A naked image of the truth

How is Tehran getting through the coronavirus crisis?

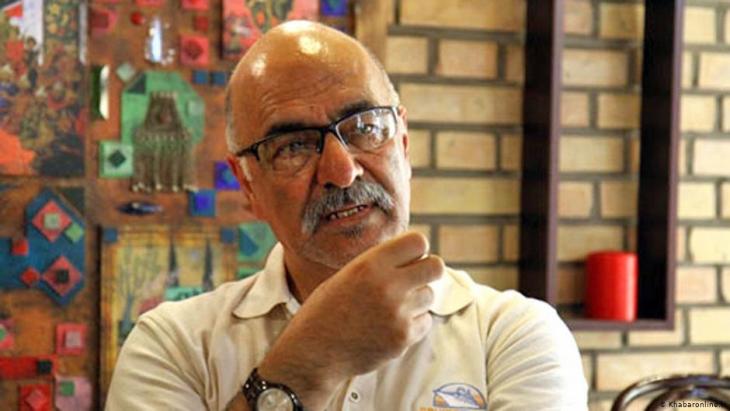

Mahmoud Hosseini Zad: The government confirmed that the pandemic had reached Iran on 19 February. In mid-March, they told us to be careful. Then we learned that the virus had been circulating since the start of January. After China, Iran was the first country where the infection rate rose rapidly. Apparently, a Chinese businessman died of the virus in Iran as early as December. That was a shock. We'd been living with the illness for three months without realising it. The parliamentary elections and the anniversary of the Revolution were both in February, and the government had held back because of them. Shortly before that, I had spent a few weeks on the Caspian Sea. Back in Tehran, it became clear that the first large outbreak had happened there. I've been staying at home ever since.

And there is some doubt about the figures. A daily newspaper was banned just recently for reporting on them...

Hosseini Zad: Yes, the press regulation council banned the paper Jahan-e-Sanat on 11 August, after it published an interview with a member of the National Staff for Combating Coronavirus. The headline was: "Don't trust government statistics". The interview said, among other things, that only a twentieth of the data on the coronavirus situation was accurate.

And are there legal protective measures in place?

Hosseini Zad: There are calls for people to wear masks and keep their distance, and many people do, at least here in north Tehran, where I live. A month ago, they stopped allowing people to go on the metro or the buses without a mask. And you have to wear a mask in government buildings. There are bottles of disinfectant on café tables. On the other hand, the authorities hesitated to bring in a quarantine for a long time when the virus broke out in the sacred city of Ghom, and even now, religious ceremonies are still taking place, despite the pandemic. There was a disagreement back in March over whether the university entrance exams could take place. First they were postponed, but then they were held in August after all. The government is putting forward the economic argument: you can't close everything down...

A complete shutdown could be really fatal for the ailing Iranian economy, couldn't it?

Hosseini Zad: Yes, it would be very dangerous. And there is no state support like the emergency relief you have in Germany. Here, if you don't work, you don't eat. The metros are full, because people have to get to work.

How is the cultural scene dealing with the situation?

Hosseini Zad: Cinemas and theatres have been open again since June, but not many people are going. They tried setting up drive-in cinemas, but without any great success. Culture has largely gone online. Film premieres are being streamed, and there are a lot of online readings.

What about publishers? For a while it was said that they could hardly print any books because paper was so expensive...

Hosseini Zad: That has nothing to do with coronavirus; it's a problem that has been around for a long time. But I've never really understood the politics of publishing in Iran. On the one hand, you hear a lot of publishers moaning that the costs are so high and times are so hard, and they only print a few hundred copies of some books. And on the other, the larger publishing houses also get support from the government. Cheap paper, for instance, or real estate. And the authorities always buy huge quantities of books for libraries. It's more the small publishers who have the problems.

Your translation of the diaries of David Rubinowicz was published recently. David was a Jewish boy who was murdered at just 15 years old in the Treblinka extermination camp. The Tehran Times said you translated the book 40 years ago...

Hosseini Zad: Not long after the Revolution, the Bamberg Germanist Faramarz Behzad and I translated the complete works of Brecht for a major publishing company. Then came the Iran-Iraq war, Brecht was banned, and the project collapsed. The publisher was dispossessed and nationalised. And that was when the poet SAID sent me the Rubinowicz book. The original is in Polish, and I translated it into Persian from the German translation.

The Revolution didn't play out as we imagined; it showed its true face quite quickly. And I found the same thing in Rubinowicz's diaries. They are about life with the fascists. A 12-year-old Jewish boy living in a village in southern Poland writes his diary in a school exercise book, very concise, clear, laconic. He paints a naked image of his truth. The corrupt Germans attack Poles; the Poles betray other Poles; the Jews betray the Jews. That was our society then; that is still our society now. The book is one big plea against fascism.

But because of the whole situation, it couldn't be published, and it stayed in my drawer for decades. Until I gave it to a friend who works as an editor at Saless Publishing House. He wanted to do it, and sent the original off to the authority to which you have to submit all books before publication to get permission to publish. And they decided that everything relating to the murder of Jews had to be cut. That was mainly the passages of commentary by the Polish publisher that supplemented the diary. It isn't the first time something like this has happened to me. I once translated a Fassbinder play, "Just a Slice of Bread". We were told that even the names of the concentration camps had to be cut. But we didn't accept that, and we kept fighting until the authority gave in.

Is there any uncensored literature about the Holocaust in Iran?

Hosseini Zad: Yes, there is. The discrepancy here is interesting: authors are in prison, but you can still buy their books. The censorship authority has certain red lines you can't cross. When it comes to God and Islam, for instance. But there are no real rules. It depends on who is checking a book. One person does it one way, another will do something different. A current example: I translated Dürrenmatt's novel "The Execution of Justice" a little while ago. There's a lawyer in it who is also a pimp. The word "pimp" had to go. "Whore", "hooker", "prostitute" – they were all out. "Sexual intercourse", "rape", "lesbian" and "homosexual" as well.

How do you deal with that?

Hosseini Zad: The authority sends a letter to the publisher detailing what has to be cut completely, and what can be changed. I've reworded a few things. We'll see what they say now. And while all these terms are problematic, the authority has no problem with the fact that the protagonist is an alcoholic and is constantly drinking. In another book, meanwhile, words like "beer" and "whisky" had to be cut.

It sounds very arbitrary...

Hosseini Zad: It depends on the mood of whichever official is reading the book. As a rule, you very rarely have problems with philosophy and non-fiction. Until a few years ago, certain authors and publishers would deliberately include some problematic words on the first few pages so that the officials had something to censor, and then wouldn't look so closely at the later pages. That doesn't work so well nowadays, because they can search for keywords digitally. But you can never tell beforehand exactly what is going to be cut. They are very strict with literature; in films and on stage, you can say and do things that wouldn't be possible in books. At the moment I'm working on a novel of my own, which I fear won't get permission to be published, and so I'm thinking about publication abroad.

Interview conducted by Gerrit Wustmann

© Qantara.de 2020

Translated from the German by Ruth Martin