Europe’s coloniality persists after the fall of empire

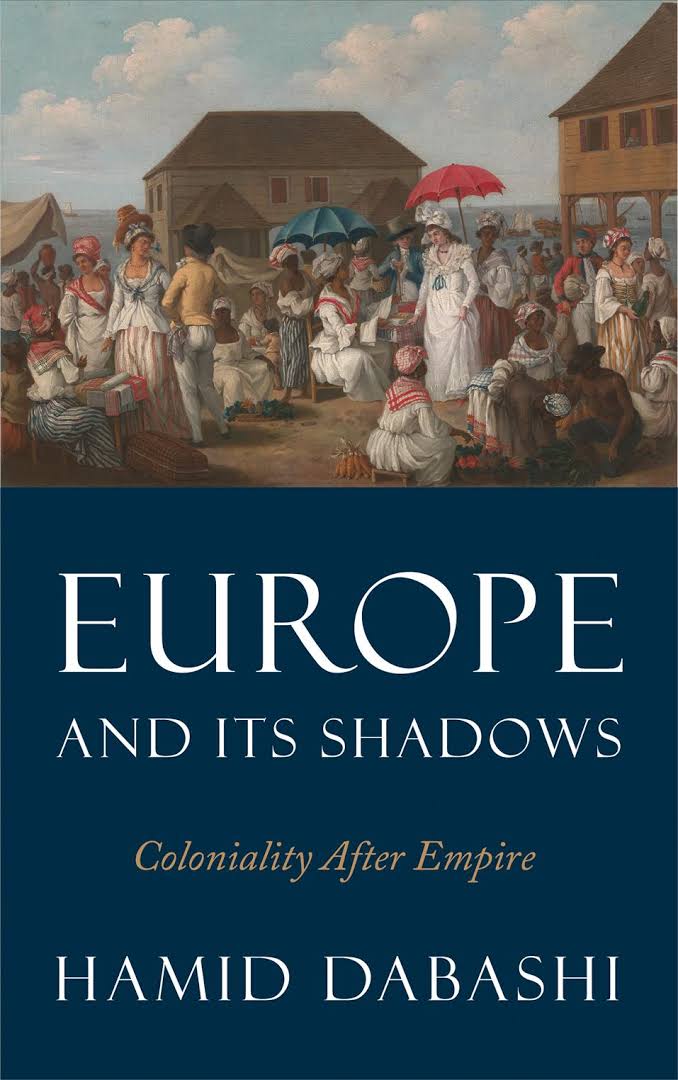

One of the most renowned scholars of postcolonial thought, Hamid Dabashi has created an archive of influential books and articles. His new book "Europe and its Shadows: Coloniality after Empire" deals with Europe as an allegory and traces "how the condition of coloniality persists even after the collapse of empires." Dabashi’s previous books include "The Arab Spring: The End of Postcolonialism" and "Can Non-Europeans Think?".

***

Mr Dabashi, what made you write this book?

Hamid Dabashi: The entirety of my work is interrelated. One mind: multiple shades. Nothing in particular "makes" me or "compels" me to write any book. For that sort of writing I am blessed to have a voice in my Al Jazeera columns with a magnificent global audience that cares to know what I think of our current compelling issues.

In my books I have an entirely different, far more fundamental and upstream body of thinking at work. They are like the physics to the engineering I do in my columns. This particular book is part of my continued reflections on the possibility of a level playing ground for former colonies and current post-colonies in a world that has hitherto denied them any such justice and fairness.

In "Europe and its Shadows: Coloniality after Empire" I go for the real thing, not the fact or phenomenon of "Europe", but its very allegorical power. How did it start? How does it work? Why are we mesmerised and repelled by it at one and the same time? My prose is neither Europhiliac nor indeed Europhobic. It is in a way very surgical. I want to know why and how the condition of coloniality persists even after the collapse of empires. That is the reason you see the word "shadow" in the title. The book, you might say, is a phenomenology of those shadows around the globe.

In what way is this book different than your previous ones, and is it at all connected to your series of books you dubbed the "Intifida Trilogy"?

Dabashi: "Europe and its Shadows: Coloniality after Empire" is very much connected to that Intifada series. Such events as the Palestinian Intifada or the Egyptian revolution, or the Arab Spring etc. have a mechanical and an organic dimension to their utterances. In my quick reflections in the form of my Al Jazeera columns I attend mostly to their mechanical aspects. But those who know my work in a more serious way can immediately see that my points are related to more deep-rooted issues in my thinking. In a way I am blessed to be ambidextrous in my writing. But in either hand I hold my writing pen, as it were, it comes from the same critical thinking. There are actually three platforms: Facebook, Al Jazeera, and my books: three slightly different playing fields where I play ball.

"Europe has long imagined itself as the centre of the universe" is the first sentence in the description of your new book. Do you still think that this is the case?

Dabashi: That "Europe" is no longer the centre of anything, let alone the universe. Europe has been systematically and consistently decentred. It can hardly hold itself together let alone be the centre of anything. But the phantom feeling of its idealism still persists apace. I am after dissecting that phantom feeling. As I say somewhere in the book, Europe has been looking down from behind our shoulders when we write anything, and now in this book I look down and in fact stare down to "Europe" as it has written itself. But I do so neither as an outsider nor as an insider but as a traveller through Europe. I have never lived in Europe, but I have travelled extensively from one end to the other of Europe. I am neither angry with Europe nor enthralled with it – the two feelings that distort truth.

With the rise of the far-right populists, in Germany and Europe as a whole, there is a lot of tension. In the recent European Elections, the far-right party AFD used the "Slave Market" by Jean Leon Gerome as a campaign poster, how is this issue addressed in your new book and do you think this development will intensify or change anytime soon? How does this situate in terms of "Post-Orientalism"?

Dabashi: As I have argued before, "Orientalism" is a work in progress, it is an unfolding falsehood. It simply refers to the relation of power and knowledge production. Since that relation of power is amorphous, not ethnocentric nor stable, so does knowledge production commensurate with it and assumes amorphous shapes. Jean Leon Gerome drew with power and confidence. Today European fascists and racists use it with fear and loathing. These are two different moments.

You worked a lot on Edward Said, especially on your book "Post-Orientalism"; can you imagine how he would react to this current development in politics?

Dabashi: He would of course be horrified. But he has left us with a massive body of work that has enabled generations of scholars and critical thinkers to think in his vein. At the end of a magnificent poem, Rumi finally gets tired of saying what he was saying and says to the musicians in the gathering, "well, you get my point, just continue to play along the same lines". It was the same with Said. He discovered a new episteme, and we now get to conjugate it to completion, and perhaps even chance upon the horizons of a new world. That is the reason why his political enemies are still active in the U.S. Department of Education trying, entirely in vain, to erase his memory. But he changed the very DNA of our critical thinking. These puny little minds from Tel Aviv to Washington DC know full well they are desperately swimming against a massive, magnificent torrent.

If you look back at the beginning of the revolutions starting in 2011, and how they unfolded now, would you write some of your articles or books like the "Arab Spring" in a different way today?

Dabashi: No, I would not. As I said early in my book on the Arab Spring, that whole book was my way of joining masses of millions of people from Tahrir square in Cairo, around the globe and shouting "people demand the overthrow of the regime". It was and it remains my "Communist Manifesto" (1848) and I am yet to be convinced that I should write my "The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte" (1852), as it were, with Abdul Fattah al-Sisi standing for Charles-Louis Napoleon Bonaparte.

You are writing regularly for Al Jazeera. How do you choose the topics for your articles and are these a starting point for new ideas which could be expanded into monographs?

Dabashi: I choose them while I am still in bed very early in the morning and reading the news upside down on my iPhone in the dark of the early dawn. I read and write and think and fume or laugh etc. and before I get up I am sometimes down with an entire article. Then I have to polish it and send it to my magnificent editors. Yes, sometimes they point to issues that need more relaxed and expansive reflections that emerge in my books. As I said, it is the same critical thinking playing on slightly different playing fields.

Interview conducted by Tugrul Mende