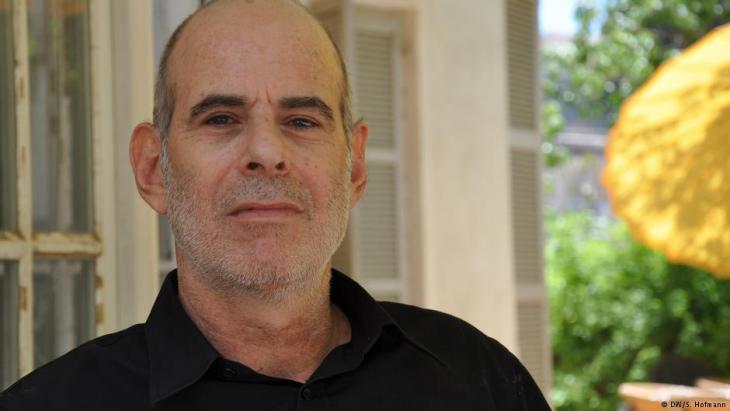

Israeli "Foxtrot" pulls no punches

Your film "Foxtrot" starts with a situation that is probably the most terrifying moment for every parent in the world: the message that their child is dead. Why is this still a very specific Israeli story that you tell?

Samuel Maoz: When your son serves in the Israeli army and there is a knock on the door, you open the door and see an officer, a female soldier and a doctor; they don't have to say anything. It is quite clear what has happened and this is the most terrifying moment that every Israeli parent is afraid of. Every woman and every man here has to serve in the army.

Have you experienced such a moment in your family?

Maoz: There is a personal aspect to it, but it's different. When my eldest daughter was going to school, she was never on time. And in order to not be too late, she would always ask me for a taxi. This habit started to cost us quite a lot of money and I felt it to be bad practice, so one morning I got really mad and told her to take the bus like every one else. If she was late, then so be it.

About 20 minutes after she left, I heard on the radio that a terrorist had blown himself up in bus number five — the one that she had to take — and that dozens of people were killed.

I tried to call her school, but the communication centre had collapsed. After an hour she showed up at home. She had been late for the bus, but only by a few seconds. She saw it in the station, started to run and waved her arms, but the bus left the station and she took the next one.

You know, I was a soldier in the first Lebanon war, I fought in bloody battles, but this one hour was the worst hour of my life.

In Foxtrot I wanted to explore the gap between things that we can control and those that are out of our control. This was my first stimulation, the core of the feeling of the film. But there was another motivation ….

Which one?

Maoz: I have to go back to my first feature film, "Lebanon". It's my personal story, my war experience, from my physical point of view as a gunner in a tank, but also from my emotional point of view as a 20-year-old child who had never been involved in any act of violence, then one morning found himself deep in hell, in bloody battles killing people.

I knew there was no way out, I had to kill, otherwise I wouldn't be sitting here now.

But the fact that I did it made me feel guilty – still today. I never got psychological treatment, but I know that I was suffering from a small, silent post-trauma.Is filming your therapy?

Maoz: It wasn't the motivation, but it was a huge and surprising by-product to understand that I am creating the best treatment myself. In that way, I was lucky.

In "Lebanon" I talked about myself, but after the film came out I realised that I wasn't alone like I had thought for so many years; that the Israeli society produces many versions of me, too many. So, I asked myself, why do we – the Israeli society – behave the way we do? Thatʹs the big question of "Foxtrot".

The simple and complex answer is that we are a traumatised society. The emotional memory from our past trauma, the Holocaust, followed by our survival wars – this memory is still stronger than any current reality or logic. The trauma passes from one generation to the next and is based on the determination that we are in a constant existential danger and as a result, in a never-ending war.

But nowadays, our technological country with nuclear weapons is not in any existential danger, no more than any other country. Our traditional enemies are no longer relevant.

But there are new enemies …

Maoz: Ok. I don't say we don't need an army at all. But you cannot compare the situation today to the Holocaust and we still continue to treat this danger as if it were the same.

We just bought three submarines — from Germany, by the way — instead of feeding the poor in our country. Submarines against whom? Against Gaza? We already have submarines and a huge army. We don't change the priorities because of this trauma. And the politicians ride on this horse.

In Foxtrot, the trauma passes from the German grandmother, who survived the Holocaust, to the son, who fought in the Lebanon war, to the grandson, who commits a terrible crime while serving at a checkpoint in the occupied territories.

Maoz: In the film Michael and I are the second generation of Holocaust survivors. My mother was a Holocaust survivor from Poland.

Our main problem was that we couldn't complain about anything. Our parents and our teachers had survived the most terrifying trauma in modern times and they were naturally not very stable coming out of it. They waved with the numbers on their arms and shouted all day long that they had survived the Holocaust, and who were we, spoilt children born in a sunny country with the blue sea and oranges; who were we to complain?

Everything was about the Holocaust. It was ridiculous. When I went to school and I got a seven in maths, my mother would say: "I survived the Holocaust for this? For a seven in maths?"

When I came back from the war with two hands, two legs, no burning marks on my skin, complaining that I was hurt, it was unacceptable. "Come on. Be a man. Overcome. We survived the Holocaust."

What about the next generation? The snipers at the Gaza border – where over 130 Palestinians were shot in the past weeks – are about the same age you were when you went to Lebanon. How do you feel about them?

Maoz: These soldiers are also victims in a way. They are children. In the army, they brainwash you. I never blamed the soldiers. They are just the executors. It's very easy to give a child a gun, but he is not the killer; you are. These kids will suffer. Maybe not now, but 10 years from now. They will understand what they did. Society produces another traumatised generation.

How can this vicious cycle be interrupted?

Maoz: Perhaps the conclusion of the film is that fate cannot be changed. Not because it's divine, but because the nature of the traumatised Israeli man will shape the collective.

The little step that can save us from the loop of the foxtrot must be done by some brave leader. We once had one: Yitzhak Rabin. But he was murdered and the dream of peace was murdered with him.

In an interview a journalist told him that the majority of the people in Israel wouldn't want his peace plan. He answered: "So, the majority is wrong." From time to time, you need a shepherd who understands that the people are not necessarily right.

The Israeli culture minister, Miri Regev, condemned the film for defaming "the good name of the IDF (Israel Defence Forces)" because young Israeli soldiers kill the passengers of a car and cover the traces of their act in the film.

Maoz: She had already attacked it before the film was released – she hadn't even seen it. It's not a documentary, so it is not obliged to reflect some objective truth. Its truth is dramatic and artistic.

But the fact that I dared to criticise the army that liberated us from our past trauma, our salvation angel, made me a traitor to many in Israeli society. The fact that I fought in the Lebanon war and paid a high price has no value anymore. I am a traitor because the minister of culture announced it to be so. She incited a large public who has not seen the film.

The bottom line is that her attack actually confirmed the film's statement. In the beginning this was a kind of achievement for me.

When did this feeling change?

Maoz: In many ways she helped to stimulate the debate that the film wanted to evoke, but personally it became different when I received threats. Someone wrote to me: "If you leave your flat" – and he wrote the correct address – "I will wait for you to throw acid in your face. I want you to be blind. I don't want you to be able to make films anymore."

Also the usual stuff: "We saw that your family wasn't killed in the gas chambers, we will create a gas chamber for you, your family and all these left-wing creatives that live in Tel Aviv." There is no red line anymore. In the beginning I went out with sunglasses. But not anymore.

Will your next film still be critical about the Israel?

Maoz: I'm finished with the army. At least for now. My new film is a women's film about a mother and her daughter. A strong humanistic drama without any political messages. It's about basic values in life.

I don't know how to say it without sounding pathetic, but I really believe that every human society should strive to be better. And the necessary condition for improvement is the ability to accept self-criticism.

But when critics are considered to be traitors, you have no chance of rising. When I criticise the place I live in, I do it because I worry, I do it because I want to protect it – and mainly I do it out of love.

Interview conducted by Sarah Judith Hofmann

© Deutsche Welle 2018