When writing becomes a crime

Why did your case attract so much media coverage?

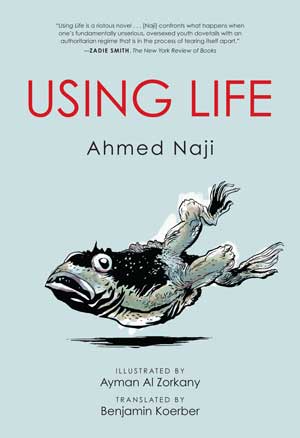

Ahmed Naji: The case was about a guy writing a book and being thrown into jail because the court found that said book was destroying public morals. It was the first time something like this had happened in the history of the modern Egyptian judicial system. Apart from that, what was special about the case was that it included sex. For newspapers, any news related to sex is interesting.

But there are other books that deal with sex.

Naji: Indeed, nor do I really see myself as someone intent on crossing red lines. However, in 2015, the general prosecutor issued an order to open every pending case against any journalist. The other journalists had mostly been accused of insulting the president or the government. My case was an opportunity for the prosecutor to appear as a divine adjudicator of public morals.

Do you think that public morals are a substitute for religious morals?

Naji: They are, of course, connected. Sisi goes on about public morals because he does not want to appear to be fighting Islam. For instance, he always shows his wife wearing the hijab. He does not talk about religion – but he talks about public morals.

A committee investigated whether your book is fiction or non-fiction. How did they try to establish that?

Naji: The prosecutor treated my book as if it was a newspaper article, just because one chapter had appeared in the literary magazine Akhbar Al-Adab.

One scene describes how the main character takes drugs and my name was written under the text. The prosecutor threatened to either charge me for drug abuse or to charge the editor for publishing fake news.

In the official investigation case report, you find a hilarious question that the prosecutor asked the editor-in-chief. It reads: "What do you know about the relationship between Ahmed Naji and Lady Spoon?" Lady Spoon, or Sayyida al-mal‘aqat, is the name of one of the fictional characters in the book.

The language in "Using Life" is not very common for novels. Did you anticipate that the book and in particular the language would cause you trouble?

Naji: I am not a writer of bestsellers; I know that I write difficult books. The lawyer who defended me based his argument on an article of the constitution prohibiting the imprisonment of a person for any artwork or creative writing. The judge commented, "Writing has to be beautiful and to support public morals. What Ahmed Naji wrote is not art because he does not use metaphors."

A sex scene described by the writer Alaa Al-Aswany, for example, is always massive. It could be a homosexual sex scene. But it is full of metaphors which describe how the woman felt; as if a flower was opening inside of her, how he touched her fruits and drank the honey between her legs. I do not use such metaphors. But I might start a paragraph in very old, classical Arabic and continue in heavy dialect, or in a modern style.

Do you believe the verdict was about the content of the book or rather about oppression and limiting the freedom of literature?

Naji: We asked people in the Egyptian intelligence service if they were behind this case. They said no. So, basically, the case came from the judiciary. The Egyptian journalist syndicate raised a case against the public prosecutor at the majlis ad-dawla, the State Council. The State Council admitted that it was wrong that the prosecutor jailed journalists. But the Council does not have the power to make the prosecutor obey; he is to a certain degree independent.

This is the problem with the Egyptian justice system. It may be independent, but it has too much power. No one can control it. Firstly, the current president, Abdul Fattah al-Sisi, imposed a state of emergency. Then Adly Mansour and the judiciary created a system called "Al-Habs al-Ihtiyaty", or "preventive detention". It is just one of the disastrous problems facing our country at the moment. In prison, I met people who had been waiting for a hearing before the judge for 25 months. Egyptian prisons in Egypt are full of such individuals.

Many intellectuals went to court and spoke in your favour, didnʹt they?

Naji: I experienced huge solidarity from Egyptian, Arabic and international writers and intellectuals. A couple of weeks after I was imprisoned some talked to Sisi about my case. Sisi gave them permission to appeal before parliament. They even collected over 100 signatures from members of parliament in favour of the necessary amendment. But the Ministry of Justice turned it down.

Would you say that your case basically reflects the struggle between Egyptʹs executive and the judiciary?

Naji: State sovereignty is itself divided. The military have the upper hand; they can push everyone to do what they want. After all, the military are armed. But there are other powers that have always been in conflict with each other, for the simple reason that each institution is striving for domination.

Moritz B. and Luisa M.

© Qantara.de 2018