The Jerulin process

Guy, you lived in Jerusalem for many years and a lot of your art projects have deep connections with the place. What makes the city so interesting for you?

Guy Briller: One of the things that inspired me during my studies of Jerusalem was the mismatch between the promise and the reality. The essence of the word Jerusalem in Hebrew is "One" or "Unity". So the promise of Jerusalem is very strong. In a way it is the strongest and most relevant geographical presence of monotheism in the world. It is one of those places that allows us to think, allows me to think as myself, as one. The root of it is somewhere in the ancient myth of Judaism, then Christianity and then Islam. But the reality is almost the opposite. This dichotomy presented a huge field of action for me, describing trails where you can penetrate the obvious and see what′s beyond.

Can you give a couple of examples of works you realised in reaction to this issue?

Briller: I worked a lot on the line dividing East and West Jerusalem. One of the major outcomes was a project that I called "No-man′s land". I spent some time re-establishing this no-man′s land in Jerusalem and working with a number of fellow artists to create works within it. One project, for instance, was a video installation with seven screens, where you seem to be in a control room observing the actions of the artists in no-man′s land. Then there was the project that I called "Listen", which I started in Jerusalem in 1998. I took a map of the city and added an ear to it. I wanted people to start listening to and exploring what they didn′t already know.

Two years ago you left your home country to live in Berlin. What made you come here?

Briller: At the time, like many things in life, it wasn′t a clear decision. After a few years of very intense artwork, I felt that I needed a different perspective. So I went for a ten-month trip with my family. The idea was to come back, but part of the journey′s horizon was the possibility that we might also find another place to live. Having been in India, Spain and Portugal, our final destination was Berlin. It was the first time I had ever been to Germany, let alone Berlin. Before I landed, I decided that if I didn′t feel comfortable after a few days, I would leave. But something happened and after one week, I said "Wow!" I was amazed by this place. It was just the opposite of what I had feared.

What were your fears about Berlin before coming here?

Briller: I knew nothing. I had no visual understanding of the city and very little knowledge of Germany at all. An Israeli born and bred, I had been confronted most of my life with those twelve years that nobody talks about and I was fed the whole Zionist story. For most of my life, until I came here, I was not interested in the place. I went out of my way to avoid addressing those probing questions about the links between Judaism and German culture.

Now I know why, because diving into this subject while actually being here is far more interesting. I can let myself sink into the subject, in ways that I know I couldn′t in Israel, because of the preconceptions we were raised with.

Was this new perspective the inspiration for the project ″Jerulin″ that you are currently working on?

Briller: In a way, yes. During the year that I was on the road, I planned to say "Ok, I was in Jerusalem for 20 years, let′s do something else". Only when I settled here, did I realise that Jerusalem was destined to be my topic again. Yet I am not there any longer, so how should I go about it? And then intuitively but quite quickly I decided that my art would be on both cities; it will be about "Jerulin". For me, one of the interesting connections between Jerusalem and Berlin is that both cities used to be divided – of course very differently – in East and West, in a very strict and genuine way. This is an aspect that is highly relevant for the reality of both cities, for their self-image and the issues that arise from it. I wanted to explore that thoroughly.

How did the project actually come to life?

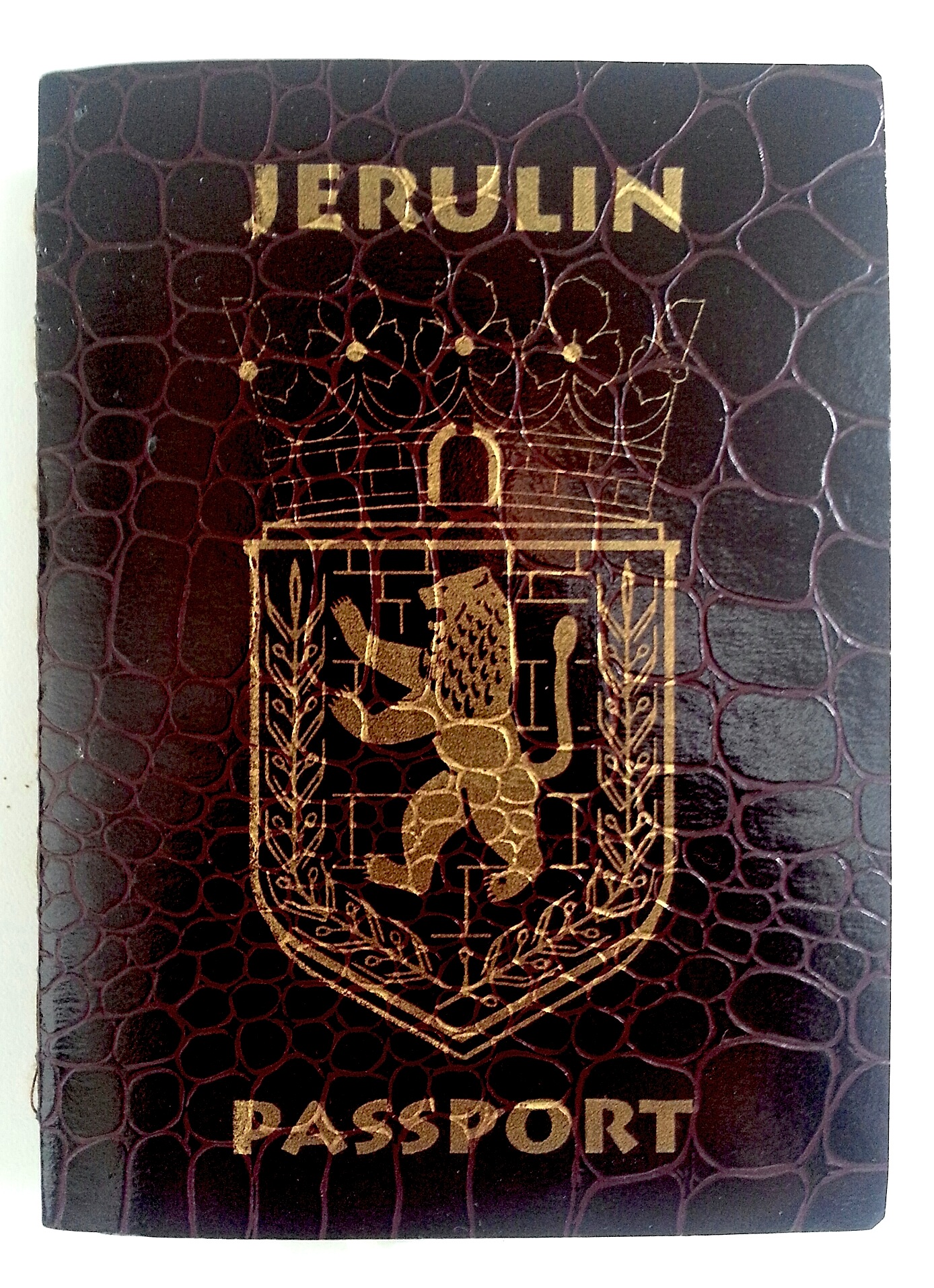

Briller: The very first thing was to decide about the name, that it was "Jerulin" and no other possible combination. The other step was to create a sign that combines the emblems of both cities and therefore create a passport. From then on, I began to believe in it myself, because it suddenly took on a formal existence. I declared my studio the Jerulin embassy, inviting other artists to join me in my research and to reflect with me about the Jerulin process. And I decided to publish this research online on a website, which, in a way, is now the formal location of Jerulin.

Then I began to travel around inside it. The first task was to sort through my works from Jerusalem, trying to figure out what was still of interest to me. Another was travelling around Berlin on a bike, opening my eyes and talking to people to get an idea of where I was. Let me just mention a couple of projects that emerged out of that. One was extending my ear project from Jerusalem to Berlin. The second was working on the no-man′s land, the East-West exploration, once again creating continuity with my work in Jerusalem. And the third was to explore the old Tempelhof airfield, which I feel is a very interesting place in many ways.

Is "Jerulin" only meant to be presented on your website, or do you exhibit the work in galleries as well?

Briller: The first year of this project – Chapter A – was summed up in an exhibition: one was in Haifa at Beit Hagefen, the only serious Jewish-Arab cultural centre in Israel, and the other one was in the headquarter of the Heinrich-Boll Stiftung in Berlin, together with an event to celebrate 50 years of diplomatic ties between Israel and Germany.

The exhibition was called "Some evidence for the short life and death of Alter-J in Jerulin". As you may imagine, Alter-J may be regarded as the alter ego of the researcher, the artist, who is sharing some of the evidence he has found.

New refugees from the Middle East are currently arriving in Berlin every single day. How does this relate to your work?

Briller: I find it interesting that this influx is bringing with it challenges associated with the East-West conflict in Jerusalem. The weight of these questions, the weight of this conflict is suddenly emerging here: it′s as if colonialism is pushing back, forcing people here to think. For me, it means realising that the issues I left behind me, with the aim of meditating about them in a "quiet European manner", are now being challenged by a new rough reality. It′s a tragic kind of colonialism in reverse. It makes the subjects I address in Jerulin more relevant, not only for me as a foreign artist, but also for the audience. It is not a distant past anymore, no window onto some faraway world, it is an actual present reality to be faced right here.

Felix Koltermann

© Qantara.de 2015