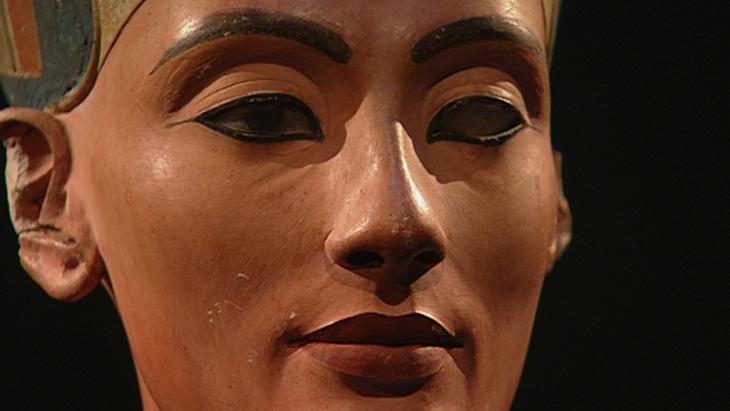

The most widely known Egyptian woman in Germany is not the legendary singer Oum Kalthoum, but Nefertiti. What role does Nefertiti play in Egypt?

Adham Hafez: The same. Nefertiti is still the symbol of ultimate beauty. The name itself means "the beautiful one has come". Together with Hatshepsut – the first queen of such power – and Cleopatra, they are the great celebrities.

But of course the history of the bust of Nefertiti is seen differently in Egypt than in Germany. The bust of the queen is not the only object of Egyptian history to be placed in a European collection outside our domain where we can't do anything about it any more, like all the obelisks in Italy and in France. There are a few in Italy where they've put a cross on the top, as if to baptise them. It is like that. They own it, they edit it – a lot of questions about cultural ownership!

In 2011, you created the piece "White Arabs / Dark Arabs". Nefertiti plays a key role in it, and at a certain point, there is a reference to how she is more German than a lot of Egyptian immigrants in Germany.

Hafez: This is a long story. The revolution had just started when I created the piece. My house faces Tahrir Square, my office as well. For the first seven months of the revolution, I cancelled all my international engagements. I refused to travel; I just wanted to be there.

At a certain point, I asked myself: what political engagement do I have with being Arab? This question did not just arise as a result of being the focus of all the European reporting, it had also arisen in Egyptian society itself. It reminded me a bit of what my parents had told me about the period of Nasser, when suddenly there were discussions about who is Egyptian and about the purity of race.

This ideological shift was about "how to be a real Egyptian and a real Arab". But I don't know how to be a real, "pure" anything. Egypt has a long history with a lot of colonisers including the Arab-Muslim history. If you say to be a real Egyptian is to be a real Arab, you could also say that to be a real Egyptian is to be a real British person, because we have also been colonised by the British.

These thoughts brought me to do a lot of interviews about aspects of national identity. Together with my team, we then deconstructed these interviews, also self-exoticising ourselves. We ended up with Nefertiti and the body politics around immigrants in Germany where there is this difference between an object representing a body and an actual body. Our dramaturge wrote a very clever speech that keeps playing with representation and history, explaining the name of the Bode Museum in Berlin as an old Egyptian word, and that "Nefertiti" means "The woman who shook her way and emigrated to Germany".

You have been invited to Return to Sender, a festival about artistic perspectives on the Berlin Conference that divided Africa into European colonies 130 years ago. A colleague of yours, the Moroccan–French artist Mehdi-Georges Lahlou, has been exhibiting a selection of queer Nefertitis – that's how we got onto this topic in the first place. At the moment, here in Berlin, "queerness" is a big theme in the art world. Perhaps there's a little shift right now from a political to a more playful approach. What about the Egyptian scene?

Hafez: There is no word for queerness in Arabic.

Nor is there in German.

Hafez: Yes, it is very obvious that Queer Studies – just like, for example, psychoanalysis 100 years ago – emerged at a certain time and at a certain place in the world, which means that everything that is published about this complex in Egypt is in English.

To what extent does the art scene deal with the topic?

Hafez: The art scene in Egypt is busy dealing with catastrophic realities such as war, victims lost in the revolution, or daily basic human and personal rights. Some works may look queer to a foreign audience, even though their creators would not describe them as such. The same is true of my work. It is the same with work that looks "resistant" or "activist" in nature, while its creator doesn't describe it as such.

There is the work of Lana Al-Sennawi, which addresses the disappearance of the kiss from Egyptian films by reflecting on documents of "historical kisses" from Egyptian film history. Shayma Aziz's "SHAME" is a wonderful example too, as a painting that stares aggressively at the observer, reminding us of the position of women's bodies in art in the past and now. There is also Amanda Kerdahi Matt's latest piece. Women were invited to smoke with her in an installation setting, and the cigarette filters collected eventually make a nicotine stained screen that she uses for projections. This becomes the "document' of her installation-performance, reminiscent of women's secret societies and informal secret gatherings that one knows about in Egypt.

Do those traditions have a certain cultural impact?

Hafez: There is a strong tradition of women gathering exclusively to chat, to support one another or do henna and other cosmetic activities. But you also have a tradition such as Zar – a kind of exorcism ritual to reconcile with demons inside you. You dance and sing the demons' favourite songs until you reach the point of exhaustion, which might mean that the "demon" is now satisfied.

It is a form of art that has been banned since the British colonial era. It is illegal both to practice and to witness it. There is only one place left in Cairo where we can see it today because they do it as a musical concert and they try their best to stop before falling into trance. It is only women who play the music. Or if it is men, it is an old man or a homosexual, and if not, they have to make him cross-dress. It's all very matriarchal. I grew up with a Zar priestess in my neighbourhood. She was so powerful that as a child, I would run away when I knew she was on the street.

In your piece "2065 BC", a deconstruction of the rituals of power, which was a success in Berlin, you work with a cast of four women. Why only woman?

Hafez: They are just amazing, and each of them has multiple talents and careers. One is the strongest bouncer I've ever seen in my life. She is a visual artist and performer, who used to work for a famous club in Cairo, and if she says no, you don't argue. Go to Berghain in Berlin and you'll see the tall guys with big muscles. She doesn't need any of that. She has her eyes and her voice and her very precise decisions. So every woman has her very special story.

As for the decision to do a women's piece, "2065 BC" takes place at the end of the world. The third world war – the ambiguous war we are already in – has happened. Something has to change. So, men aren't allowed to rule anymore. But this doesn't make it a feminist piece. It is not about who rules the world but about how we do it. If you are driving a bad car, it will crash. Men, women, queer or not. So let's use that car that always crashes and let women drive it and see what happens. In that sense, I wanted to raise the gender question to deal with fallen tools and strategies, with clarity that comes from displacement, but not take it as a solution. Because the solution is much deeper than a shift in genders.

Interview conducted by Astrid Kaminski

© Qantara 2015